Every October, THNOC resurrects its Halloween-themed tour of the Louisiana History Galleries, Danse Macabre: The Nightmare of History. The tour examines the famous haunted legends of New Orleans, as well as some more obscure figures (like the ones shared here) whose lives illuminate darker aspects of the city’s history.

1. Louis Congo—The Founding Era, 1718–1762

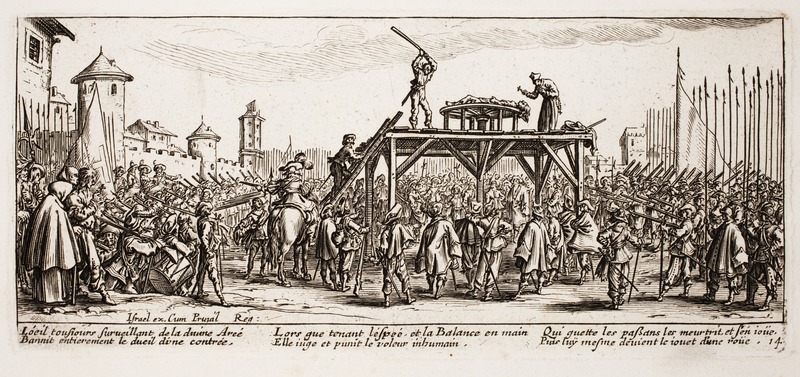

An 18th-century illustration depicts “breaking on the wheel,” a process in which a condemned prisoner was strapped to a wagon wheel to have their bones broken one-by-one with a cudgel. This was the most common means of capital punishment in colonial Louisiana. (Image courtesy the Peace Palace Library).

French Colonial New Orleans was an unruly powder keg of aspiring planters, indentured servants, soldiers, forced migrants from Europe, enslaved Africans, and indigenous peoples of diverse nations. Law and order were paramount to colonial authorities.

French Colonial New Orleans was an unruly powder keg of aspiring planters, indentured servants, soldiers, forced migrants from Europe, enslaved Africans, and indigenous peoples of diverse nations. Law and order were paramount to colonial authorities.

Following the example of other French colonies in the New World, in 1725 Louisiana officials gave an enslaved African the impossible choice to remain enslaved or to serve as public executioner. Known as Louis Congo (“Louis” for Louisiana and “Congo” for his place of birth), he was given his freedom, a plot of land, and rations of food and wine in exchange for his services. He also earned a fee for each punishment meted out.

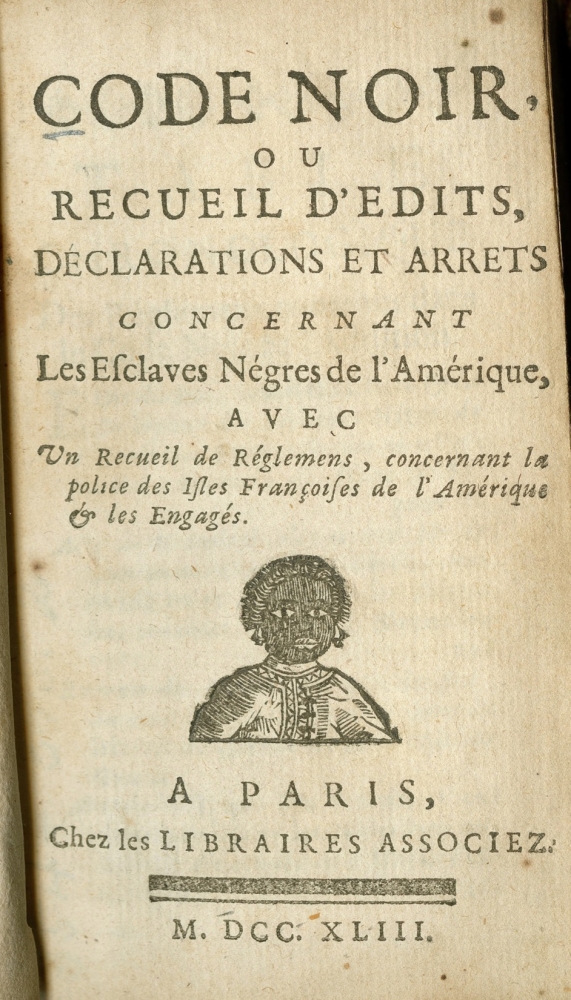

Serving for at least 12 years, Congo was the sole man in New Orleans with the authority to carry out whippings, hangings, and worse, against residents of all races. A common punishment for Frenchmen accused of thievery, smuggling, or desertion was branding with the fleur-de-lis. Enslaved individuals accused of running away were punished according to laws set out by the Code noir (right), which stipulated branding, hamstringing (crippling a person so he cannot walk by cutting the tendons in the back of the leg), amputation of ears, and, upon the third offense, death. The preferred method of capital punishment, regardless of race, was breaking on the wheel. The condemned was strapped to a wagon wheel, his bones were broken one by one with an iron cudgel, and he was left to die.

2. Père Dagobert—The Spanish Dominion, 1762–1803

Legend has it that Père Dagobert dragged the bodies of French insurrectionists for a proper Catholic burial at St. Peter Street Cemetery. Building on Pirates Alley (detail); Between 1929 and 1940; glass negative by Daniel Sweeny Leyrer, photographer; THNOC, gift of Allan Phillip Jaffe, 1981.324.1.34

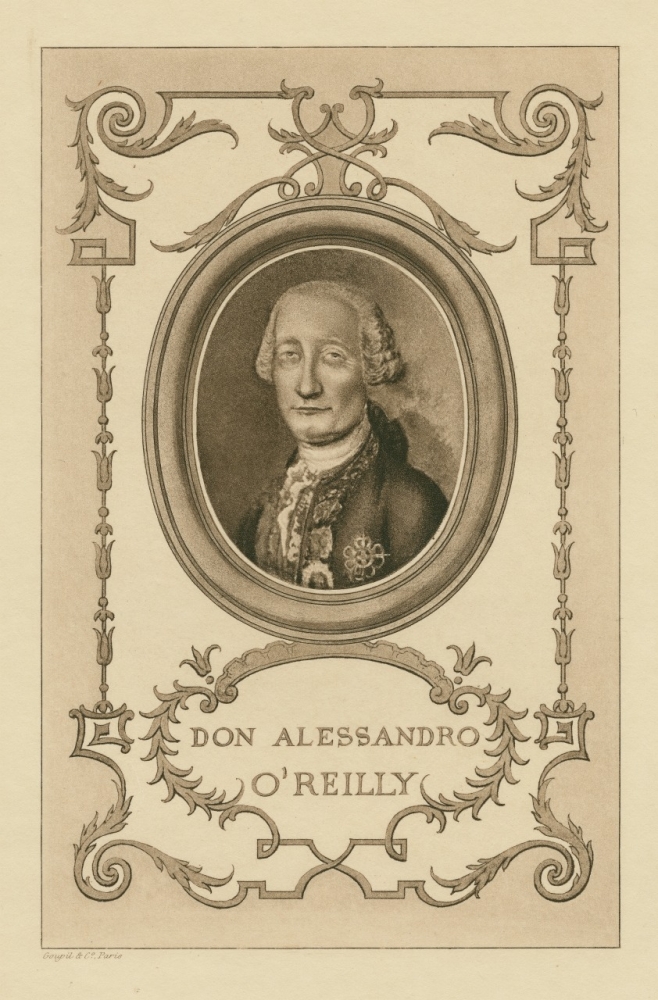

In 1762, during the Seven Years' War, France ceded Louisiana to its Bourbon ally Spain in the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau. When French colonists in New Orleans received the news, few were pleased. Fearing Spanish trade restrictions would ruin the local economy, a rebellion of urban elites and rural militias expelled the first Spanish governor, Antonio de Ulloa, in 1768. The following year Spain sent military governor Alejandro O’Reilly (right) with a flotilla of 23 armed ships, to restore Spanish authority in New Orleans. O’Reilly had five of the leading conspirators executed at Fort St. Charles, at the foot of present-day Esplanade Avenue and Frenchmen Street (named by Bernard de Marigny in honor of these French rebels).

In 1762, during the Seven Years' War, France ceded Louisiana to its Bourbon ally Spain in the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau. When French colonists in New Orleans received the news, few were pleased. Fearing Spanish trade restrictions would ruin the local economy, a rebellion of urban elites and rural militias expelled the first Spanish governor, Antonio de Ulloa, in 1768. The following year Spain sent military governor Alejandro O’Reilly (right) with a flotilla of 23 armed ships, to restore Spanish authority in New Orleans. O’Reilly had five of the leading conspirators executed at Fort St. Charles, at the foot of present-day Esplanade Avenue and Frenchmen Street (named by Bernard de Marigny in honor of these French rebels).

According to legend, the men were denied traditional Catholic burial rites by the cruel O’Reilly. Their devastated families solicited the aid of the priest of St. Louis Church, Père Dagobert de Longuory, who miraculously eluded the Spanish guard in the dead of night and transported the bodies for interment at the St. Peter Street Cemetery.

On certain foggy mornings in the alleyways of St Louis Cathedral, one may catch a scrap of song and the sandaled footsteps of the singing Capuchin, as he repeats his miracle procession.

3. Jose “Pepe” Llulla—The Age of Chivalry, 1820–1865

A traditional duel with swords is fought on the Dueling Grounds in City Park. The Old Dueling Grounds in City Park, Showing the De Lissue-Le Bouisque Duel in 1841, New Orleans, La. (detail); between 1890 and 1950; postcard by Curt Teich and Company, Inc., publishers; THNOC, 1975.85.10

The classical duel once enjoyed a passionate following in New Orleans. Slights of honor were met with the challenge, and settled in blood. To refuse was unbecoming of a gentleman. Creole duels, fought by the sword and concluded with the first draw of blood, were generally nonfatal. Preeminent amongst New Orleans swordsmen was the Spaniard Jose “Pepe” Llulla, who owned a fencing school at Exchange Alley in the French Quarter. Born on the Mediterranean island of Menorca in 1815, Llulla pursued a seafaring life as a young man. He worked the route between New Orleans and Havana, before eventually settling permanently in New Orleans.

The classical duel once enjoyed a passionate following in New Orleans. Slights of honor were met with the challenge, and settled in blood. To refuse was unbecoming of a gentleman. Creole duels, fought by the sword and concluded with the first draw of blood, were generally nonfatal. Preeminent amongst New Orleans swordsmen was the Spaniard Jose “Pepe” Llulla, who owned a fencing school at Exchange Alley in the French Quarter. Born on the Mediterranean island of Menorca in 1815, Llulla pursued a seafaring life as a young man. He worked the route between New Orleans and Havana, before eventually settling permanently in New Orleans.

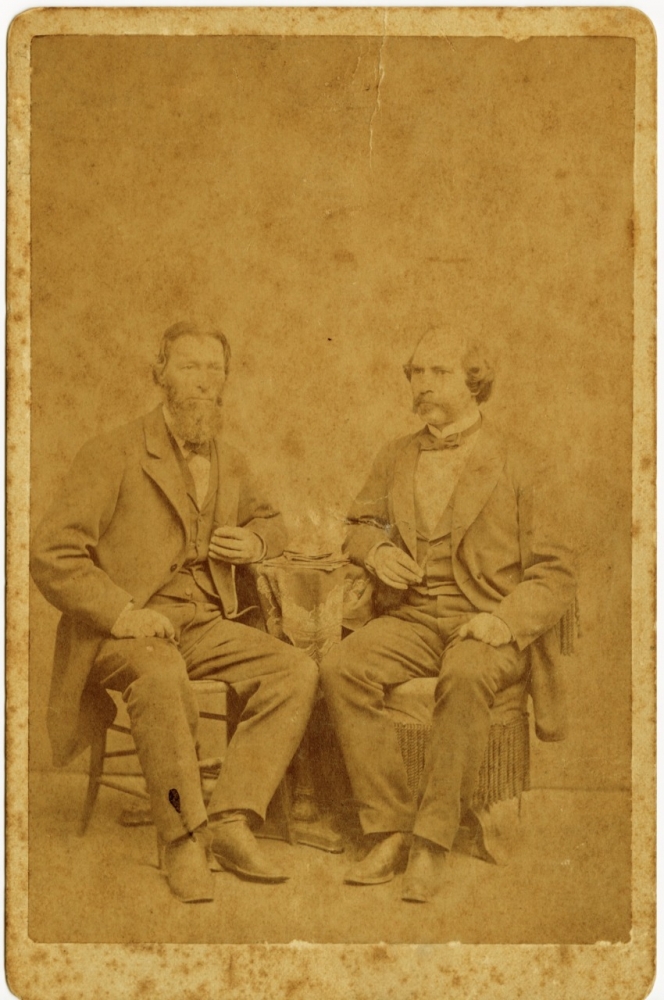

Llulla (seated on the left in the image to the left) participated in approximately 20 affairs of the sword and served as “second” (the primary duelist’s adviser and confidant) in dozens more. Renowned for his fighting skill, Llulla found success in diverse business ventures; he organized bull fights in Algiers and owned a bar, land on Grande Terre Island in Barataria Bay, and St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street in the Upper Ninth Ward. A legendary duelist owning a cemetery led to rumors that a section of the graveyard was reserved for his victims. However, Llulla is believed to have only ever killed two individuals in his duels. Many of his challengers, in fact, bowed out before the moment of truth.

Pepe’s intense loyalty to Spain proved to be the very cause of many of his conflicts. Home to a large community of Latin American exiles in the mid-19th century, New Orleans was also a hotbed of anti-Spanish subversion, in particular supporters of Cuban independence from Spain. Following a failed expedition from New Orleans to Cuba in 1851 that resulted in the deaths of many American citizens, violent mobs gathered outside the Spanish consulate and raided Spanish-owned businesses. In the aftermath Llulla issued a public challenge to all Cuban revolutionaries residing in New Orleans. For his defense of the honor of the Spanish crown, Llulla was made a knight of the Order of Charles III.

4. Doctor John—The Eternal Realm, late 19th century

John Montanet worked on wharves in New Orleans where he could purportedly tell the future by reading markings on bales of cotton. The Levee - New Orleans.; 1884; lithograph by Currier and Ives, publisher, after William Aiken Walker, painter; THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1941.1

Doctor John Montanet was a singular force in the spiritual world of 19th-century New Orleans. A contemporary of the Voodoo queen Marie Laveau, Montanet was born in Senegal in the early 1800s. According to folklorist Lafcadio Hearn, he was kidnapped at a young age by Spanish slavers and sold in Cuba. He was taught to cook and eventually granted freedom, after which he took a job in the galley of a Spanish vessel. Montanet left the ship at New Orleans and found work on the wharves as a cotton-roller. Among his coworkers he developed a reputation as a fortune teller, being able to tell the future by the markings on bales of cotton. Blacks and some whites paid him to prophesy for them.

Doctor John Montanet was a singular force in the spiritual world of 19th-century New Orleans. A contemporary of the Voodoo queen Marie Laveau, Montanet was born in Senegal in the early 1800s. According to folklorist Lafcadio Hearn, he was kidnapped at a young age by Spanish slavers and sold in Cuba. He was taught to cook and eventually granted freedom, after which he took a job in the galley of a Spanish vessel. Montanet left the ship at New Orleans and found work on the wharves as a cotton-roller. Among his coworkers he developed a reputation as a fortune teller, being able to tell the future by the markings on bales of cotton. Blacks and some whites paid him to prophesy for them.

After a few years Montanet had amassed sufficient wealth to purchase property along Bayou Road on the block bounded by Prieur and Roman Streets. He practiced herbal medicine and occult arts in addition to fortune telling. He charged high fees for various potions and herbs, charms, consultations, hair tonics, lottery advice, and other notions.

Lafcadio Hearn offers a colorful picture of the Doctor—called such because of his knowledge of the occult—at the height of his powers: “About his person he always carried two small bones wrapped around with a black string, which bones he really appeared to revere as fetishes … He had his carriage and pair, worthy of a planter, and his blooded saddle-horse, which he rode well, attired in a gaudy Spanish costume, and seated upon an elaborately decorated Mexican saddle.”

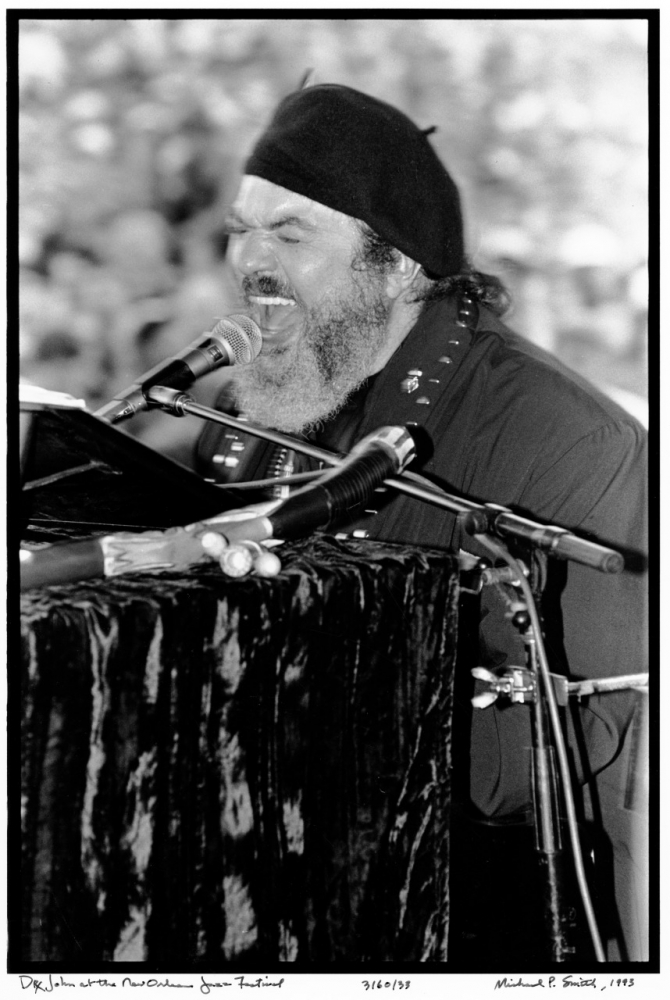

Mac Rebennack (right) took his stage name, Dr. John the Nite Tripper, in respect of this illustrious New Orleanian.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.