The water management system of New Orleans as we know it today has its roots in the response to the yellow fever epidemics that plagued the city for much of the 19th century. The period between the deadly yellow fever outbreak of 1878, which killed 4,000 people in New Orleans, and the discovery of the cause of the disease, in 1900, saw huge changes in the infrastructure surrounding drinking water and waste management.

Before the 20th century, the pedestrian was often confronted with offensive sights and smells, and in the years after the Civil War, New Orleans was one of the largest, smelliest, and deadliest cities in the United States. The city’s gutters, drainage canals, and streets—80 percent of which were unpaved in 1880—were littered with refuse, including garbage, food waste, and human and animal waste. Dirty, stagnant water could be found everywhere. Although the Department of Public Works was responsible for maintaining drainage, the lack of elevation inside the city meant that water had nowhere to go, and workers cleaned the gutters and canals by shoveling muck onto the streets, only to have it wash back during the next rain.

A cart driver at the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition is stuck in the mud in today’s Audubon Park. About 80 percent of New Orleans streets were unpaved in 1880. (THNOC, 1982.127.215)

By 1880 most big cities had installed some sort of sewerage system, but New Orleans still depended almost entirely on privies. Even houses and commercial buildings with the luxury of plumbing had to connect pipes to a privy or a gutter. Drinking water came from cisterns because well water was unsanitary, and city water from the New Orleans Waterworks Co. was dispensed straight from the Mississippi River. These water sources could easily become contaminated, leading to a host of gastrointestinal illnesses and, though it was not understood at the time, swift transmission of diseases such as dysentery, cholera, typhoid, and yellow fever.

New Orleans was a city of epidemics, and yellow fever was the worst, with outbreaks occurring almost annually after 1825. It was thought to be caused by miasma—humid air acting on filthy, undrained soil. The theory led residents to burn tar and shoot cannons into the air as preventative measures to “purify” it. Another idea, known as importation theory, held that the disease was spread by contact with individuals who came to the city aboard ships and railway systems. This belief led to strong anti-immigrant rhetoric and an insistence that locals were unaffected.

Mosquitos, which were discovered at the turn of the 20th century to be the actual vectors of transmission, found a perfect breeding ground in the city’s haphazard drainage system. But in the 19th century, these misconceptions meant that the real problem went unnoticed while the disease returned again and again during the hot summer months.

Street-side drainage gutters, like the one in this image, were littered with refuse, and dirty stagnant water could be found everywhere. (THNOC, 1982.127.177)

Street-side drainage gutters, like the one in this image, were littered with refuse, and dirty stagnant water could be found everywhere. (THNOC, 1982.127.177)

Enormous strides were made nationally in city services after the Civil War, but in New Orleans these changes did not come easily. Topography and climate made improvements expensive; city government was often mismanaged, with little money to spare; and the public remained largely unconcerned about the state of sanitation. One report said that "insalubrity was flatly denied, or disbelieved," and many people maintained "the nonexistence of the most dreadful evils."

In 1878 the community was shocked out of its lethargy when a devastating yellow fever epidemic originated in New Orleans and spread as far as Memphis, killing almost 20,000 people across the Mississippi River valley. Upriver towns and neighboring Gulf Coast cities like Mobile shut down all travel to and from New Orleans, closing trade with the city at the first hint of disease.

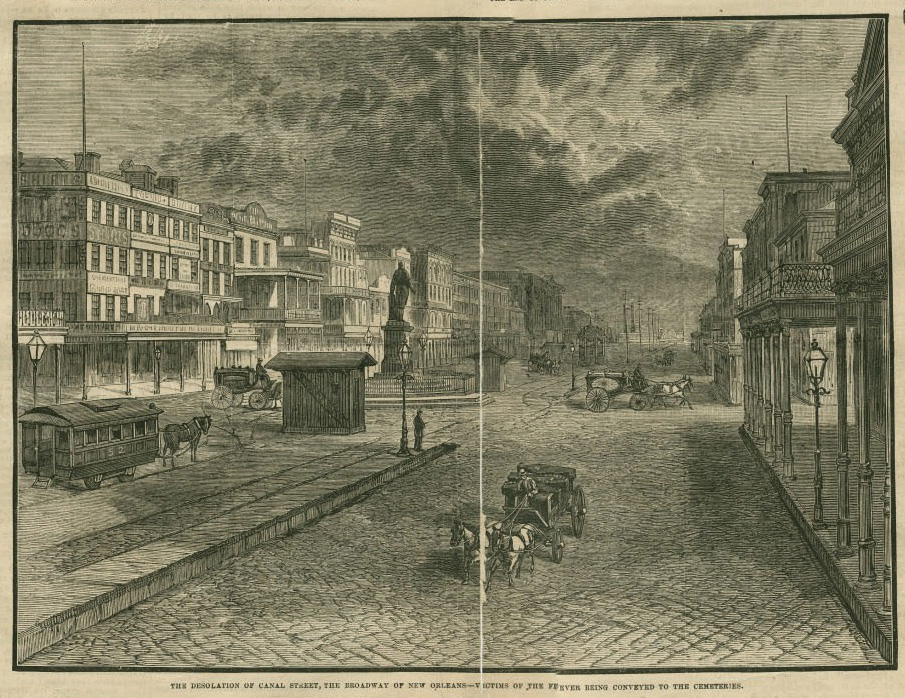

A drawing from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper depicts an empty Canal Street—save for the "victims of the fever being conveyed to the cemeteries"—during the 1878 outbreak of yellow fever, which killed over 4,000 people in New Orleans. (THNOC, 1981.216 i–xii)

A drawing from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper depicts an empty Canal Street—save for the "victims of the fever being conveyed to the cemeteries"—during the 1878 outbreak of yellow fever, which killed over 4,000 people in New Orleans. (THNOC, 1981.216 i–xii)

The economic impact of quarantine, which included disruptions to shipping and local commerce, moved New Orleans’ business class to find a way to stop the disease from returning. The Board of Health and the Howard Association, both of which were formed to deal with earlier bouts of yellow fever, had for years been trying to educate the public about the city’s shameful sanitation condition. Now they were joined by business and social leaders demanding change.

Some large businesses, such as D. H. Holmes and the St. Charles Hotel, constructed their own sewer lines to the river, while prominent New Orleanians formed organizations to decide how to solve the problems of the rest of the city. Their answers ranged from cleaning up the gutters to cleaning up the government. However, the general public clung to the theories of miasma and importation as to how the disease spread and remained unaware of the connection to sanitation, prompting most of the groups to disband.

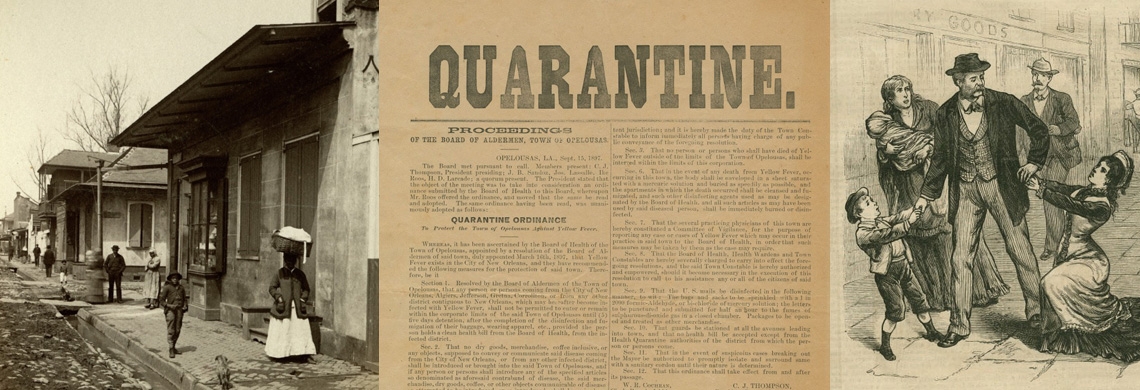

A broadside from Opelousas, Louisiana, outlines a quarantine on travelers and goods from New Orleans during the 1897 outbreak of yellow fever. (THNOC, 2001-259-RL.1)

A broadside from Opelousas, Louisiana, outlines a quarantine on travelers and goods from New Orleans during the 1897 outbreak of yellow fever. (THNOC, 2001-259-RL.1)

One group that survived was the Auxiliary Sanitary Association, which formed in 1879 and was financed almost entirely by private contributions from the city’s moneyed elite. (Additional contributions were roused when the Times threatened to print the names of wealthy people who had failed to contribute.) The association improved drainage canals, donated garbage barges to the city, and repaired city-owned equipment. Its most successful endeavor was a system of gutter flushing that cleaned up many streets.

Throughout the 1880s there were relatively few deaths attributable to yellow fever. Consequently, there were several failed voter initiatives to secure funding to improve water infrastructure. Beginning in 1884 the city hosted the World’s Cotton Centennial and Exposition in the well-drained area of Carrollton, hiding the controversial gutters from international visitors. That same year the city also hosted a sanitation conference for members of the state Board of Health and other public health representatives from the Gulf Coast region, where they made commitments to prevent the spread of contagious disease, including discussions of how to enforce a multistate quarantine and increasing resources for municipal sanitation.

A view of a crowded Canal Street in the 1880s includes D.H. Holmes, which installed its own sewer line to the river. (THNOC, 1974.25.8.114)

A view of a crowded Canal Street in the 1880s includes D.H. Holmes, which installed its own sewer line to the river. (THNOC, 1974.25.8.114)

By the 1890s state and municipal efforts aligned with private enterprise and Progressive Era education surrounding public health. When yellow fever struck again in 1897 it killed almost 300 people, which was the highest death toll since 1878. Officials and the population alike were frightened into action, and in 1899 voters, encouraged by a group of Progressive reformers known as the Municipal Improvement Association, at last approved funds for a drainage and sewerage system that would permanently clean up the city.

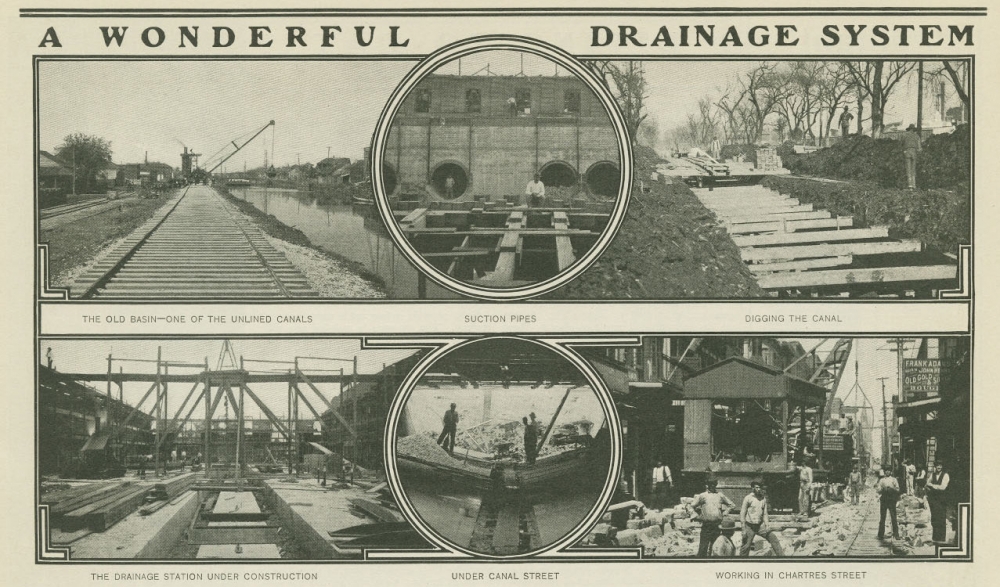

A Collier’s Weekly story from 1901 includes images of the new drainage system being installed, including underground sewerage lines and pumping stations. (THNOC, 1989.91.20 i–v)

A Collier’s Weekly story from 1901 includes images of the new drainage system being installed, including underground sewerage lines and pumping stations. (THNOC, 1989.91.20 i–v)

In 1902 the new Sewerage and Water Board began drainage work that would forever change the landscape of New Orleans. A system of subsurface piping was installed to replace the gutters, a water purification plant was built in Carrollton, and three pumping stations were installed. The pumps carried standing water into the city’s existing outflow canals, which emptied sewerage into the river and water drainage into the lake. Over the next two decades, these improvements allowed the city to drain the “backswamp” and open new areas for settlement. By 1923, the Sewerage and Water Board claimed that 92 percent of the city’s population had access to sewer lines.

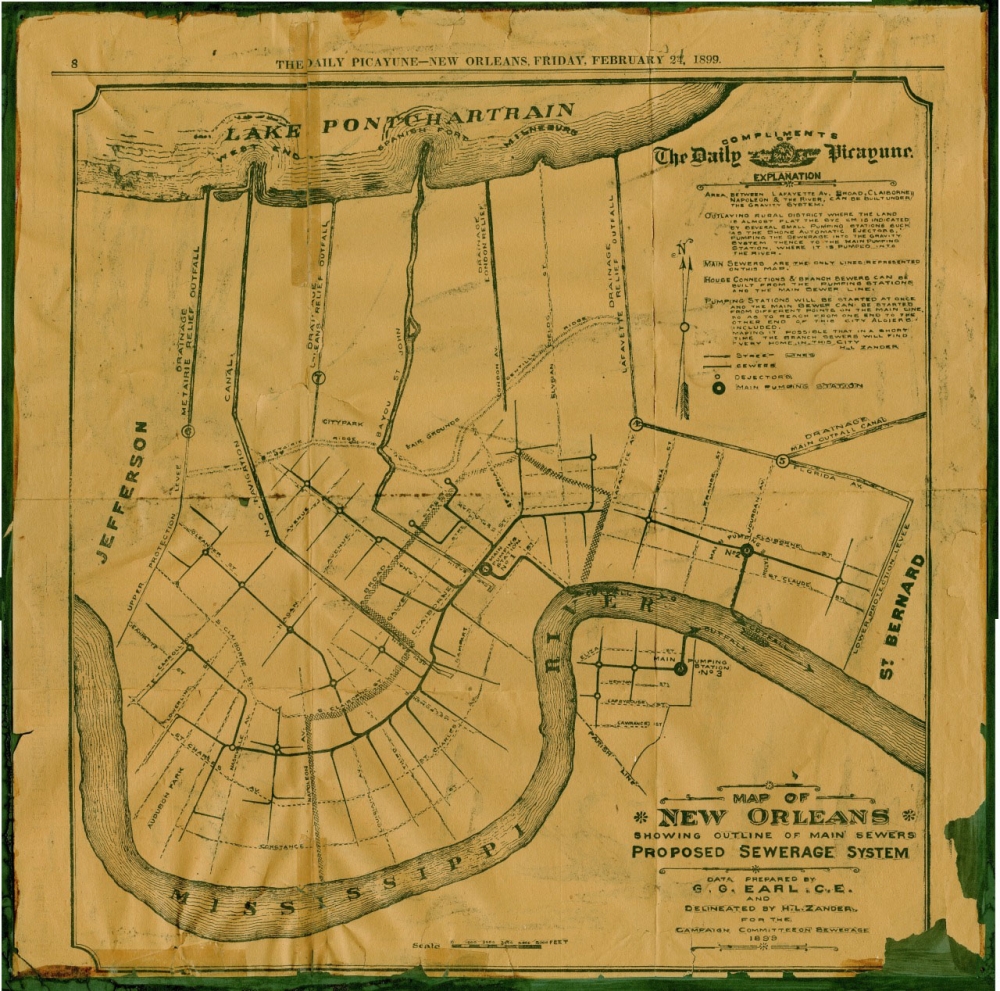

A map, published in the Daily Picayune in 1899, shows the outline of the proposed sewerage system, much of which remains in use today. (THNOC, gift of Don Wilson, 2003.0190)

A map, published in the Daily Picayune in 1899, shows the outline of the proposed sewerage system, much of which remains in use today. (THNOC, gift of Don Wilson, 2003.0190)

When yellow fever broke out again in New Orleans in 1905, city leaders were armed with the knowledge that the disease was spread by mosquitos, thanks to the discovery made by US Army researchers in Cuba five years earlier. Citizens were ordered to eliminate any stagnant water and to cover their cisterns, thus preventing breeding areas for mosquitoes. A quarantine was also imposed to keep people in their homes. It marked the last outbreak of yellow fever on the North American continent. The time to call New Orleans America’s most plague-ridden city was over.

A version of this article, written by John Magill, appeared in the Winter 1986 edition of The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly. The story has been enhanced with new research by Emily Perkins, curatorial cataloger.