“Undoubtedly our artistic climate is going to change through the world situation. . . . I think there is going to be a vast hunger for life after all this death—and for light after all this eclipse. . . . People will want to read, see, feel the living truth and they will revolt against the sing-song Mother Goose book of lies that are being fed to them.”

—Tennessee Williams, November 29, 1941

A Streetcar Named Desire premiered on Broadway on December 3, 1947, receiving a seven-minute standing ovation. The production went on for a remarkable 855 performances.

The play struck a deep chord in the post–World War II United States, where people struggled to find their places in a rapidly changing social order. Audiences had lived through one of the most violent periods in human history, and to many, the name of the play’s lost ancestral home, Belle Reve—“beautiful dream”—evoked fading prewar notions of morality and societal convention. Viewers were ready to embrace, as Williams had predicted in 1941, “the living truth” of their new era.

In celebration of the 75th anniversary of this seminal drama, The Historic New Orleans Collection presents Backstage at “A Streetcar Named Desire,” which combines selections from THNOC’s wide-ranging Tennessee Williams holdings—many of them seldom displayed—with loans from the Harry Ransom Center, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the New York Public Library, and Wesleyan University.

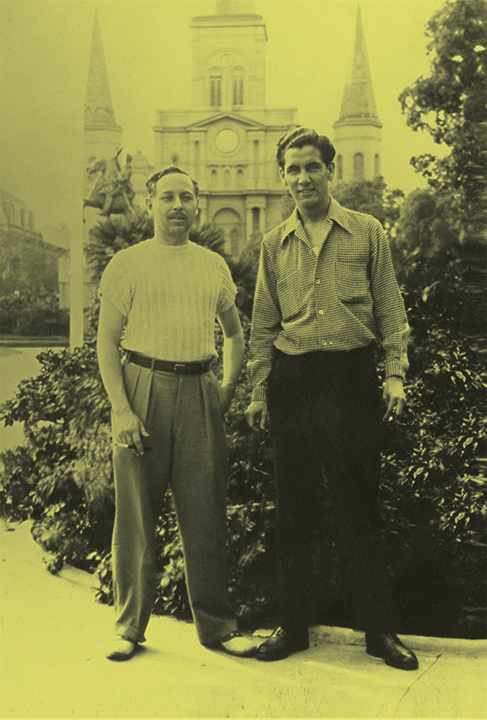

Tennessee Williams (left) and his partner, Pancho Rodriguez y Gonzalez, in Jackson Square in 1945. (Todd Collection at THNOC, 2003.0228.1.1)

“This woman had better be good,” noted an annoyed Williams in a telegram to his literary agent, Audrey Wood, in April 1947. He was referring to Irene Mayer Selznick, whom Wood had chosen to produce the play. Selznick was well connected—she was the daughter of movie mogul Louis B. Mayer and the soon-to-be ex-wife of producer David O. Selznick.

Selznick proved herself not only by investing her own money, but also by persuading Elia Kazan, the most sought-after Broadway director at the time, to take on the project. Selznick and Kazan put together a legendary cast that made Streetcar an iconic contribution to the history of US theater.

Irene Mayer Selznick produced A Streetcar Named Desire and, through her Hollywood connections, helped pave the way for the play’s film adaptation. (Courtesy of Tennessee Williams Collection, Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin; Louise Dahl-Wolfe Archive © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents)

The director’s notebook features extensive, detailed descriptions of the characters as Kazan conceived them—Blanche, for example, is described as “an emblem of a dying civilization, making its last curlicued and romantic exit”—along with notes Williams gave him during rehearsals. Williams himself features as a character in the notebook as well. “Blanche,” Kazan writes, is Williams: “out of place, unappreciated, a stranger in the modern, rough, coarse South.”

Tennessee Williams used this typewriter while writing Streetcar. (THNOC, 2018.0393)

Wanting Williams’s blessing to cast Marlon Brando as Stanley, Kazan gave Brando, 23 at the time, $20 to travel to Provincetown, Massachusetts, to do a reading for the playwright. Instead of using the money to pay for travel, Brando and his girlfriend hitchhiked. The actor arrived a few days late, promptly fixed a plumbing emergency for Williams, and then astonished the playwright with his reading. Williams wrote to Wood, “A new value came out of Brando’s reading which was by far the best reading I have ever heard. He seemed to have already created a dimensional character, of the sort that the war has produced among young veterans.”

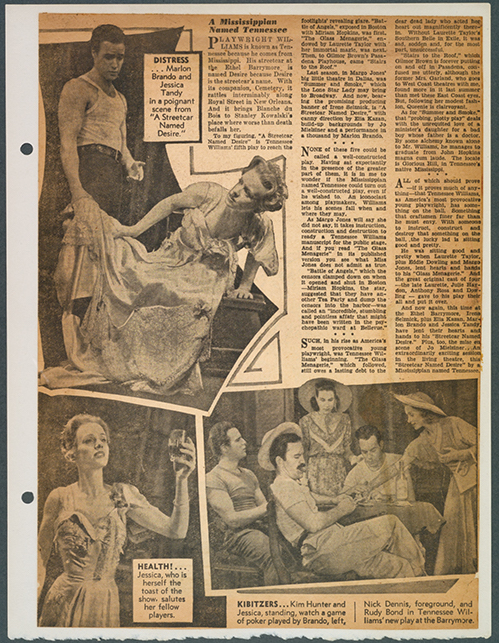

A page from a scrapbook compiled by Irving Schneider containing clippings relating to the original production of Streetcar. (Gift of Faulkner House Books, 2004.0141)

Brando’s Stanley can be heard menacing Jessica Tandy’s Blanche in a rare recording on exhibit: excerpts of the play produced for radio broadcast. No film exists of Tandy’s acclaimed performance, but the recording offers an auditory glimpse of Blanche as Tandy introduced her to the world.

Selznick’s Hollywood connections and the popularity of the stage production ensured that the film version of the play quickly took shape, with almost all the original Broadway team. Vivien Leigh replaced Tandy as Blanche at the insistence of Warner Brothers: Leigh had greater box office appeal, having starred in Gone with the Wind and in the British stage version of Streetcar. Testifying to her success is Leigh’s 1952 Best Actress Oscar statue, which travels across the Atlantic for this exhibition.

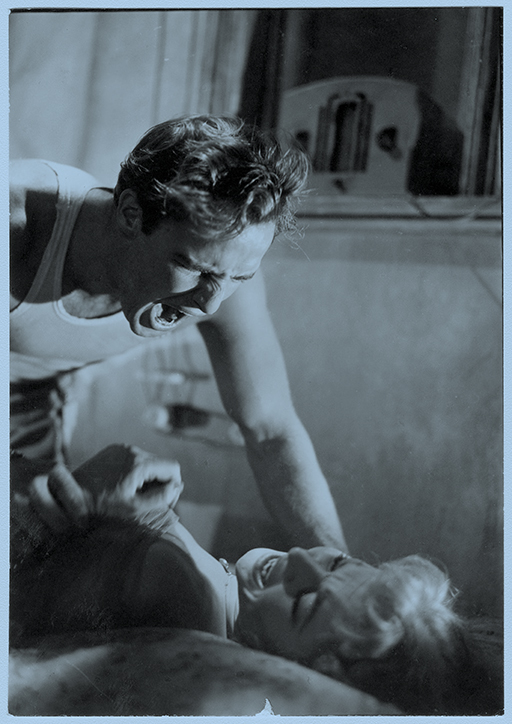

Stanley (Marlon Brando) assaults Blanche (Vivien Leigh) in the film adaptation of Streetcar. (Todd Collection at THNOC, 2001-10-L.1777)

Perhaps the biggest challenge in adapting the play for the screen was the script. Guidelines established by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) restricted film content. The MPAA’s censors required numerous changes to the script, which included drastically rewriting the ending to show Stanley being punished for his rape and subsequent institutionalization of Blanche. Despite these major revisions, Kazan’s film proved as popular as the Broadway production.

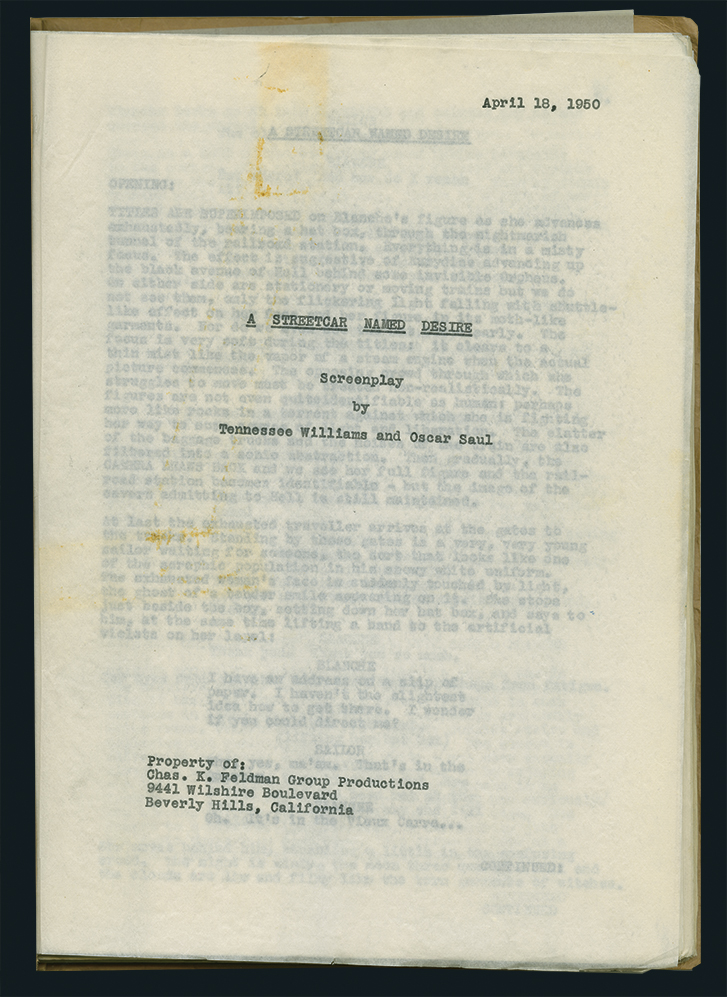

Tennessee Williams’s copy of the screenplay for Streetcar. (Todd Collection at THNOC, 2013.0128.2)

Streetcar’s reflection of a crumbling social order appealed as much to Latin America, postwar Europe, and beyond as it did to US audiences. Productions in Brazil, Cuba, and Mexico were immediately staged in 1948, and within 10 years, important productions had appeared in Greece, Italy, London, Paris, Sweden, Japan, and Korea, and Farsi and Arabic translations were published. The first major Soviet production premiered in 1970, and 1988 saw the first performance of the play in mainland China.

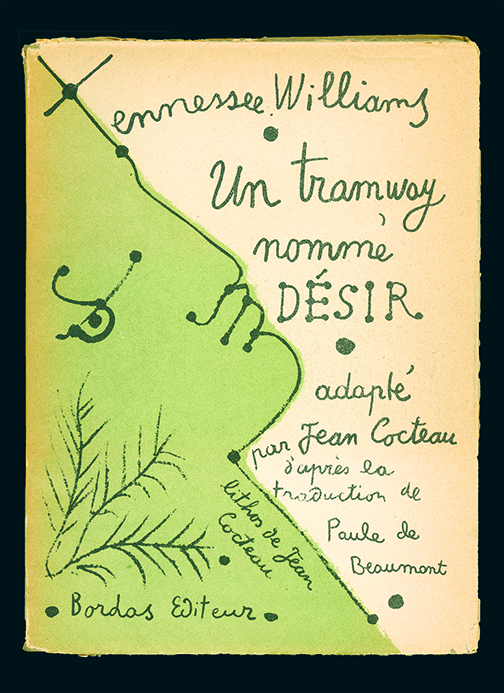

Director Jean Cocteau adapted Streetcar for French audiences under the title Un tramway nommé Désir. (Todd Collection at THNOC, 2001-10-L.3715)

A Streetcar Named Desire has become an icon of the US stage and continues to be translated and performed throughout the world. The play has become a renewable resource in popular culture, inspiring parodies (the exhibition features a clip from an episode of The Simpsons entitled “A Streetcar Named Marge”) and experimental productions. Its deep connection to fundamental human struggles has been used to explore issues of class, gender, and race in a wide variety of mediums, including a ballet and an opera.

Stella (Kim Hunter) embraces Stanley (Marlon Brando) in the film adaptation of Streetcar. (Todd Collection at THNOC, 2001-10-L.1246)

Every generation of literature and performance scholars finds new facets and materials in the play. Streetcar can be read as Williams’s coded exploration of US discomfort with Blackness, World War II veterans, transgressive sexualities (men’s and women’s), and more. Replace “US” with “societal” and the play wrestles with tensions in whatever historical and geographical context a director chooses. The 2022 issue of the Tennessee Williams Annual Review features explorations and photographs of Streetcar’s first productions in Brazil and the Soviet Union, introduced in both countries by some of the 20th century’s most important theater directors. The issue also includes a special image section devoted to THNOC’s exhibition, giving far-flung Williams fans a selection of the rare behind-the-scenes photographs and other archival materials on view.

This article appears in the Spring 2022 issue of THNOC Quarterly, which can be viewed here.