Interpretation Assistant Malinda Blevins details the process of turning THNOC's founder's diary into content for guided tours. A version of this article appeared in the "On the Job" feature of the Winter 2019 edition of The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly.

History, for me, is best conveyed not in lists of facts but in stories of people’s lives.

As a member of THNOC’s visitor services staff, I often surprise guests when I tell them we don’t follow a script when leading tours. What could be new to say about, for example, the Williams Residence—the 1889 townhouse where THNOC’s founders, Leila and L. Kemper Williams, lived for 17 years? A lot, as it turns out.

Kemper Williams's study has been preserved in The Historic New Orleans Collection's Williams Residence.

We are always on the hunt for new things to say about the Williamses and the Williams Residence, often conducting our own research. The goal is to be able to adapt a tour, on the spot, to each unique set of visitors and their interests and questions, helping new guests feel engaged with our organization and giving repeat visitors a slightly different tour each time.

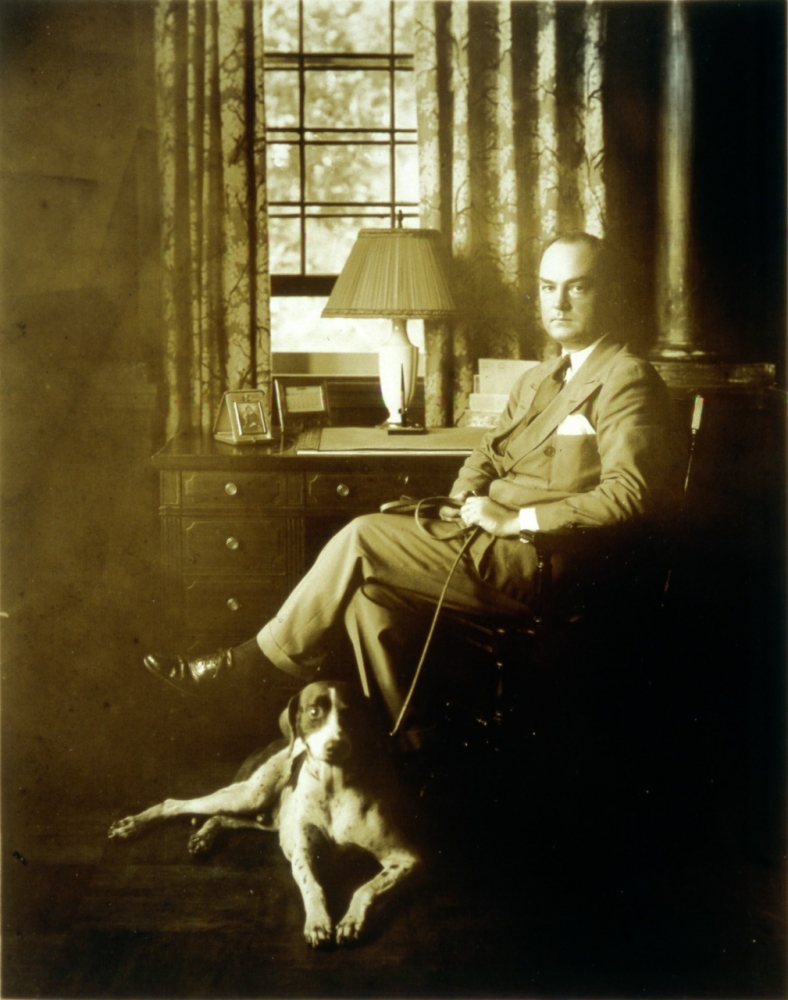

Several years ago, I began exploring a tour-enhancing trove: Lewis Kemper Williams (left), a philanthropist, businessman, and US Army veteran who attained the rank of brigadier general, kept approximately one diary per year from 1948 to 1971. I began reading the diaries in 2014, in preparation for THNOC’s holiday tours, browsing them to learn about the Williamses’ Christmas and Carnival traditions. Each time I opened one, I found myself captivated by the minutiae and overall picture of the general’s life and personality. I was surprised, for example, to see that Kemper tended to root for the underdog—in political races as well as the Sugar Bowl, which he attended without fail. His handwriting enhances the information carried in his words: when he expresses aggravation (usually in regard to a business deal), he presses down hard on the paper, so now when I see that pressure applied elsewhere, I can guess that he is frustrated. I was hooked, and decided to read the diaries in order, in their entirety.

The diaries confirm the general’s reputation as stern and disciplined, but they also reveal him to be funny and frequently self-aware, much more interested in his sugarcane operation than in the oil business that was the family’s primary asset at that point. I’ve learned from him that the cane has to be processed immediately upon being cut, that the processing plants run 24-7 during the harvest season, and that the cane fields have to be burned every three years. A November 1948 entry summarizes his frustration with the wet weather: “It is most exasperating. Too much rain interferes greatly with the harvesting of the crop, and the warm weather promotes further growth and prevents normal buildup of sugar in the cane. . . . We are used to bad weather during grinding, even with colder weather, but it is annoying just the same.”

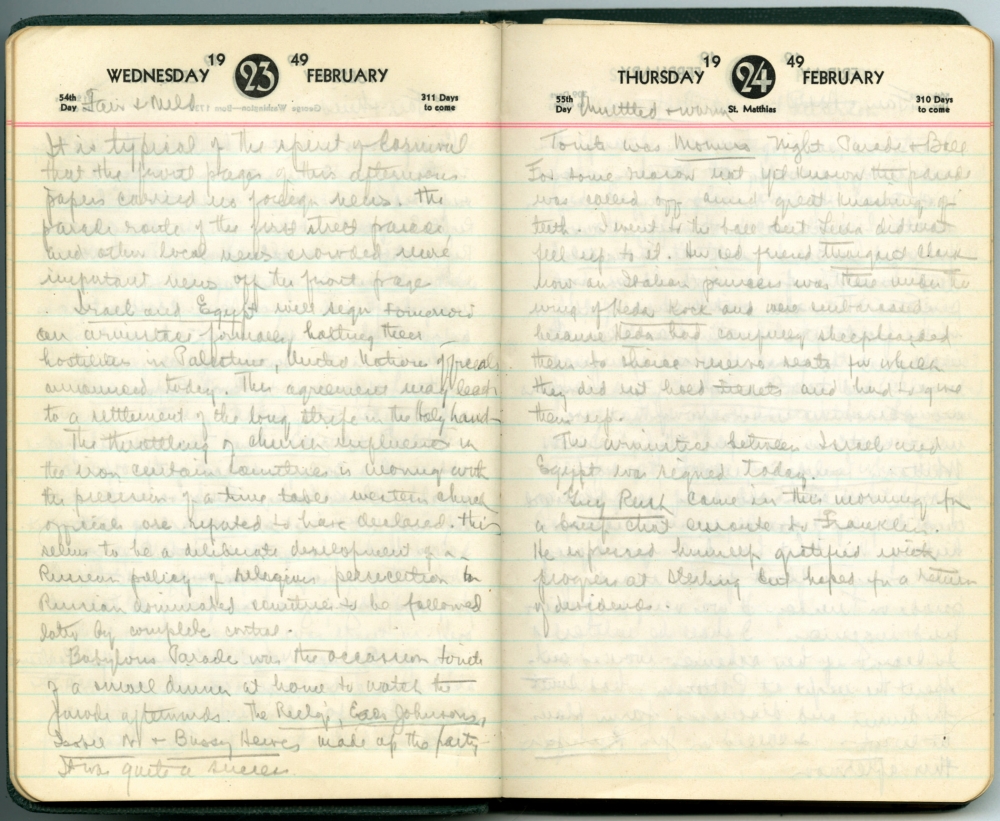

A page from Williams's diary from 1949. Blevins can sometimes tell Kemper's mood by fluctuations in his handwriting. (THNOC, 97-63-L.5 pp 23–24)

Such exacting, business-minded entries are juxtaposed with glimpses of Kemper the dog lover. He dotes on the couple’s dachshunds, calling from overseas while on vacation to ensure that they are well and spending more than one holiday at the vet with a dog who needs surgery or has swallowed a Christmas ornament. I could probably give an entire tour focused on the Williamses’ dogs!

Kemper is shown with the couple's two dachshunds, named Sherry and Crackers. (THNOC, 79-78-L.6 p.21)

A devoted husband, Kemper writes about Leila almost every day—her health (fragile); her labors for her father, siblings, and nieces and nephews (tireless); her cooking (generally “appetizing” or “very satisfying”). Gifts and favors abound: “I picked up 11 dwarf Meyer lemons [trees] for Leila.”

Kemper finds the “ubiquitous cocktail parties” on a European cruise to be tedious, but he tolerates them because Leila is “vexed” to miss her daily cocktail. When, while on holiday in Sri Lanka in 1955, Leila awakens with a bad headache, he goes jewelry shopping, purchasing a sapphire clip to cheer her up.

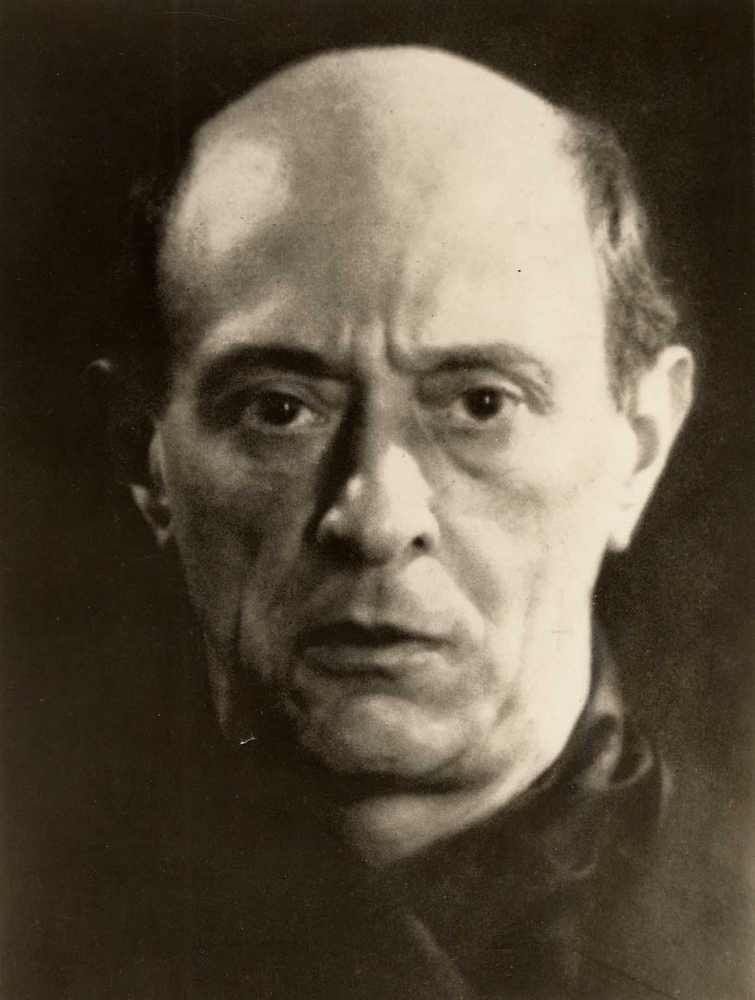

Leila’s personality emerges: Kemper installs a television antenna in 1956, but Leila is so disturbed by the TV that she moves it to the servants’ break room. He admires her determination to attend every meeting of the Kemper and Leila Williams Fund, the educational foundation through which they donated money to schools and other causes. An entry describing a 1948 party is interesting in its mention of the composer Arnold Schoenberg (left) but also moving in its sincere appreciation of Leila’s ability to host: he describes the event as “almost a fairyland with the candles enclosed in paper bags and Japanese lanterns hung in the trees. . . . Even little old Dr. Schoenberg, one of the greatest living composers, seemed to enjoy himself.”

Kemper’s tight handwriting on the day of Leila’s funeral—December 15, 1966—conveys both deep emotion and resilience: “Never by lecture or dogma but by example alone she creates in me a desire to be worthy of her. . . . It will be a lonely existence for me, but I think I can cope with it.” Reminders of her help him to grieve: he later finds humor in the fact that Leila’s love of furs led her to secret them about the house, where they continually surprise him, practically popping out of cupboards and drawers.

Leila Williams is shown outside of the couple's French Quarter home. (THNOC, 79-78-L.9)

Kemper is not without biases and rigidities. The opinions expressed in his diaries are a window into the worldview of men of his era and class. For example, he does not question the doctors who determine that Leila—who suffered from frequent headaches and the occasional “ordeal,” the details of which are kept vague—needs “to forget about herself.” He views a job applicant with suspicion for driving what strikes him as too nice a car for a butler (a Cadillac). The couple’s longtime cook shows up to work inebriated, and Kemper describes it as a “domestic tragedy”; he carefully combs his stock of spirits to ensure the servants haven’t been depleting them. In an entry from November 1948, he labels Eleanor Roosevelt a “disturbing element” in politics for alienating the local Dixiecrats with her “negrophile pronouncements and actions” in support of civil rights for African Americans.

Kemper is shown with an unidentified employee. Williams's diaries reveal his biases regarding women and people of color. (THNOC, 2017.0497.22)

Part of an interpretation assistant’s job is to provide historical context: when I talk with visitors about THNOC’s founders, I try to appreciate, respect, and humanize them without idealizing them. More broadly, the fuller portrait of Kemper and the histories of all the individuals involved with the Williams Residence have much to teach us about Louisiana history. To me, the best tour is one in which visitors ask more questions than I can answer, because the visit becomes a conversation, not simply a recitation, and I am left with new avenues for research. The more I read Kemper’s diaries, the more tools I have to surprise and intrigue my audience, making me better able to illuminate the man behind the legacy.

Tours of the Williams Residence are available Tuesday–Saturday at 10 a.m., 11 a.m., 2 p.m., and 3 p.m. and on Sunday at 11 a.m., 2 p.m., and 3 p.m. Tours are $5 and free for members.