Material culture historians use objects from the past to help understand the people, culture, and society in which those objects were made and used. Every year THNOC’s Decorative Arts of the Gulf South (DAGS) research project sends fellows on a scavenger hunt through Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana to find and document the pieces that tell the story of the region’s pre–Civil War history. But material culture doesn’t live only in the past; it lives in the present, too. We all have objects that are key to understanding our own personal stories and to understanding our world.

This got some of THNOC’s Visitor Services staff wondering if we could apply what material culture historians use to understand stories from the past on stories in the present. So this summer, we asked our audience the question: if a historian were to study you 150 years from now, which possessions would be key to understanding your life?

The responses we got ran the gamut from treasured family heirlooms to relationship mementos, religious artwork, and even a taxidermy snake head! What all of these varied objects have in common is that they hold a deep personal significance to someone, and, when we look at them all together, they can shed light on the experiences of people here in the 21st century. Here’s a sample of 10 stories we received; some entries have been edited for length, style, and typos.

1. A bowl deep with family history

My grandmother, Lettie Boseman—known as Momma to me and my cousins—loved to bake tea cakes, a cookie that is tradition to many African American families. She baked them for her nine children and would continue to bake them for the large tribe of grandkids that would follow.

My thoughts are that she learned this gift of baking from the workers at Nottoway Plantation in White Castle, Louisiana. She and her mom, Louvenia (my great-grandmother), lived there for a period of time. I was exceptionally close to Momma and loved to listen to her stories and watch her cook. Luckily for me, my family lived just around the corner from her. When she got the urge to bake and the tea cakes came out of the oven, that sweet phone call would come across the line. “Les, I baked tea cakes.” Off I went to retrieve my stash.

They would usually be awaiting me in the large yellowware bowl on the Formica kitchen table. I would grab a brown paper bag and stuff as many as I could in it for me and my three siblings. No two batches were ever the same. There was no need for fancy cookie cutters in her kitchen. She usually grabbed whatever glass was nearby to cut out the dough. If there was a bottle top available, you might find that shape pressed onto a tea cake as decoration. The warmness would leave spots of butter stains on the bag. I could never resist eating a few on my slow walk home. I admit to my selfish consumption and clearly not dividing the batch evenly. But how would they know?

After Momma’s passing in April of 1998, I felt a need to honor her memory and those wonderful batches of tea cakes. Of course, upon her answering God’s call, the one item of hers that I had to have was that old, worn yellowware tea cake bowl. Following tradition, I’ve been known to whip up batches of tea cakes on a whim to share with my family and friends on special occasions. To represent the love I will always hold in my heart for my grandmother, the odd shapes have been replaced with a different shape—a heart.

—Leslie Smith Everage, Louisiana

2. The Jenny Lind bust that was worth more than money

When Jenny Lind, the Swedish opera singer brought to America by P. T. Barnum, came to New Orleans, my great-great-grandfather was there to hear her. As with modern concerts, they were selling memorabilia—or “merch,” as the kids today refer to it. My great-great-grandfather was smitten with the Swedish beauty and purchased a plaster bust, a lithograph, and a jewelry box of her likeness. These items were passed down in our family along with the belief that the bust was very valuable. At times of financial lows, the family was always comforted by this belief. It was said to all the generations, if things get really bad, you can sell the Jenny Lind bust to help you get through the rough times.

In the early 1990s, my great-aunt was the keeper of the Jenny Lind items. She was in the early stages of Alzheimer’s and had come to live with our family in Alabama and, of course, she brought Jenny with her. Sotheby’s of London was presenting an antique appraisal at the local library, so with great care, wrapped in multiple layers of protection and held in my mother’s lap, we took Jenny to be appraised. The verdict was that the items would have sold for about one dollar at the time. The 1990 value was around $100. So much for Jenny helping the family in times of financial woe.

We never told my great-aunts about the appraisal. The true value of Jenny was the financial comfort she brought to a family during the Depression and other times of economic downturn. The story of Jenny is much more valuable than Jenny herself.

—Laura Lee Jaworski, Virginia

3. A grandfather’s banjo

My grandfather Charles Bocage was born January 14, 1900, in New Orleans. He played banjo by ear. He was also an occasional vocalist. He joined the Armand J. Piron band as a banjo player. He played with his brothers Henry on bass and Peter on trumpet, as well as my great-uncle Lorenzo Tio Jr. on clarinet. In 1928, Charles joined his brother Peter in the Creole Serenaders, along with my great-uncles Henry, Lorenzo, and other noted musicians. I recently learned that my grandfather Charles quit playing the music at night that he loved to only work as a train porter because he had a heart attack in 1950. He died in New Orleans in 1963.

The Bocages were highly regarded by their peers. Professor Alden Ashforth told me, “They were widely admired for their high standards of musicianship and upholding those standards.”

While in New Orleans many years ago, I was able to visit the Hogan Jazz Archives at Tulane University. I purchased an audio copy of an interview my grandfather Charles did with jazz historian Richard Allen. Upon returning to my Aunt Carol’s house, we played the recording. I looked over to see tears running down my aunt’s face. She said, “It’s been a long time since I’ve heard my Daddy’s voice.”

Their celebrity made it possible for me, future generations of my family, and others to know how my grandfather spoke and the contributions he, his brother, and in-laws made to early New Orleans music. They may not have been a big commercial success, but they were very rich because of the admiration from their peers. That is something we can all be proud of. I certainly am glad to be from a family with such a proud musical and ethical tradition.

—Charlotte Bocage, California

4. Three Thangkas with life lessons

In 2012 I made an extended solo trip to India. I spent several months in Himachal Pradesh, just a short walk to the temple complex and [exiled] home of the Dalai Lama. At one point I went on a silent retreat and the main temple room was adorned with thangkas—ornate Tibetan silk paintings used as teaching tools. Once the retreat ended, several of us—all complete strangers—celebrated together in what became an unforgettable evening. The next day I woke up and walked to a shop on recommendation in search of a thangka. I ended up adopting three.

These paintings are sewn onto multi-layered brocade frame, supported by wood scrolls, and protected by a silk cover. They’re designed as religious objects for nomadic people—easily rolled and transported, wrought with Buddhist symbolism. Most depict historical events or myths.

There were many to sort through and [the seller] explained the meaning of each over several cups of chai. I was guided to a fabric vendor to choose colors and brocades for each frame, and then to another shop, all materials in hand—a seamstress. I came back the next day to pick up the finished thangkas and carried them around India encased in a PVC tube with duct tape shoulder strap until I came back home to New Orleans. Nearly a decade later, they hang in my dining room. These thangkas are the first thing I put in the car during hurricane evacuations.

—Dhani Adomaitis, Louisiana

5. A paperweight heavy with significance

Years ago, I was a glassworker. I made perfume bottles, vases, ornaments, oil candles, pendants, and other objects in a production studio in New Orleans. A nice young fellow I’d just met at the synagogue two blocks from where I lived at the time came in to purchase a few paperweights: one for himself, one to send to his parents as a gift. This paperweight is one I made in 1997.

Five years after the purchase of this hefty globe, I married the nice young fellow in that synagogue.

—Leigh Checkman, Texas

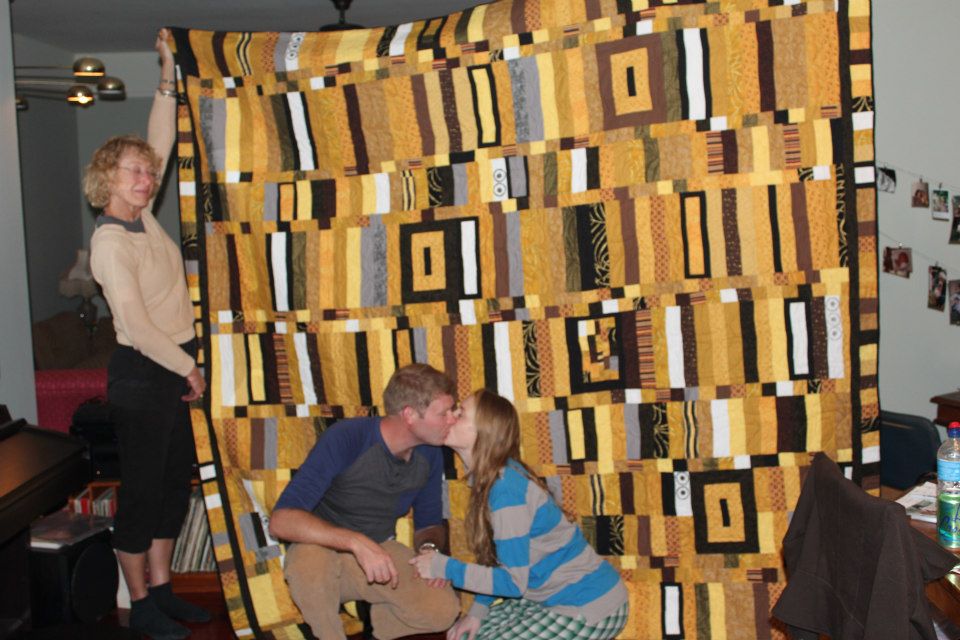

6. A quilt sewn with family history

Two days before my husband and I got married in 2012, my mother-in-law, Suz Cleaver, presented us with this gorgeous quilt made by more than 20 family members and friends based in northwest West Virginia and Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the two areas where my husband grew up. Suz coordinated the entire project: inspired by Gustav Klimpt’s The Kiss, she selected fabrics in rich gold, yellow, black, white, grey, and brown. She provided the fabrics to far-flung participants and hosted sewing meetups with local friends in West Virginia. Each person made a quilt square, and Suz assembled them all together into the final product.

Receiving that quilt on the eve of the wedding festivities set the stage for the big event: “This is really happening!” It made me feel tied to history, to the old ways of community-based support for newlyweds. Being able to hold a material representation of those friends’ support meant—still means—the world to both of us. Moreover, the quilt is stunningly beautiful! It’s a style and color palette I would never think to select for myself, which makes its beauty even more of a gift.

—Molly Reid Cleaver, Louisiana

7. A fearsome snake held dear

I can’t recall where he got it, but I inherited a taxidermy rattlesnake head from my dad after he passed away. My dad had an affinity for snakes, which he passed on to me. I was a daddy’s girl growing up, and I’m sure part of the reason I developed a liking for snakes was to please my dad. The object itself is grotesque. I don’t know much about taxidermy, but it doesn’t seem particularly well preserved, which adds to the gross-out factor. Still, it’s one of the objects that I cherish the most.

—Christy Lorio, Louisiana

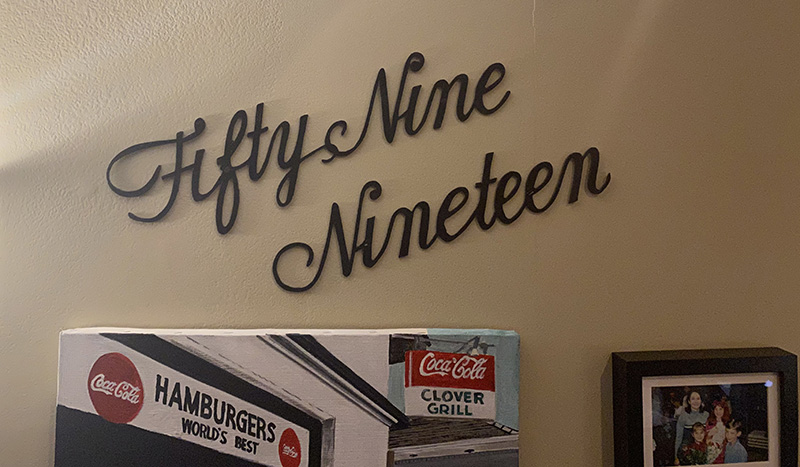

8. Numbers to remember Katrina’s wrath

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, we were living in a slab-on-grade brick house in Gentilly. That house at 5919 Chamberlain Drive, along with every other house for miles around, was flooded when the London Canal breached a few streets over. We had evacuated and were safe, but the house and everything in it were heavily damaged by flood water from Lake Pontchartrain.

Right away, I knew we would not be returning to that house, fearing it could easily flood again. Instead we planned to demolish the old house and build a new, elevated home at the same location. Just prior to demolition, I removed the metal script address from the brick facade and saved it for later use. We had plans drawn up and talked to several home builders but in the end could not find anyone who could build our new home at an affordable price.

We ended up selling the land as part of our Road Home settlement and bought an unflooded house in Faubourg St. John where we still reside today. We still had the address, so I hung it on the wall in the living room of our new home. It reminds us of the good times we enjoyed in our old neighborhood at that ill-fated house.

—Timothy Ruppert, Louisiana

9. A fan passed down for generations

In 1895, Barbara Weber married Herman Winter in St. Mary’s Assumption Church. Barbara’s wedding portrait shows her holding a fan, which appears in the shadowbox picture frame. Barbara’s daughter, my great-aunt, Anna M. Winter (born in 1903) passed these treasures on to me, along with wonderful stories of growing up in New Orleans in the early 20th century and the Roaring Twenties.

—Jan Davis, Louisiana

10. A boat borne by adventure

This was my beloved 1997, 21-foot Reno Lake Skiff. Its inside layout was my design and was laid up by the Reno Boat Works in Manchac, LA. It was powered by a brand-new Honda 90hp motor that was revolutionary at the time for its quiet and fuel efficiency. It was a pretty snazzy rig in my mind.

These skiffs are indigenous boats, made for the bayous, rivers and open waters in and around the Lake Pontchartrain Basin. They are known for their affordability, ruggedness, utility, lake-worthiness, low freeboard, shallow draft, handling—and good looks. They are made by just a handful of local boat yards and are used by both commercial and recreational boaters.

The “Black Boat” was perfect for me, and we went on many great adventures together, exploring many, many places across Louisiana’s coastal wetlands, from the Atchafalaya to Breton Sound, and we had gloriously wild times out of our home port on the Tickfaw River and Lake Maurepas.

—Ben Taylor, Louisiana

For more stories from this series, follow @PiecesOfYourStory on Instagram. To share an object (and story) from your collection, visit THNOC’s PiecesOfYourStory webpage.

The Pieces of YOURstory project is based on THNOC’s 2021 exhibition Pieces of History. For more on material culture in the Gulf South, visit the exhibition webpage.