Letters provide us with a window into another world. They connect us with the past in a way that many history books cannot, drawing us into another realm and revealing the nitty-gritty aspects of life.

Among the most popular resources at The Historic New Orleans Collection are sets of family papers, often rich in detail and emotion. The O’Regan collection, acquired a decade ago, sheds light on the immigrant experience in New Orleans while drawing us into the lives of six siblings from Ireland.

Through letters, photographs, and scrapbooks, we learn about the business prospects, educational opportunities, poverty, war, and illnesses that immigrants to the city encountered in the mid-19th century.

When Michael O’Regan, a physician and the eldest of the siblings, left Ireland in June of 1842 to seek a better future in New Orleans, his family was in dire financial straits as a result of his father’s misdeeds. Despite optimistic assurances to his mother that “we will see brighter days yet,” Michael faced seemingly insurmountable barriers in New Orleans. He suffered from a series of financial setbacks and a devastating bout with yellow fever. He wrote of his disillusionment with American medical practitioners who were too motivated by “the almighty dollar.”

A view of the port of New Orleans, made around the time that Michael O’Regan arrived from Ireland. (THNOC, 1950.3)

Despite the hardships that their brother endured, five of Michael’s thirteen siblings had followed him to New Orleans by the early 1850s—Terence, Charles, William, James, and Alice. In a series of letters between the New Orleans O’Regans and their family members in Ireland, particularly siblings John and Ellen, the family’s story unfolds. John, who served as the archdeacon of Kildare from 1862 to 1879, often provided financial support to the family.

The O’Regans were part of a mid-19th century influx of Irish immigrants to New Orleans. Between 1842 and 1864, 110,000 Irish entered the port, making it the second largest Irish immigration site in the United States, second only to New York. The majority of these immigrants left New Orleans for the Midwest. Because few were farmers, they congregated in cities and towns, moving constantly in search of better jobs.

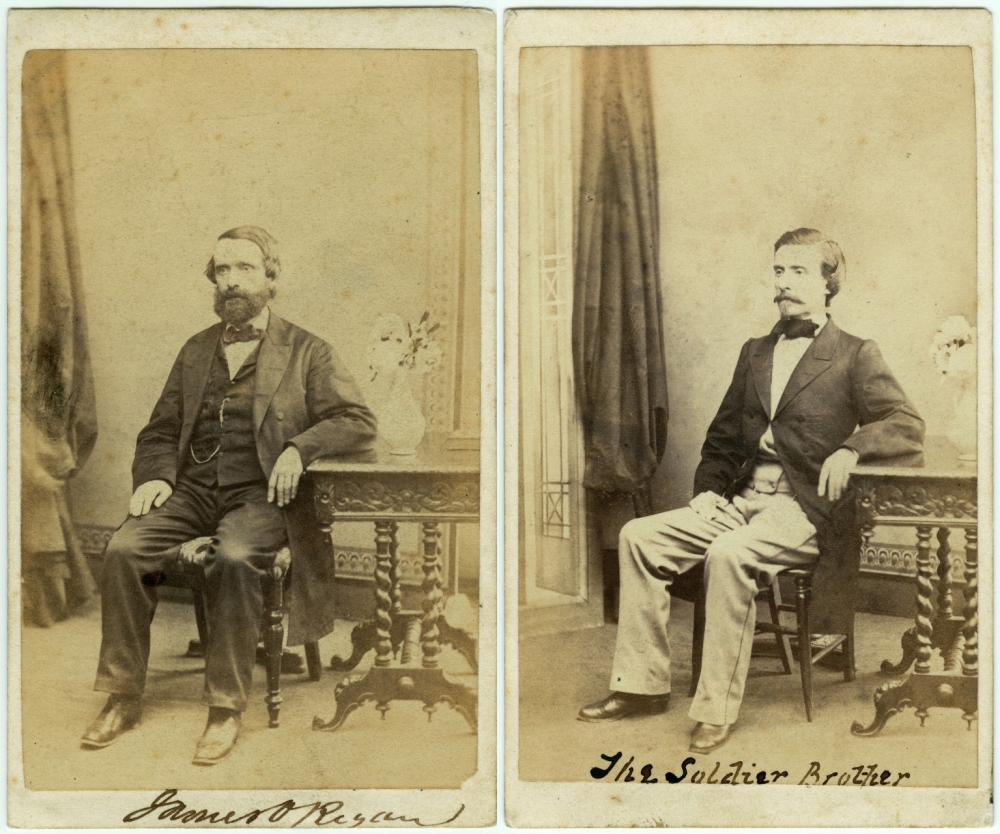

Two photographs show James (left) and Willie (right) O’Regan in 1863. (THNOC, 2009.0159.2, .3)

Charles O’Regan was the first of the O’Regan clan to leave New Orleans. In a letter to Ellen in February 1853, he wrote, “When you next hear from me you and all will have cause to be proud of me—until then I only ask your prayers and the charity of silence.” His fate is unknown, and it appears that the family never heard from him again. “No trace or tidings of him ever reached here since his departure,” observed Terence in an 1887 letter to John.

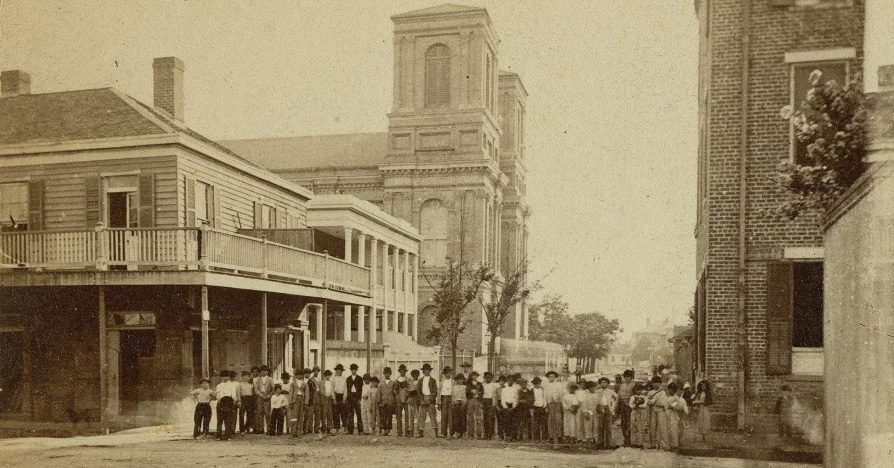

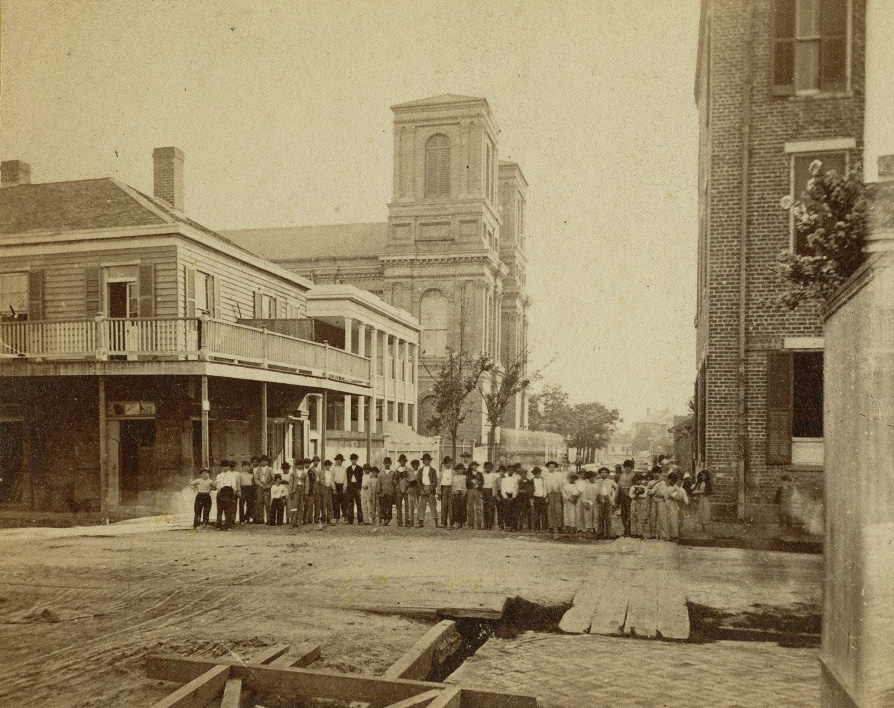

According to the 1850 census, the first to note country of birth, there were between 20,000 and 22,000 Irish living in New Orleans. They settled in neighborhoods across the city, where they built Catholic churches and established benevolent societies. The 1850 and 1860 censuses reveal that while most labored in occupations requiring little skill, some earned livings as clerks, cotton samplers, grocers, bakers, masons, and contractors.

An image taken shortly after the Civil War shows the St. Alphonsus Irish Church in the background. Irish immigrants settled in neighborhoods across the city, where they built churches and formed benevolent societies. See the current location on Contsance Street in Google Maps. (THNOC, 1995.26.2 i)

The O’Regans were members of this educated class, but faced discrimination all the same. In June 1853, Alice O’Regan, who attended Madame Deron’s exclusive St. Louis Street academy, wrote, “It would never do in a Creole school to say you were Irish, there is something in the very sound of the word connected in their ideas with vulgarity, it often amuses me to hear the way they speak about my country people, little they know how near they have one of the despised race.”

The prejudice that she experienced at Madame Deron’s academy was the least of Alice’s woes. Her letters relate her struggles with adapting to a new climate and the high cost of living. She was also in a state of poor health, having “lost all the front teeth in her upper jaw” by 1853. In October 1854, Alice O’Regan, just 23 years old, lost her life to yellow fever.

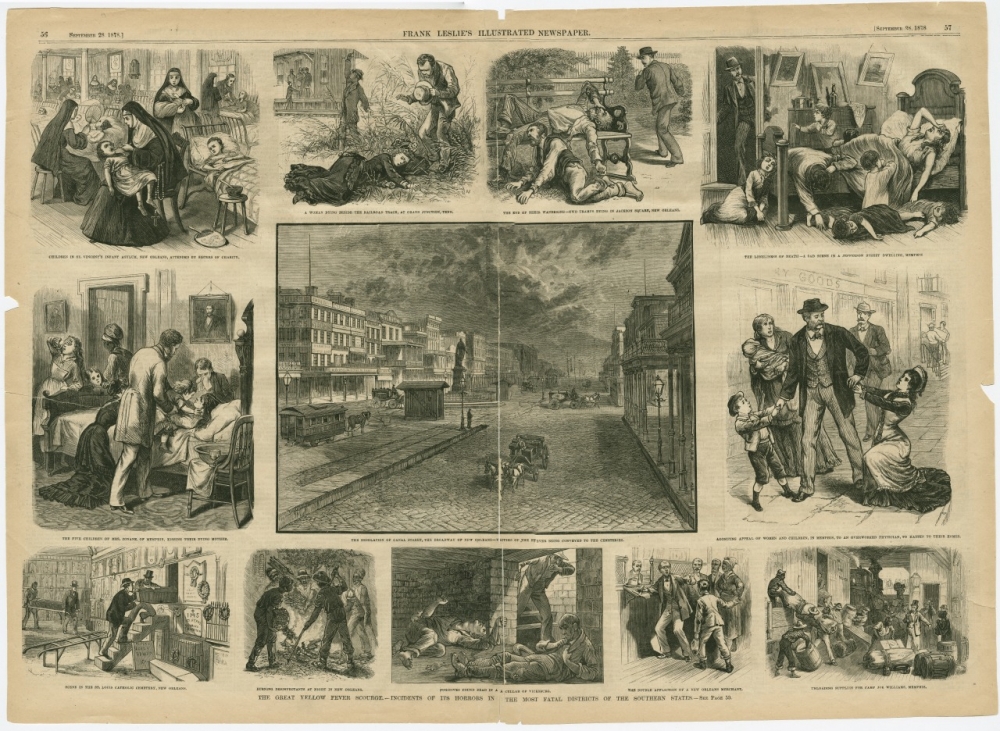

An 1873 broadside shows the effects of yellow fever, the disease that, in 1854, killed Alice O’Regan. In 1853, more than 8,500 people in the city died of the disease. (THNOC, 1981.216 i-xii)

Although his letters home were teeming with optimism, Michael O’Regan eventually gave up on New Orleans and returned to Ireland in 1855, less than a year after his sister’s death. He died there shortly before Christmas in 1859.

James O’Regan, deaf and mute, initially fared better than Michael and Alice. He worked as an engraver in New Orleans, Atlanta, and New York City. But his success was not necessarily a cause for family celebration. In Terence’s words, James lived “by himself & in himself, & for himself”—an assessment possibly colored by a recent family dispute over the cost of Alice’s education. Family letters place James in New York with a wife and child in 1859, but by the time he died, in 1884, James had returned to New Orleans.

In an 1887 letter to John explaining the whereabouts of the brothers remaining in the States, Terence wrote, “James & Self were, for nearly 6 weeks, patients in the Charity-Hospital.— stricken down by Typhoid fever—(caused by exposure & want of food,) both of us were brought very low…but James never rallied from the effect of this attack,—his reason was shattered,—he passed away.”

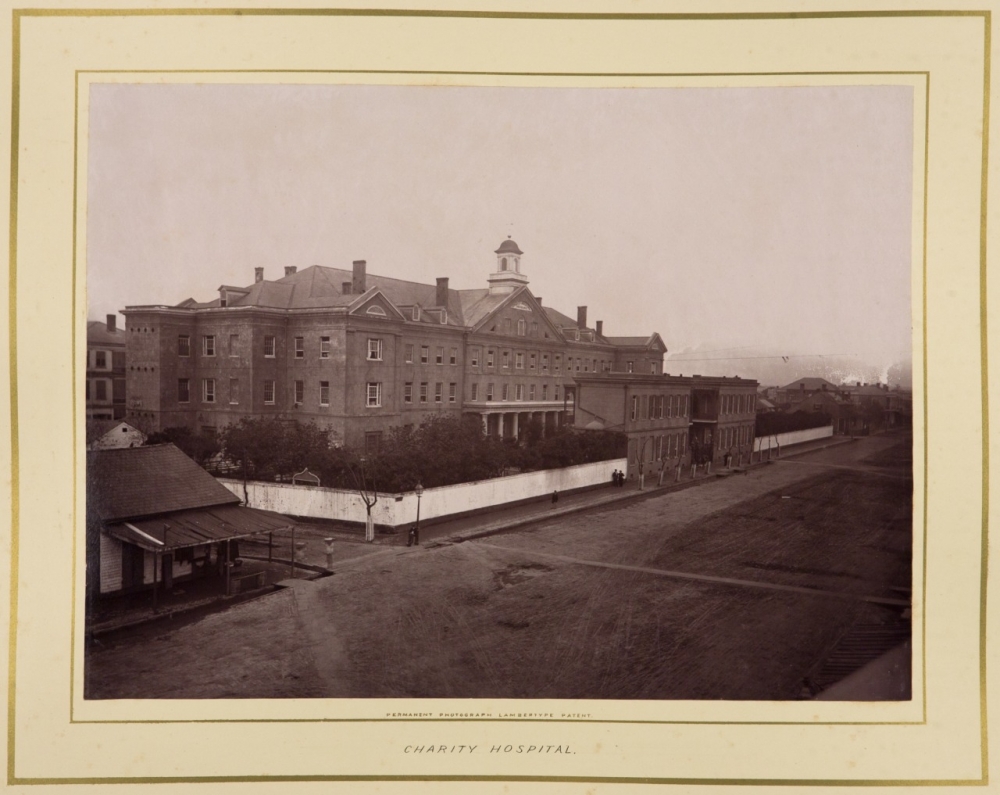

James O’Regan died at Charity Hospital after fighting Typhoid fever. The hospital is shown here in 1867. (Courtesy of Fritz A. Grobien)

William “Willie” O’Regan, an optimist like his brother Michael, plotted one scheme after another in hopes of forging a better life. He found himself swept up in the tide of war, and in June of 1861 he related his reasons for taking up arms for the Confederacy to his sister Ellen: “Louisiana called on her sons for aid. I know my duty and giving up everything that was dear to me, I answered her call & became a soldier…. I am not going to throw my life away recklessly but I am going to do my duty.”

According to his service record, Willie was discharged on April 15, 1862 (no reason is given), at which point he headed to Liverpool. In 1864 he was granted permission to return to the Confederacy via Baton Rouge. From there he attempted to enter New Orleans, then under Federal control, but was captured and imprisoned at the blockaded port. The family’s concern for Willie is apparent in the flurry of letters Terence, John, and Ellen exchanged with Federal authorities and the British consulate. Their efforts successfully secured Willie’s release in March 1865.

An 1861 map shows the Union blockade off the coast of Louisiana. Former Confederate soldier Willie O’Regan was caught and imprisoned by Union forces upon trying to enter New Orleans in 1864. (THNOC, 1956.50)

Despite his wartime experiences and his subsequent imprisonment, Willie remained determined to succeed in New Orleans. In November 1865 he wrote to John that he “returned to New Orleans broken in all but spirit.” Regrettably, Willie staked his hopes on a failed cotton venture. Faced with a mountain of debt, he wrote to Ellen in June of 1866, “This is the ending of all my hopes.” It remains unknown if Willie was able to recover from the devastating financial blow. He is not mentioned again until Terence’s 1887 letter stating that “the last heard from him,—he was in New Mexico, how engaged, or in what part of that country he was, I could never learn.”

Terence O’Regan, who had worked for a merchant and for a time as a clerk, was financially devastated by the Civil War. He wrote in its aftermath that he “found it hard to even get food for his family.” His failing health and eyesight did not help matters. By 1887 he was forced to seek financial assistance from his brother John.

Poverty, pride, disease, and death left the O’Regan family scattered across two continents, but as the letters they left behind reflect, their devotion to one another remained intact.

Terrence Fitzmorris, adjunct instructor, history department, Tulane University, provided information about the Irish in New Orleans for this story. A version of this article originally appeared in the Winter 2010 edition of The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly. Access to THNOC’s manuscript holdings is available at the Williams Research Center, 410 Chartres Street. No appointment is necessary.

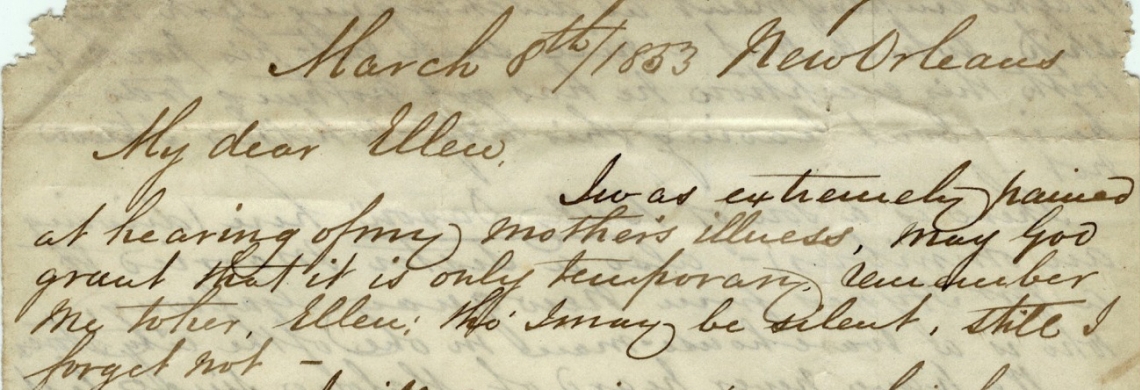

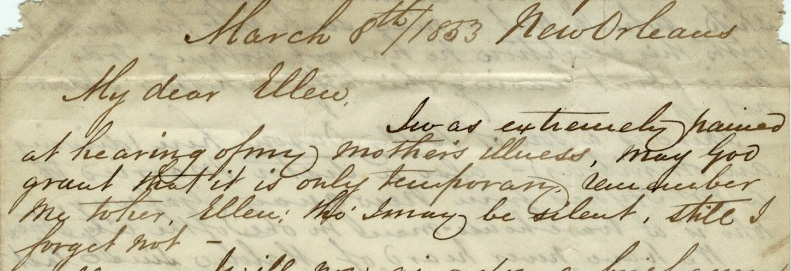

Cover image: Letter to Ellen O'Regan from Terence O'Regan (detail); 1853 March 8. (THNOC, 2009.0159.5)

Cover image: Letter to Ellen O'Regan from Terence O'Regan (detail); 1853 March 8. (THNOC, 2009.0159.5)