To the outside world, catching beads at New Orleans Mardi Gras is a euphemism for public indecency. But, as any New Orleanian knows, you don’t have to do anything special to get beads during Carnival. Just stand in one place along the parade route during the two weeks before Fat Tuesday and you will likely get hit in the head with plastic beads, stuffed animals, or light-up necklaces. These “throws,” tossed from riders in the numerous float parades, range from cheap, generic beads to more desirable items such as plastic cups, doubloons, or unique works of art.

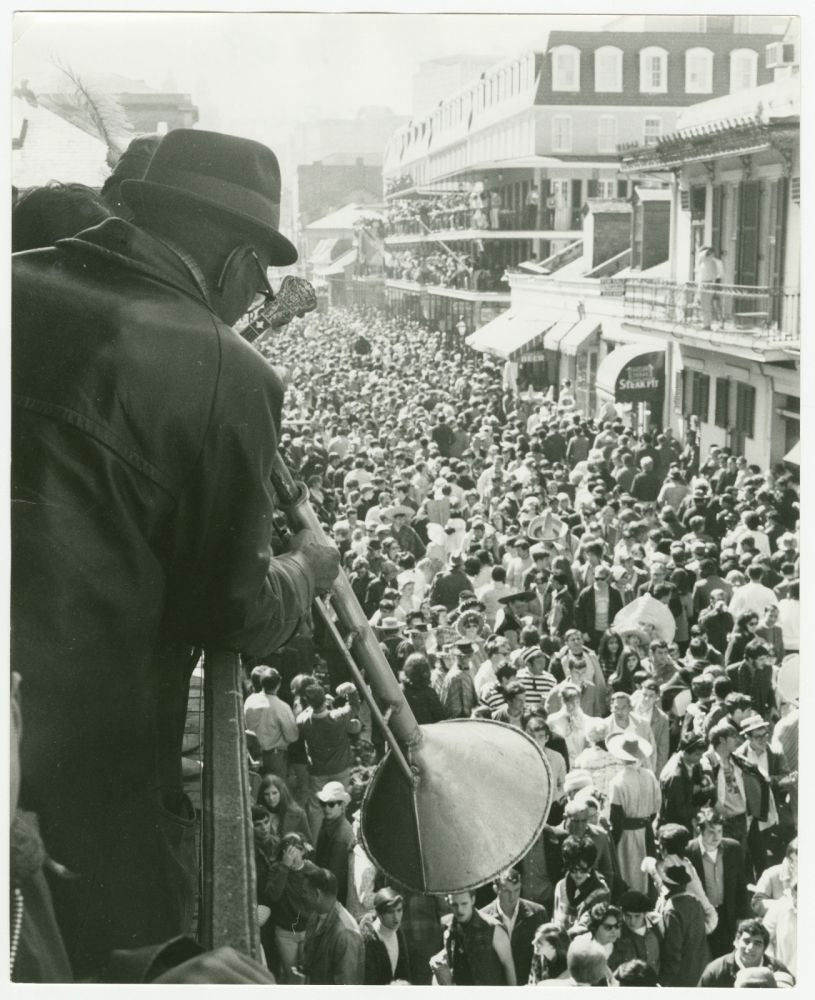

This 1969 image shows a Mardi Gras crowd on Bourbon Street, a locale often associated with the storied phenomenon of "flashing"—baring breasts in exchange for beads—though as any local will tell you, it's a lecherous canard perpetuated by tourists off the parade route. Locals know that such theatrics are far from necessary when it comes to catching Mardi Gras throws. (The William Russell Jazz Collection at THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.331.2336)

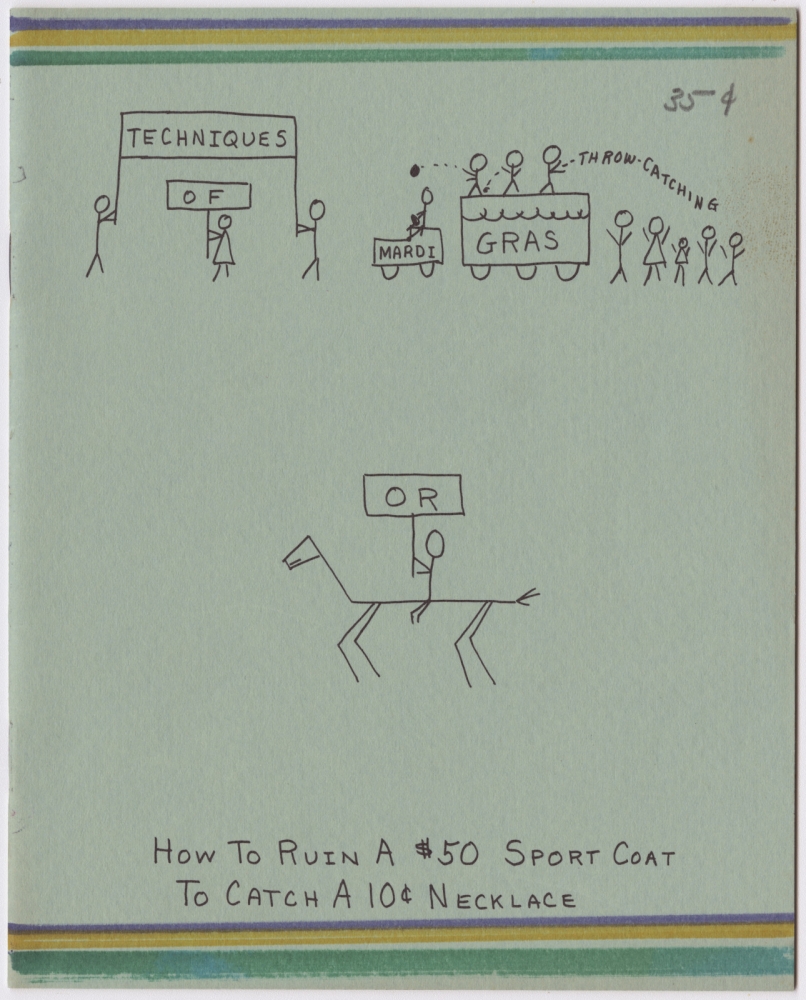

There are ways, however, to improve your chances and ensure a plentiful parade experience. Every local has their own strategy, developed from a season or a lifetime of parade participation. There are disagreements on whether the Uptown route or Canal Street is better, whether to stand on the neutral-ground or sidewalk side of the parade, and the ethics of using signs and nets to catch the attention of parade riders. A few Carnival die-hards have even published their advice, as Vincent Spear did with his 1969 pamphlet, “Techniques of Mardi Gras Throw-Catching; or, How to Ruin a $50 Sport Coat to Catch a 10¢ Necklace.”

Mardi Gras beads on the left are akin to what author Vincent Spear would have been catching at the time he wrote his pamphlet. On the right, a Muses shoe is among the prized throws of modern-day Mardi Gras. (THNOC, gift of Jeffrey Faughnan and Bill Rosenbaun, 2019.0096.69.6; THNOC, gift of Elizabeth Black, 2019.0258)

“This treatise is written to aid the uninitiated in the detection, pursuit and acquisition of Carnival throws dispensed from floats, trucks, cars or horses during a parade,” the pamphlet reads. “Other information of a nature calculated to increase overall enjoyment of the Mardi Gras season is also presented, but the primary objective is to improve the competitive position of the reader when that first float-rider cocks his arm, and the chorus of, ‘Throw me somethin’, mister!’ begins.”

Spear’s treatise includes a simple cover drawing and the sardonic subtitle "How to Ruin a $50 Sport Coat to Catch a 10¢ Necklace." (THNOC, gift of James L. Griffin, 94-230-RL.13)

Beneath the hand-drawn cover, Spear lists his qualifications for authoring the treatise:

Flat fingers—acquired by being stepped on by thousands of unknown heels

Fallen arches and stooped shoulders—acquired by holding one or more children aloft “just until the next float passes.”

Furtive, darting eyes—acquired by trying to gauge opposition in pursuit of potential doubloon held aloft by rider (who then waits until the next block to throw it)

Elongated arms—acquired by grabbing for a flying necklace two feet higher than the good Lord ever intended him to grab

A chronic kidney condition—acquired by a combination of cold weather, daylong lack of sanitary facilities and five cans of beer

Spear’s recommendations focus on where to stand, who to be with, how to catch, and Carnival etiquette, taking into account planning, chance, and unlucky situations.

Where to stand along the parade route

The Rex Bandwagon makes its way down Canal Street in the 1950s or ’60s. Spear liked Canal Street for its sentimental connection to Mardi Gras but argued that the St. Charles Avenue route was the preferred thoroughfare for catching throws. (THNOC, gift of the School of Design, 1977.38.90)

One possible parade-viewing location is along Canal Street, which divides the Central Business District from the French Quarter. While this may be a sentimental favorite, Spear doesn’t recommend it if your intent is to catch copious throws.

Spear’s second option, he writes, is the house of a favorite aunt and uncle, located along the parade route (no judgment on “the fact that Aunt Susie and Uncle Jerome become favorites only at Carnival time”). This location is ideal for the availability of toilet facilities, parking, and a family reunion, but Spear declares that unless it has a balcony or is in the Quarter, it's not the best for throw-catching.

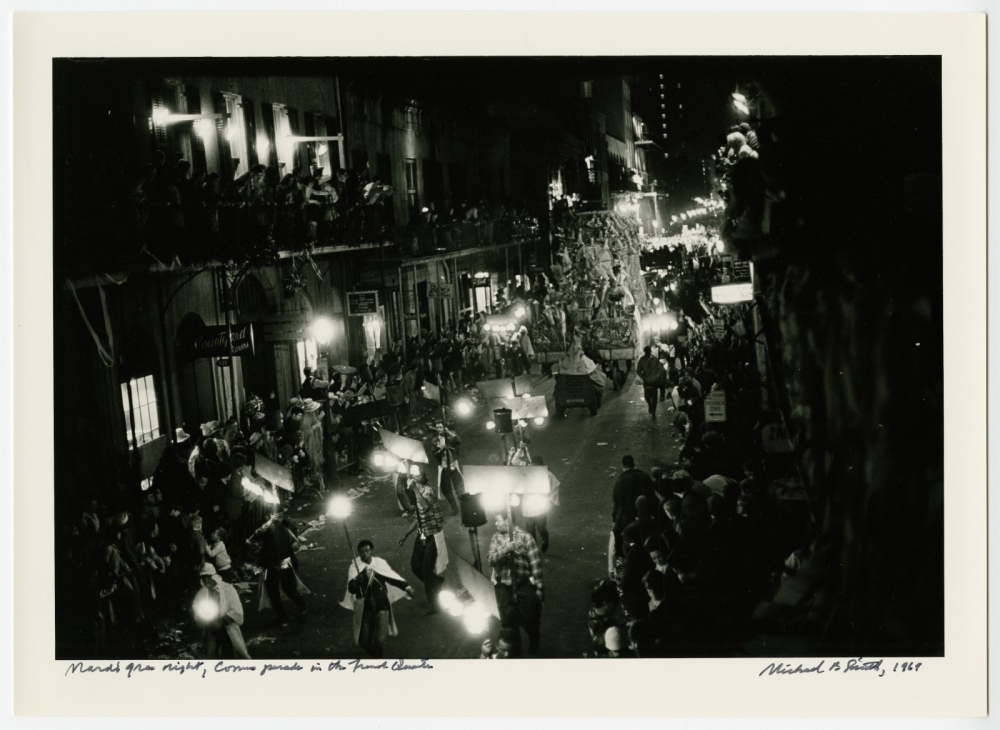

In this regard for the Quarter, Spear’s advice is a little outdated to modern parade spectators. In 1969, 33 float parades took place throughout New Orleans during the Carnival season. They rolled on various routes, through neighborhood streets and thoroughfares in disparate parts of the city. Some of the routes in 1969 went through the narrow streets of the French Quarter, a practice banned in 1973. It wasn’t until after Hurricane Katrina that most Mardi Gras parade routes were consolidated to the St. Charles Avenue route that remains in place today.

Other locations for plentiful throw-catching, Spear says, include the beginning of the parade route, where riders are “fresh and exuberant”; near the Queen’s stand or former Kings’ homes; by a TV truck; on any raised area; or at the end of the route, where krewe members get rid of their remaining throws. Spear notes that you might have the best success standing directly under a balcony that’s just a little too high for an accurate throw.

Where to stand in the crowd

Ladders with seat boxes, like this one from the 1980s, are a common sight along parade routes, elevating children above the scrum for throws. (THNOC, gift of George Schindler, 2018.0247)

Spear discusses the merits of standing at the front of the crowd (easy to lift child up) or the back of the crowd (“more freedom to move”). His strongest advice is not to stand under a streetlight during a night parade, where you could be blinded while looking up for throws.

Spear also provides advice on whether to stand on the right- or left-hand side of the parade route. His analysis, he writes, depends on the ambidexterity of float riders and the likely direction of their throws. Parades were smaller in 1969 than they are today, with only a handful of krewe members riding in the middle of each float. Bacchus, the first so-called superkrewe, had its first parade that year, with 20 riders on each of its 15 floats. In the following decades, floats got larger and larger, sporting riders on all sides, stacked on double decks, and linked on tandem platforms. Today, the argument is between the “sidewalk side” or the “neutral ground side” (the neutral ground being the local term for a grassy median). There is more space on the neutral ground side for larger family parties, while the compact nature of the sidewalk side might lead to a greater density of throws. This curator prefers the sidewalk side, despite the risk of getting swiped by a passing trombone.

Who to stand by and who not to stand by

A crowd at Zulu stretches their hands into the air to catch throws in this 1980 image. (THNOC, gift of Mitchel Osborne, 2007.0001.234)

According to Spear, one should stand by “short people . . . old people . . . women with children who are poor catchers.”

Don’t stand by: All-American basketball centers (or other unusually tall people) or parents with children on ladders. Most important, says Spear, is to not stand near “a pretty girl on a ladder, with a male escort to catch the throws—an unbeatable combination. Will get at least one throw from 90 percent of the riders, thereby depleting potential revenue for surrounding area.”

What to shout

The Krewe of Comus parades through the French Quarter in this 1969 image. Large parades were banned from rolling through the neighborhood in 1973 due to fire concerns. (photograph by Michael P. Smith, © THNOC, 2007.0103.2.362)

While it is not necessary to call for throws, it is hard not to get swept up in the excitement. All along the route people are shouting, singing, chanting, and yelling to each other. The traditional call is, “Throw me somethin’, mister!” Spear notes that the phrase is “not really all that effective, but you can hardly consider you’ve been to the parade if you don’t yell it at least once for each float.”

The final sections of Spear’s treatise cover parade etiquette: what to do for a mutual catch, parking, and the ethics of buying beads prior to the parade and surreptitiously dropping them above a child to ensure the kid catches something (this is unnecessary with modern parade-throw volumes).

“If you are tall, athletic, young, and have a ladder, a pretty girl and an Aunt Susie living next door to the parade Queen’s stand, you shouldn’t have much trouble catching a lot of throws,” Spear concludes. “If you are missing all or most of these factors, this booklet should help you. Come to think of it, if you are tall, athletic, young and have a pretty girl, a ladder and an Aunt Susie living next door to the Parade Queen’s stand, do you really need the ladder and Aunt Susie to have a good time at Mardi Gras?”

Updates for the 21st century

The author is pictured with an unknown baby—kidding, that’s her baby!—at Mardi Gras 2020.

If you’d like the advice of a novice parade enthusiast (not born in New Orleans), here are this author's seven personal parade tips:

1. Stand on the sidewalk side with friends and on the neutral ground with family.

2. Keep your head and arms up to catch throws and to protect yourself. A bag of beads to the face hurts!

3. If you use a ladder for children (a great way to keep them safe above the crowd), make sure it is six feet from the street, and have an adult spotter standing behind the kids to help catch and/or swat away incoming projectiles.

4. NEVER pick beads up off the ground. You WILL catch some eventually.

5. Be prepared: bring food, drink, and sunscreen for the day. Wear comfortable clothing and closed-toed shoes. Know where your bathroom is.

6. If you know someone riding in the parade, find out their position ahead of time so that you can call out to them on the route. This is the best way to get a Muses shoe.

7. Have lots of fun! Grab as many throws as you want and recycle them when the season is over.