Two days before Hurricane Ida made landfall in Louisiana, University of South Carolina climatologist Cary Mock tweeted an ominous warning: “Ida may rival my 1812 hurricane.”

Back in June 2021, we published a story about the 1812 storm, which Mock pegs as a Category 4 on today’s Saffir-Simpson scale. Mock described the 1812 hurricane as a worst-case scenario for New Orleans, with severe winds and converging tides of floodwater from the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain. Taking stock of current climate conditions, Mock warned in June that similar devastation could happen again.

Ida may rival my 1812 Hurricane (which I think is a category 4, and I am more confident today than when I published my paper years ago, since I have more data). We shall see. #Ida #Hurricane #hurricaneseason2021 pic.twitter.com/LKliYX15co

— Cary Mock (@cary_mock) August 28, 2021

Ida narrowly missed New Orleans, instead inflicting catastrophic damage to parishes just west of the city before moving on and wreaking havoc in the northeastern United States.

We spoke with Mock after Hurricane Ida to grasp the differences between the two monster hurricanes and compare them with other cataclysmic storms in Louisiana history. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: You were tweeting about similarities between the 1812 hurricane and Ida days before Ida made landfall. Can you talk about the differences and similarities between the two storms?

A: They look pretty similar, in terms of the track. They both formed off of Jamaica and travelled through the Yucatan Channel.

Each storm has its own characteristics of course . . . some of them are more wind events—and Ida’s biggest impact was probably as a wind event—and some are bigger storm surge events because they’re bigger in size. Not necessarily Category 4, but systems so big, like Hurricane Katrina. There’s not as much wind when they make landfall, but they’re still big storm surge events.

I would say Ida was the strongest wind I can think of that Louisiana ever had in terms of a wind event, stronger than Katrina, which was more of a storm surge event. And I would say the 1812 storm fell right in between the two.

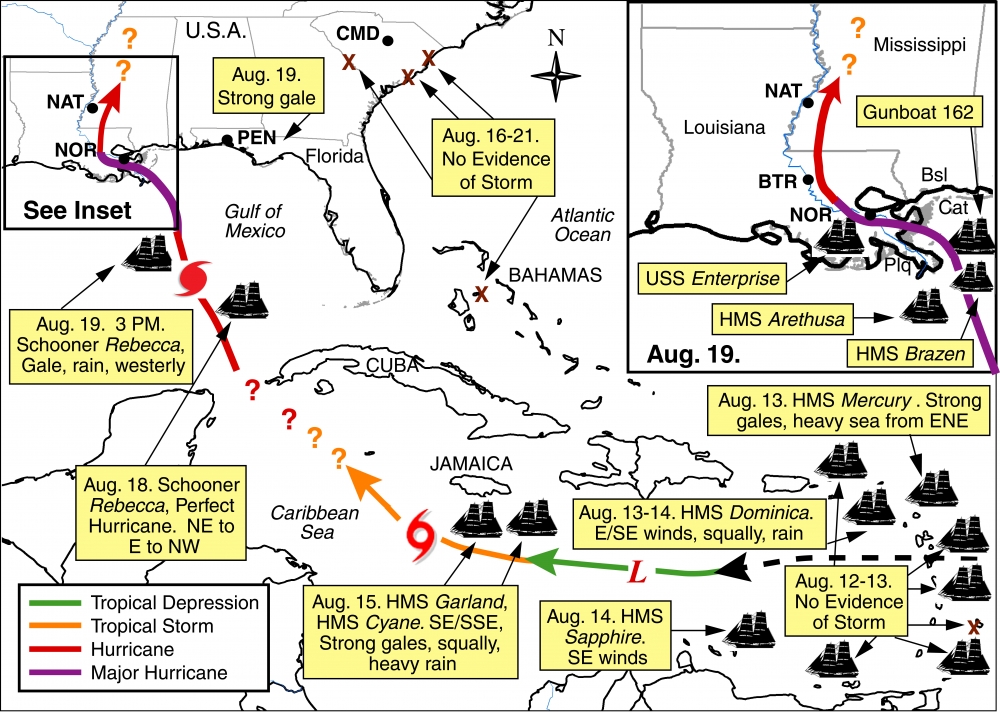

A map from the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society shows the track of the 1812 storm, according to Cary Mock and other climatologists who studied data on the August 1812 hurricane. (via Mock, C.J., M. Chenoweth, I. Altamirano , M.D. Rodgers, and R. García-Herrera. “The Great New Orleans Hurricane of 1812.” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 91: 1653–1663.)

How do you judge the intensity of a storm that happened over 200 years ago?

You look at the damage reports. In a storm surge event they’ll say that Lake Pontchartrain flooded over, so you can detect that. The 1812 hurricane certainly showed that, but with Ida—different levees, of course—but with Ida the levees generally held.

In a wind event, there aren’t as many killed, but there’s more structural damage, versus a storm surge where you just can’t get out.

I imagine that the effects would have been much worse without the sort of advance warning we get today.

The 1812 hurricane and Ida formed pretty quickly. New Orleans usually needs three days of advance warning for a evacuation, and they didn’t have three days [with Ida].

Governor John Bel Edwards, in the days leading up to Ida, referenced an 1856 hurricane as one of the strongest in Louisiana’s history. What can you tell us about that?

The 1856 storm is referred to as the Last Island Hurricane, which is officially listed as a Category 4, with winds at 150 miles per hour. I think it was a Category 4, but I don’t think it was quite that high. I looked at the barometer, and it wasn’t quite standardized. When you notch that storm down five or 10 miles per hour, I think Ida ranks a bit stronger.

It devastated the Last Island [located in the Gulf of Mexico, south of Terrebonne Parish], but there are records that show that once it hit mainland Louisiana, it decayed a bit. So, I’m sure you could say it was a real big hurricane, but around New Orleans, it probably wasn’t as bad as Ida.

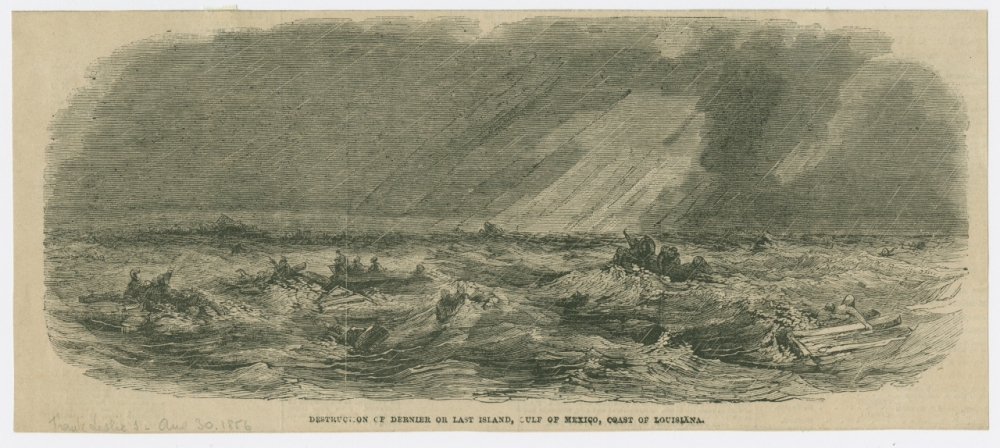

An 1856 engraving depicts the carnage of the suspected Category 4 hurricane that struck Last Island, Louisiana. At least 200 people of the 400 on the island died in the storm, according to the Washington Post. (THNOC, 1974.25.4.66)

You said that the 1812 hurricane was pretty much the worst-case scenario for New Orleans. You also said it would happen again.

Well the thing with Ida is, even a near miss of 20 to 30 miles makes the biggest difference in the world. New Orleans didn’t get Ida’s eyewall, but in 1812, the eyewall passed right over the city. So if [Ida] was just 20 or 30 miles to the east it would have been a lot worse. Probably power still out for months.

Storm surge would have been worse, too, because the eyewall would have been right near the Mississippi, right at New Orleans, so the levees could have failed.

So last year [2020], we got the eye of Zeta. That came right over the city.

Several eyes came over New Orleans, but they weren’t major hurricanes. There was the 1915 hurricane that was a Category 4 when it hit the islands offshore. But when it hit New Orleans, people say it was real bad, but I think it was probably a Cat 2 or Cat 1 at that point.

A 1915 photograph shows automobiles driving through New Orleans floodwaters after a powerful hurricane struck Louisiana. (THNOC, gift of Boyd Cruise in memory of Harold Schilke, 1981.309.7 vii)

Ida reversed the flow of the Mississippi River. What does it take for that to happen?

It has to be real big. I mentioned that when I wrote the paper about the 1812 hurricane. People either didn’t believe me or laughed at me. So I didn’t really think much about it since, until Ida.

It happened again, briefly, during Katrina, and it actually happened earlier in 1812 with the [New Madrid] earthquake—it happened twice that year. But in the 1812 hurricane, something like 40 ship protests [records of damage] showed that the ships went upriver, then back downriver, so I knew that had to be a big reversal of flow.

There have only been probably three or four times that the Mississippi River at New Orleans has reversed its flow. There was another instance that was pretty vague, I think it was Hurricane Gustav [in 2008]. But if it did happen, it only happened briefly.

You referenced a chart on Twitter, showing that, historically, hurricanes have come in spurts in Louisiana. Is there a phenomenon there, or is that just chance?

It’s a little bit of both. I would say for Louisiana, what really shows up is how many hurricanes you get there. Last year there were three hurricanes. That’s only happened three times that I know of: last year [2020], 2005 with Katrina, and 1860 it happened three times. But the fact that we’ve had two of those years relatively recently [is telling]. In a world of global warming, not only are hurricanes wetter and stronger, maybe for Louisiana there could be more frequent hurricanes per year. I would say that’s probably more concerning, something that catches the eye a bit more.

Louisiana Hurricanes, a long term perspective. Pre-1779 stuff is general, probably missing some storms. 1779-1871 stuff comes from a publication I did in 2008 with some minor updates. Busy times of hurricanes in Louisiana are not just a recent phenomena. #Ida #hurricane pic.twitter.com/0IVIaz8Ju0

— Cary Mock (@cary_mock) August 27, 2021

So the number of hurricanes is related to the conditions in the Gulf at that particular time?

Right. There’s this thing called the “loop current,” which is really warm ocean water—in Katrina it was really warm—and with Ida it happened to pass over that loop current. Any time we see that loop current, which is about 200 miles south of Louisiana, if something goes over it, that’s usually pretty bad.

That brings to mind this newer term “rapid intensification,” which seems to have emerged in the last few years. Has that phenomenon always existed, or is that something that we’re finding with the effects of global warming into a supercharged atmosphere?

Well, we’ve always had it, but we’re getting more of those cases now. At the same time, our technology is getting better, and we have more cases to study. We can fly planes and observe things a lot easier now, but physically and meteorologically, we think that global warming and the way the physics works in the atmosphere is more conducive to rapid intensification.

The other thing as to why it’s more common in the last five years is that we don’t know meteorologically what causes it. We think there’s little things in the eye, little swirls or things like that. We don’t know how that causes rapid intensification, but we think it has something to do with it. Like little eyes within an eye.

A 2005 photograph shows a flooded Canal Street in downtown New Orleans. Levee failures after Hurricane Katrina submerged much of New Orleans. (THNOC, gift of Chris E. Mickal, MSS 571.7.40.84)

So storms within an eye of the storm?

Yeah, the eye is not completely an eye, usually. It has little clouds, and little vortices inside it. I don’t personally know that much about it, but I do know that it’s considered sort of a mystery.

Ida went North and made more destruction in places like Philadelphia, New York, and New Jersey, and devastated some of those places. Going back to the 1812 storm, is there any evidence of damage further inland like we just saw?

Yes there is. Unfortunately, for 1812, there’s not that much data far inland, but there are hints that in Ohio, it was pretty much like New York for Ida. It was a big rainstorm and some heavy damage. I suspect that it went over Nashville, but the newspapers didn’t mention it.

But over Ohio, and maybe east of the Great Lakes like toward Toronto, there’s some evidence there that there was some pretty big storminess and that it may have been remnants of the 1812 hurricane.

You’ve alluded to this a few times, but because of climate change and global warming, should Louisiana expect more of these storms going forward?

Well I would say definitely prepare for that. You know it’s not just Louisiana but the whole Gulf Coast.

Do you think the levee system this time around spared New Orleans the kind of destruction that the city saw in 1812? Obviously it’s a different city, but back then you see the reports of the river and the lake converging.

I still think that if Ida was like 20 or 30 miles [to the east] that would have been very different. The New Orleans levees, from what I know, they’re designed to protect against an 11-foot storm surge in New Orleans, generally a high Category 3 hurricane. But if you get like a Category 5 like a Hurricane Camille that happened in Mississippi in 1969, I don’t think they would hold.

A direct hit is very rare, but it just takes one to do it. People like to take risks and whether it’s worth it or not—maybe I won’t be around the next 300 years when it happens, but what I meant by the worst-case scenario is it can happen.

Evacuees from the Lower Ninth Ward are shown crossing the Judge Seeber (N. Claiborne Ave.) Bridge by foot and boat after Hurricane Betsy in 1965. Even though it went west of New Orleans, Betsy caused major flooding in the city. (THNOC, 1974.25.11.76)

Just out of curiosity what was the last major storm that directly hit New Orleans?

I would say it was the 1812 [hurricane]. There might have been—I think the 1915 hurricane went over, but it wasn't a major hurricane at that point.

In 1812 the sustained winds at that point would have still made it a major hurricane when it passed over?

Yeah definitely; [the 1812 storm] would have the sustained winds at that point to make it a major hurricane when it passed over. Betsy [in 1965] would have been downgraded by [the time it approached New Orleans]. It was a little bit to the west, Betsy, and it had a similar track [to the 1812 storm]. Yeah, Betsy was another one [where] 20 or 30 miles would have made the biggest difference.