When Carnival time comes around, THNOC’s Visitor Services staff stay ready to field questions about New Orleans Mardi Gras history, traditions, and lore. The customs of the city’s famously enigmatic parading krewes attract special attention. For all the details, a free guided tour of the exhibition Making Mardi Gras is a great starting point—but in the meantime, four of THNOC’s interpretation assistants have assembled this FAQ to whet your krewe curiosity.

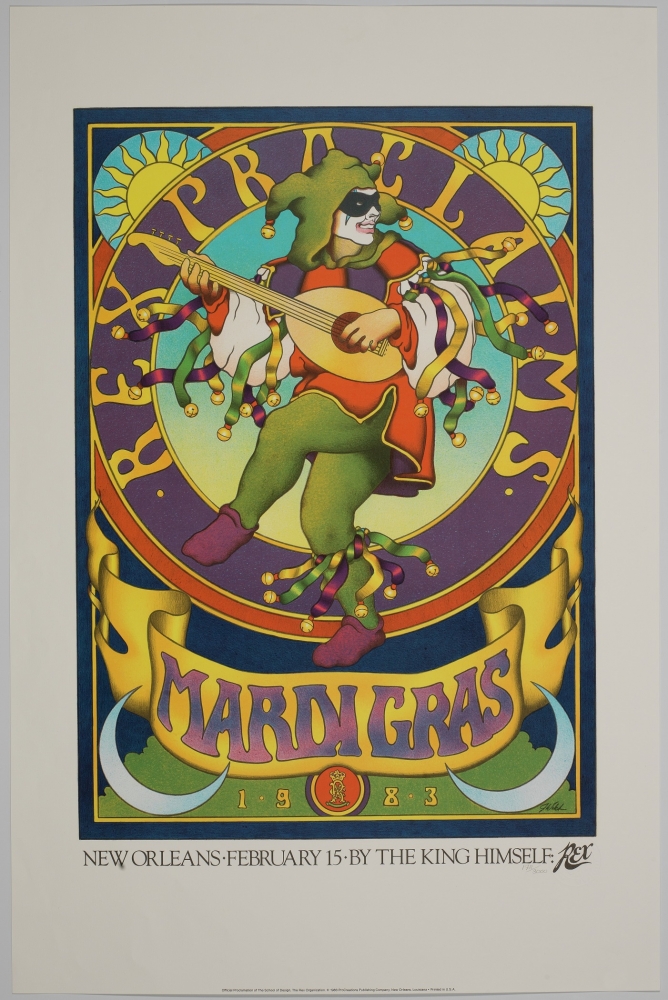

Jean Welch designed this Rex poster for Carnival 1983. Rex traditionally declares the start of Mardi Gras by official proclamation. (THNOC, 1983.30)

What’s a krewe, and who’s in charge of it?

Carnival clubs, with their kings and queens, royal courts, and bals masqués, give New Orleans Mardi Gras a distinctive flavor. At the center of local parading customs is the peculiar term “krewe” itself. A krewe is, simply, a club or organization that exists to celebrate Carnival.

But while a krewe has royalty, the positions of king and queen are merely ceremonial. The identities of the queen and her maids are usually public, while the identities of kings are often secret—Rex being a notable exception. The power behind the throne, however, is the captain, whose identity is typically kept secret. When he appears in public, he is always masked and often riding a horse in the parade flanked by his lieutenants.

The captain of the Mistick Krewe of Comus (center left) the presents Queen Jessie Wing Sennott to the king, standing at rear with his pages, at the krewe’s ball in 1962. Comus traditionally keeps the identities of the king and captain a secret. (THNOC, 1987.2.7)

The captain is, in many ways, the CEO of the krewe. His position is usually an elected one, and the office is responsible for running the day-to-day and seasonal operations and activities of the krewe. These activities include the annual ball and parade, as well as other events of varying size throughout the year, often including charitable endeavors. The captain delegates some of his responsibilities to various officers in the krewe.

So, the next time you hail Rex or see the Zulu king (be it on Rampart and Dumaine or on the modern St. Charles Avenue route), keep an eye out for the captain or president, the real power behind the throne. —George Schindler

This 1965 costume design for the Krewe of Sparta’s captain, by designer Larry Youngblood, features a yellow plumed headdress with matching yellow tunic and cape. (THNOC, gift of Elizabeth Y. Canik, 2017.0436.102)

How did “If Ever I Cease to Love” become the official song of Rex?

In the fall of 1871, 21-year-old Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich Romanov led a delegation of the Russian navy on a goodwill tour of the United States, which culminated in New Orleans at the height of the 1872 Carnival season.

The grand duke’s visit to New Orleans is interwoven with much Mardi Gras lore, including the idea that the first Rex parade was organized in his honor.

The primary goal of the Rex parade, organized by local businessmen, was to boost the city’s economy and national reputation while formalizing Carnival festivities to center status and pageantry over more decentralized, working-class, and racially diverse processions.

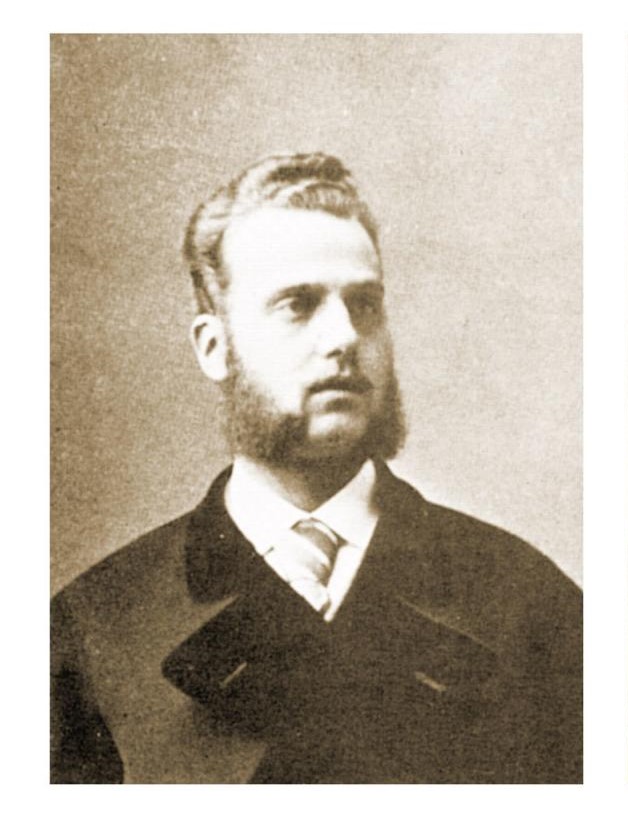

Alexei Romanov, grand duke of Russia, concluded his goodwill tour of the United States in New Orleans just in time for Mardi Gras 1872. The rumor mill linked him romantically to English singer Lydia Thompson, whose tune “If Ever I Cease to Love” was the song of the season. The brush with royalty and the overall popularity of the song inspired Rex to adopt it as its official anthem, and it remains so today. (Photograph courtesy of Arthur Hardy)

If the 1872 parade was not organized for the sole purpose of celebrating the grand duke, his visit did inform the occasion and contributed to the general excitement of Mardi Gras. Local newspapers published a satirical letter presented by Rex, “King of Carnival,” to his royal colleague Alexei: “His Royalovitch Highnessoff the King of Carnival officially welcomes to New Orleans his royal cousin,” the letter began.

Alexei enjoyed the parade from a viewing platform in front of Gallier Hall. As the various bands marching in the parade arrived, each allegedly paused to perform the Russian imperial anthem. Also played many times that night, as well as at virtually every ball and event the grand duke attended while in New Orleans, was “If I Ever Cease to Love,” a tune popularized by the actress and burlesque performer Lydia Thompson. Rumors—unsubstantiated—abounded that the young Romanov had become infatuated with Thompson after seeing her show, Bluebeard, during his US tour, and so the song followed him to New Orleans. By the end of his visit, “If Ever I Cease to Love” had become not only the song of the season but the official song of the Rex Organization—and it remains so today. —Dylan Jordan

This Southland Records release from Carnival 1954 was the first record to render “If Ever I Cease to Love” in the style of traditional New Orleans jazz. The ensemble, led by trombonist Johnny Wiggs, featured Paul Barbarin on drums. In a January 1954 letter to his nephew Danny Barker, he wrote that he gave the tune “that Parade Beat,” helping to update the 1871 original for modern listeners. (THNOC, gift of the Rex Organization, 2006.0032.52)

When did all-women krewes begin?

Like Rex, the other early Carnival krewes were exclusive, permitting only well-to-do white businessmen as members. Membership in a social club that paraded in the streets was considered highly improper for women. However, New Orleans women were not inclined to forever peer from behind window curtains during Carnival festivities, nor were they content to be put on display as queens and maids or serve only as dance partners at krewes’ balls.

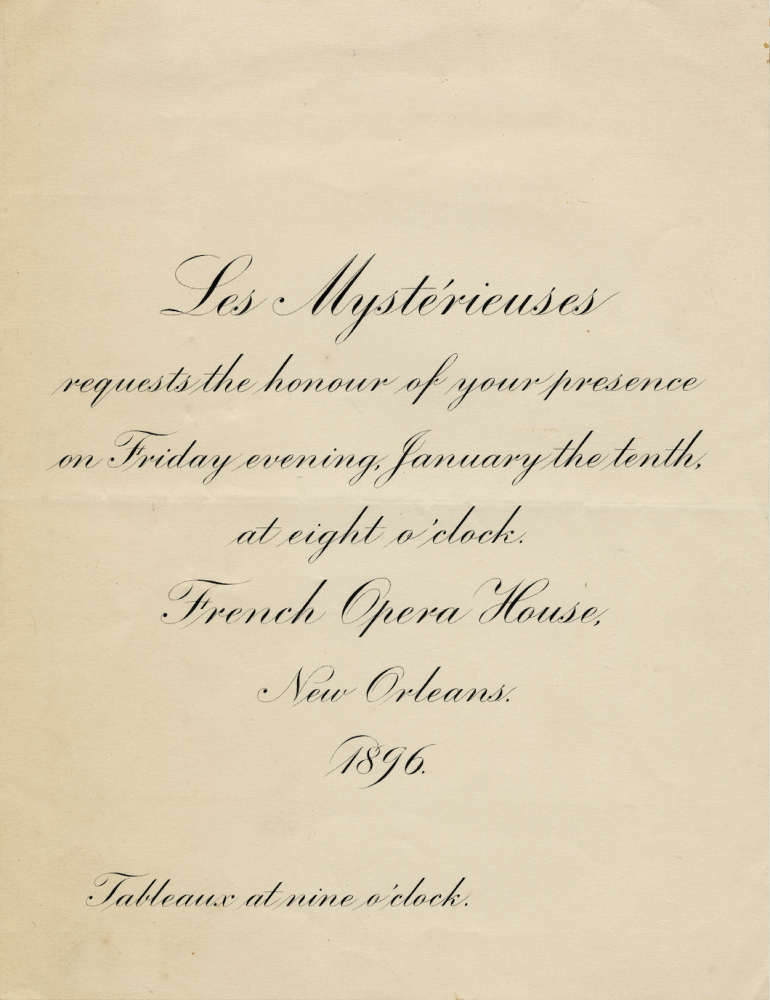

In 1896 several local women took advantage of leap-year traditions that allowed women to court men and upended the Carnival status quo. They formed the first all-women krewe, Les Mystérieuses, and reversed conventional male-female roles: at the ball, the man serving as king was put on display at the queen’s elbow, and male guests were required to wait for a callout from female krewe members in order to dance.

Calligraphy invitation to the inaugural ball of the first all-women Carnival krewe, Les Mystérieuses (THNOC, 1987.60)

Les Mystérieuses held its second and final ball in 1900, but in the years since a number of all-women krewes have continued to revamp Carnival. In 1941 the Krewe of Venus made history as the first women’s krewe to hold a parade, but it was met with disdain by many bystanders, who threw rotten vegetables at the floats. Carnival festivities were cancelled during World War II, but after it ended Venus returned to the streets. In 1949 the Krewe of Iris became the first women’s krewe to have its ball televised, and it held its first parade in 1959. Women’s krewes have proliferated in recent years, and their parades can be seen in the streets day and night throughout the Carnival season. —Cecilia Hock

This portrait of Iris Captain Irma Mellaney Strode, made in the mid-1950s, evokes the whirlwind gaity of Carnival time. (THNOC, gift of Joy B. Oswald, 2003.0108.1)

What happens to all the beads that don’t get caught?

All parading krewes, whether walking or riding, participate in the tradition of tossing trinkets and treats to crowds lining the parade routes of New Orleans. Anybody who has lined up to catch a “throw” can relate to the elation of catching a prize and the disappointment when it is missed. Throws have come a long way from the sweets of the late 19th century and glass beads of the early 20th century. Shining, blinking, plastic confections now abound, and as parades have increased in volume and spectacle, so have the mass-produced throws that fly from floats. One estimate put the weight of all throws shipped to New Orleans for Carnival-time disbursement at 25 million pounds.

What becomes of the plastic beads, cups, and assorted souvenirs that land in the streets unclaimed? The sheer volume of uncaught, unloved, and unwanted items regularly results in a mountain of debris that clogs the city’s crucial drainage system. In 2018 New Orleans removed 46 tons of throws trapped in the street drains within just five blocks of the main parade route. In addition, the beads themselves are coated with a wide variety of toxic substances such as arsenic, bromine, cadmium, and lead, which have been shown to leach into the soil.

The inventiveness and variety of handmade, signature throws defies description. Where but in New Orleans can one leave a parade with a sequined toilet plunger, a glittered brassiere, or a painted coconut? Shoes, wine corks, and roller-skate wheels are all subject to a krewe member’s imagination and carftiness, and few, if any, will wind up in the city’s catch basins! (Photograph courtesy of Kurt Owens)

There are alternatives to this annual glut of plastic beads. In combination with efforts to create sustainable throws and recycle plastic beads, parades are increasingly emphasizing “signature throws,” like glittered high-heeled shoes, feathered toilet plungers, beaded goblets, sequined sunglasses, ornately trimmed “grails,” and other handmade treasures produced in smaller quantities that are less likely to get ditched. The individuals who spend their year preparing these throws to be bestowed on the crowds can help New Orleans host a cleaner Carnival. —Kurt Owens