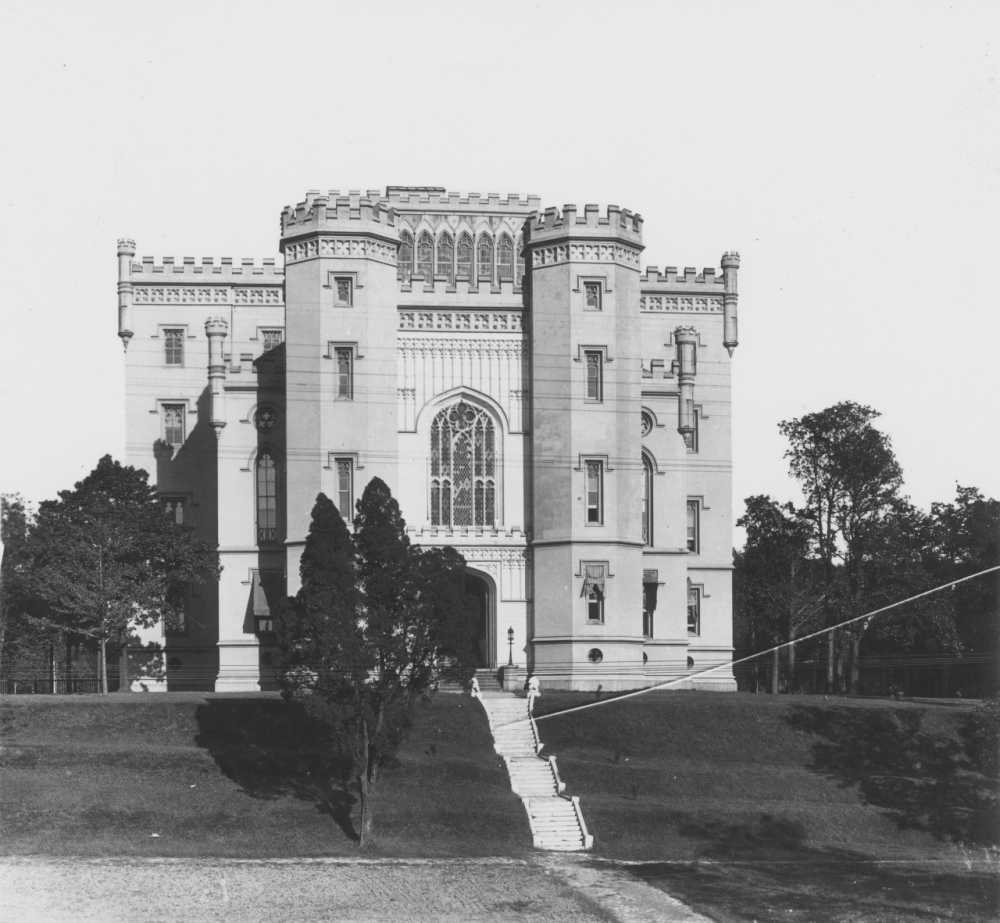

In the 1850s, the Louisiana State House was likely the first landmark that riverboat travelers spied as they approached Baton Rouge. Hexagonal turrets, crenellated moldings, and a light exterior made the Gothic Revival capitol building a veritable riverfront castle. Architect James H. Dakin specifically chose this dramatic style to make Louisiana’s capitol building unique among the plethora of Greek Revival columned state houses elsewhere. (The Connecticut State Capitol, designed by Richard Upjohn two decades after Louisiana’s, is the nation’s only other Gothic state house standing today.) Today visitors can still marvel at the structure, which now functions as a museum called the Louisiana Old State Capitol.

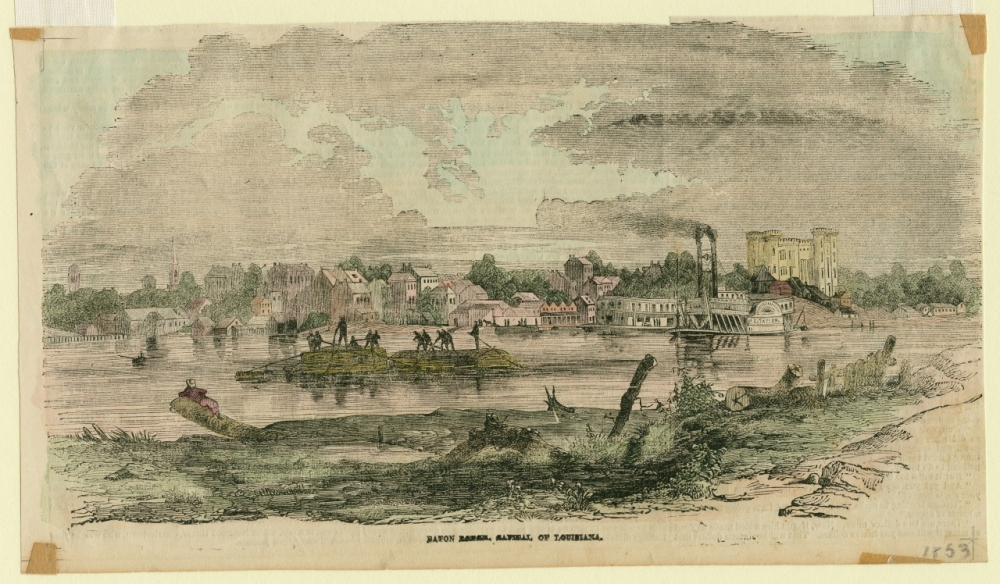

An 1853 newspaper clipping with a view of the Baton Rouge skyline from across the Mississippi River shows the Old State Capitol visible at right. (THNOC, 1974.25.30.148)

Not every traveler enjoyed the view, though. In Mark Twain’s 1883 memoir, Life on the Mississippi, he famously critiqued the “whitewashed castle” as an “architectural falsehood.” He laid the blame for this “ungenuine” structure on a specific person:

Sir Walter Scott is probably responsible for the Capitol building; for it is not conceivable that this little sham castle would ever have been built if he had not run the people mad, a couple of generations ago, with his medieval romances. The South has not yet recovered from the debilitating influence of his books.

The Old State Capitol as it appeared around 1932. (THNOC, 1979.89.7266)

Beginning with the enduringly popular Ivanhoe, Sir Walter Scott authored multiple bestselling medieval historical fiction novels between 1819 and his death in 1832. Fifty years later, Mark Twain saw Scott’s Romantic adventures as opponents of modern progress. To him, the South’s juvenile attachment to Scott’s novels caused a “maudlin Middle-Age romanticism” obsessed with outdated honor duels, flowery language, and empty titles of rank. Twain even suggested that this “Sir Walter disease” contributed to the Civil War. He much preferred the “wholesome and practical 19th-century smell of cotton-factories and locomotives.”

Mark Twain wasn’t wrong that northern states had a more industrial economy, but his pithy portrait of a uniquely medieval South was an oversimplification. Louisiana’s “sham castles” and Gothic cathedrals were part of a nationwide trend. In fact, the neo-Gothic architecture Twain despised was largely a northern import.

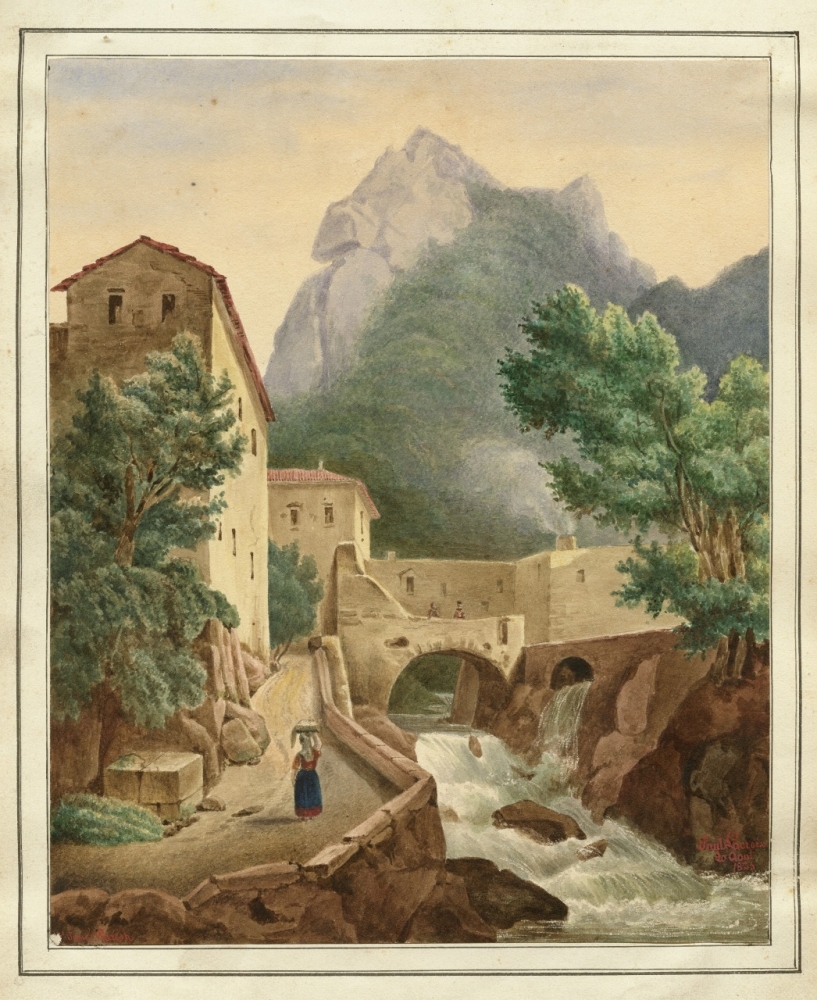

This 1830 watercolor landscape is by Paul Lacroix (ca. 1811–1847). Born in France, Lacroix lived in New Orleans from around 1835 to his death in 1847. He frequently painted Romantic landscapes like this one during his travels in Europe and the Americas. (THNOC, 1962.1.8.2)

The Gothic Revival became popular across Europe and the United States during the 1830s and ’40s. Weary from decades of revolutions and Napoleonic wars, design culture turned from the authoritative geometry of Greek Revival and Empire styles to the softer, wilder Romantic aesthetic. Poets and painters imagined emotional scenes in overgrown forests and ruined castles. With continental travel no longer dangerous, wealthy American tourists could embark on a Grand Tour to see Europe’s medieval landscapes in person.

As with trends today, people imitated innovative styles demonstrated by celebrity influencers. English author and politician Horace Walpole designed his London villa Strawberry Hill as a “little Gothic castle” showplace. Sir Walter Scott followed suit with his own miniature castle, Abbotsford, in Scotland.

In the United States, high-profile Gothic style buildings in northern cities inspired imitators elsewhere. New York University specifically commissioned a Gothic-style main building in 1833. This kicked off the Collegiate Gothic style that remains synonymous with university campuses to this day. Likewise, when Trinity Church Wall Street opened the third generation of their downtown building in 1846, its spire made it the tallest building in the United States. Architect Richard Upjohn’s design featured stone walls, ribbed vaults, and abundant pointed arches. New Orleans added its own Gothic churches, such as St. Patrick’s in 1837 and First Presbyterian in 1857, both near Lafayette Square.

Left: Transverse Section of St. Patrick’s Church; 1834–51. (THNOC, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Kenneth McLeod Jr. in memory of the Gallier and Capdevielle families, 2008.0087.86)

Right: Old First Presbyterian Church; 1918–38. The church suffered severe hurricane damage in 1915 and was demolished in 1938 to make way for a federal government office building. (THNOC, 1973.61)

Gothic Revival architecture was well-suited for larger public spaces like churches, schools, steamboats, and even shopping districts. Merchants along Canal and Tchoupitoulas added ornate cast-iron Gothic decorations to their storefronts. D. H. Holmes’s four-story department store built in 1849 impressed customers with its marble Elizabethan Gothic exterior, interior archways, and glass dome skylights. Perhaps the most monumental Gothic building in New Orleans was the massive Touro Alms House, funded by an 1854 bequest by philanthropist Judah Touro. William Alfred Freret Jr.’s massive three-story design stretched between Piety and Desire Streets in the Bywater neighborhood. Unfortunately, the building did not last long; it was destroyed by a kitchen fire at the end of the Civil War.

Interior of the D. H. Holmes dry goods store on Canal Street around 1885. (THNOC, 2012.0208.2.373)

The Gothic craze was not limited to large public buildings. Books by American architects and designers made European style even more accessible for consumers. Particularly influential were New Yorker Andrew Jackson Downing’s Cottage Residences (1842) and Architecture of Country Houses (1851), which showed how to create a cozy Gothic residence that sat in harmony with the landscape. Rural Architecture, published by Richard Upjohn in 1852, offered Carpenter Gothic church designs that small communities could construct with just wooden beams. New technology like the steam-powered scroll saw mass-produced decorative elements like delicate Gothic tracery moldings for Americans to add to their homes.

1850s editions of Andrew Jackson Downing’s Cottage Residences and Architecture of Country Houses, owned by a resident of Shadows-on-the-Teche plantation in New Iberia, LA. (DAGS Database: DAGS-2022-0009, -0010)

Left: These hall chairs and étagère were made of oak, marble, and glass in either New Orleans or New York between 1851 and 1857. They are part of a private collection in Natchez, MS. (DAGS Database: CIS-2014-0018, CIS-2014-0019).

Right: This harp with intricate, Romantic detailing was made in England between 1830 and 1860. Its owner lived at Rosalie Mansion, a plantation in Natchez, MS. (DAGS Database: CIS-2017-0106)

Rarely did Louisianans outfit their whole house or even an entire room in floor-to-ceiling Gothic. Instead, it was just one of many historically inspired options alongside revivals of rococo, ancient Greek, or even ancient Egyptian décor. Fully Gothic cottages like Afton Villa in West Feliciana Parish remained an unusual sight. New York–trained James H. Dakin deliberately chose a unique Gothic look for his Louisiana State House design, but it was a standout in his career full of Greek Revival buildings.

Practical considerations likely kept the Gothic Revival style from taking over the Gulf South. Unlike in New York or Connecticut, Louisiana did not share medieval England’s cool climate and local sources of stone. Builders in the New Orleans area typically relied on brick covered in stucco to combat the heat and humidity. Southerners also favored Creole raised basements and long outdoor balconies to help circulate cooler air. The most heavily decorated columned porches, like the facade of San Francisco plantation in St. John the Baptist Parish, are sometimes called Steamboat Gothic style.

Left: Afton Villa as it appeared around 1960. (THNOC, gift of Jeri Gustafsson, 2017.0153.1)

Right: San Francisco plantation in July 2021. (Photograph by Sarah Duggan)

For white middle-class northerners, the foreignness of southern landscapes and climate became marketing features after the Civil War. Travel guides like Appletons’ drew tourists with extra cash to experience the “weird,” “grotesque,” and “sublime” swamps of the Deep South. Spanish moss draped on tree limbs overhead could even evoke the vaulted ceilings of a Gothic cathedral. Plantation buildings damaged in wartime contributed to the atmosphere of eerie decay. Lacking any real medieval castles, the remains of forced-labor farms overseen by enslavers with feudal powers were the closest these Americans could get to ancient ruins. Touring this exotic fallen civilization reinforced tourists’ sense of superiority—the South was an aberration consigned to history, while the North represented America’s future.

An invitation to the Krewe of Rex’s 1881 Mardi Gras ball. The theme was “Arabian Nights Tales.” (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1960.14.73)

Which brings us back to riverboat traveler Mark Twain and his distaste for southern “sham” civilization. He especially despised the flowery royal titles of Mardi Gras krewes. “The very feature that keeps [Mardi Gras] alive in the South—girly-girly romance—would kill it in the North or in London.” If he had visited Louisiana more often, he would have learned that Carnival costumes were more than just medieval. Just like their northern neighbors, New Orleans elites craved a getaway to the exotic past, however stereotypical or problematic. Mardi Gras parade themes of the 1880s featured exotic past civilizations, real and legendary, that krewes could gloat over outliving: “The Aztecs,” “Arabian Nights Tales,” “Atlantis: The Antediluvian World,” and “Ancient Egyptian Theology.” Perhaps they weren’t so different from a Connecticut Yankee like Mark Twain after all.