The 1951 film of Tennessee Williams’s New Orleans–set A Streetcar Named Desire won multiple Academy Awards and is considered a landmark of American cinema. To prepare for the August 24, 2020, #NolaMovieNight group re-watch of the film, First Draft returned to local dialect coach and acting teacher Francine Segal for insight into the film’s accents (always of interest to New Orleanians) and acting styles. Segal provided a similar service for our May 2020 #NolaMovieNight premiere, 1986’s The Big Easy.

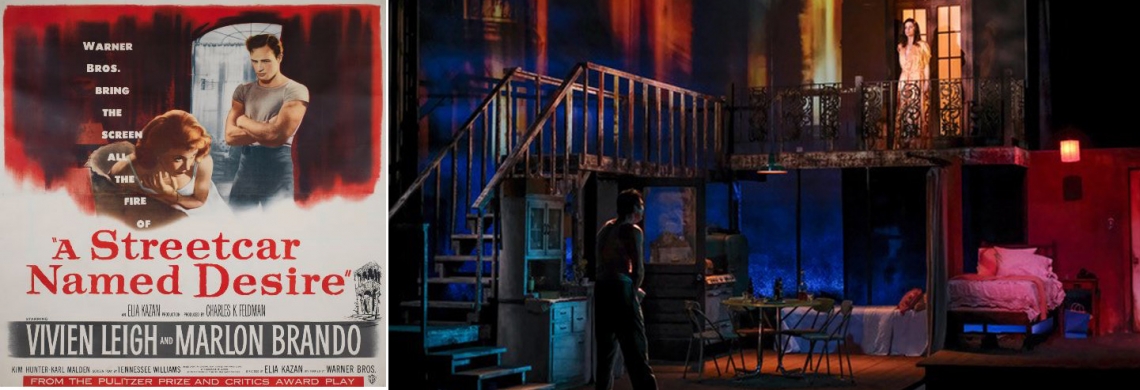

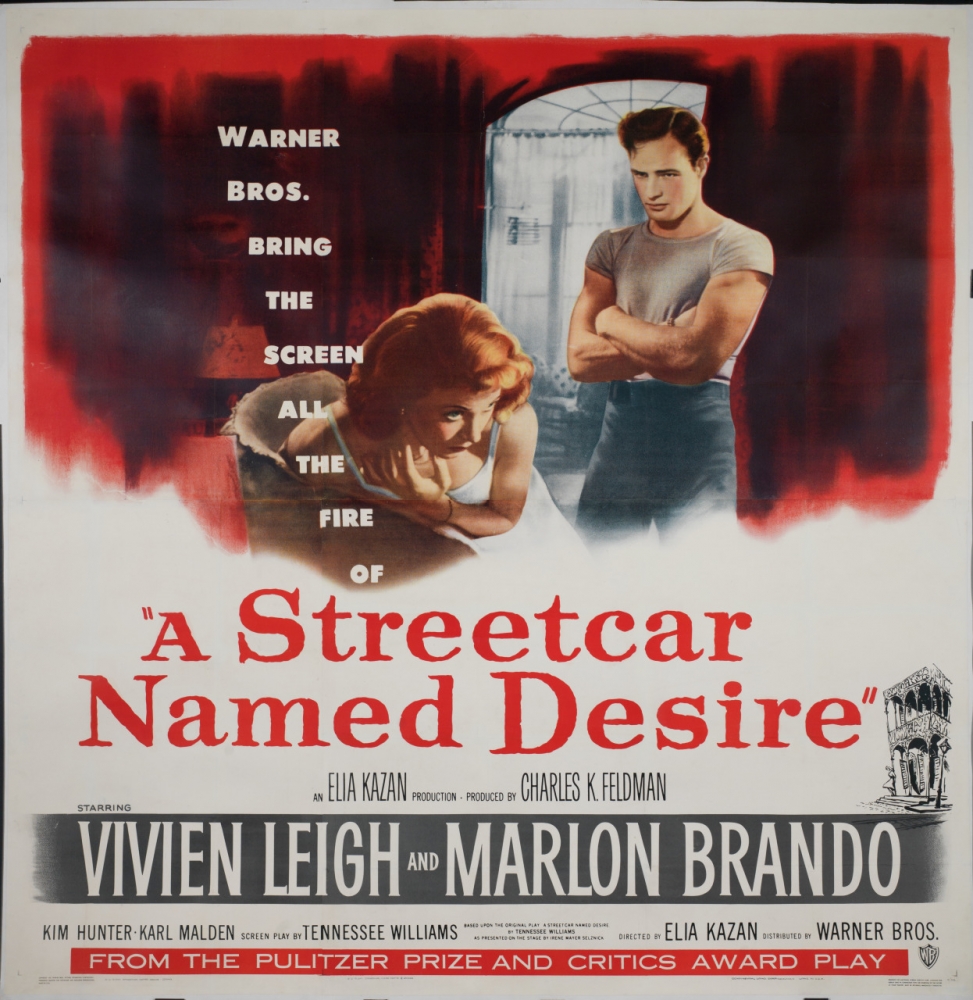

Large six-sheet poster for the film A Streetcar Named Desire featuring an image of a scene with Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh. (The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection at THNOC, 2008.0029.1)

Large six-sheet poster for the film A Streetcar Named Desire featuring an image of a scene with Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh. (The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection at THNOC, 2008.0029.1)

Q: What are the acting styles revealed in the film version of Streetcar?

A: There is a contrast in acting styles in Elia Kazan’s film version of Streetcar because Vivien Leigh’s British stage technique was inconsistent with the more natural interpretations played by the other actors in the film. Leigh was classically trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in England. The old-world stage techniques paid attention to physicality in creating a character from the outside to reveal the character within.

Leigh played Blanche in the British stage version of Streetcar directed by her husband, Laurence Olivier, before she re-created the role in Kazan’s screen adaptation. Her stagey, over-the-top style does not serve her well with today’s audiences. I believe that Leigh chose to play Blanche as an aging coquette, and many of her repeated acting choices were sexual flirtations revealing an aging version of Scarlett O’Hara. Tennessee’s dialogue for Blanche is powerfully written poetry which does not need to be embellished with neon lights.

Vivien Leigh is shown on set during the filming of A Streetcar Named Desire. (The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection at THNOC, 2001-10-L.1377)

Kazan, as well as Marlon Brando and Karl Malden, were products of the Method school of acting taught by Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio, which grew out of the Group Theatre’s exploration of Konstantin Stanislavski’s system of acting. This new acting Method—using affective memory, animal work, and sense memory techniques—encouraged actors to dig deep into their experiences and imaginations to bring up the specific raw emotions needed to serve as undercarriage for the actions they chose to play in a scene. Long rehearsal periods with deep explorations into the psyche of the characters were used to create a role. Brando’s introspective technique helped to make him electrically alive every moment of the film, and Malden’s and Hunter’s performances were unprocessed and believable because Kazan, also a teacher at the Actors Studio, directed them in this same style.

Leigh’s traditional training for the theatre focused on the use of the body to express character and action. Classically trained actors were taught how to use their voices effectively for the language of Shakespeare and stage projection. Film acting requires a different skill set of focus, concentration, and stillness, which is in congruence with the training of the Actor’s Studio. So, I am not selling Leigh short with respect to her acting chops. However, I believe that two distinctly different acting styles in Streetcar are evident in this highly acclaimed film.

Was there authenticity in the dialects used in the Streetcar film, set in 1947 New Orleans?

New Orleans dialects have more diversity in sound and vernaculars than most cities in the United States. Louisiana accents are rooted in French and other European immigrants who came to this robust port in the 19th century. Tennessee Williams, who lived many years in the Vieux Carré, heard the mélange of different sounds coming from inhabitants of the French Quarter and suggested their speech patterns in the rhythms of the dialogue he wrote for his characters.

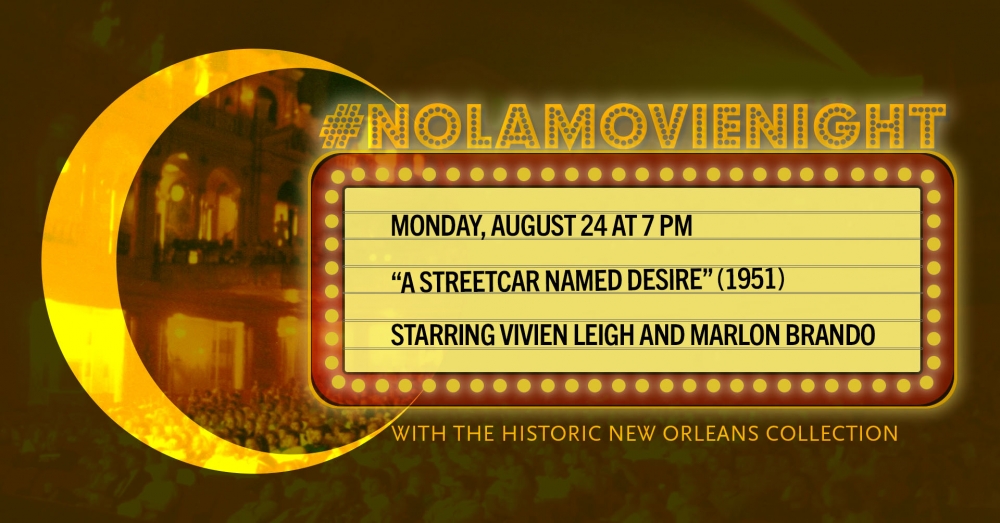

The Desire streetcar route served the shopping areas along Royal and Canal streets and the nightclubs on Bourbon Street. The route ceased operation in 1948, months after A Streetcar Named Desire premiered on Broadway on December 3, 1947. (THNOC, 1999.44.3)

The Desire streetcar route served the shopping areas along Royal and Canal streets and the nightclubs on Bourbon Street. The route ceased operation in 1948, months after A Streetcar Named Desire premiered on Broadway on December 3, 1947. (THNOC, 1999.44.3)

In the play, there are many references to Stanley’s Polish heritage and his WWII army experience. Brando was believable in his accent because it did not sound Southern, and in this case worked for his character. It is always a big mistake if an actor tries to imitate Brando’s own distinctive accent in re-creating the role.

However, the character of Blanche is from Laurel, Mississippi, in which a Southern sound, including vowel elongation into diphthongs and softer Rs is appropriate. Leigh played Blanche with a flowery drawl that was more palatable in 1951 when the movie came out. I personally have observed that many actresses still believe today that Leigh’s drippy accent was the quintessential New Orleans accent. Her dialect has been misused for decades by many actresses in film and on stage.

Hearing Streetcar through a 2020 speaker gives more authenticity to the dialects of Karl Malden as Mitch and Kim Hunter as Stella because they were more natural in their speech, using some subtle Southern sounds. A genuine dialect comes out of the acting. It is not a bandage put on top of the acting. These actors were successful because they played their actions truthfully in the moment, and their accents came out of their acting choices.

How heavily does the film hang over any theater production of Streetcar, and how does that challenge the actors to create roles that are not influenced by the indelible performances of Brando, Leigh, Malden, and Hunter?

Research on a role starts with Williams’s language for the specific character, and the worst possible preparation is to look at the film version. That said, it is still difficult to shake a lasting impression of the characters from the film even if one saw the film version a long time ago. When embarking on a role, it is the job of the actor to analyze the text and find the objectives and actions of the character, the obstacles, understand the relationships, and the time period of the play.

An image captures a 2018 production of A Streetcar Named Desire at Le Petit Theatre. (Photograph by Brittany Werner)

An image captures a 2018 production of A Streetcar Named Desire at Le Petit Theatre. (Photograph by Brittany Werner)

I have seen over 30 stage productions of Streetcar in Europe and different parts of the United States. In my opinion, some of the productions of Streetcar produced in New Orleans were among the truest and most authentic in executing Williams’s vision. I asked some local artists involved with these shows to comment on how they avoided falling into the actor’s trap of imitating the luminaries from the film version.

A 1990 production of Streetcar at Le Petit Theatre, produced by Mike Arata and directed by John Grimsley, was charged with raw emotion. David Dahlgren (inset, photo by Laura Flannery), who played Mitch with integrity, comments here:

I never worried about imitating Karl Malden. He didn't have specific, easily imitated mannerisms and speech patterns like Brando and Leigh. I tried to get in touch with what drove Mitch. I thought, “Here I am, my life is a comfortable routine, the best years are behind me. I never achieved the married bliss (as I perceived it) of Stanley and Stella. Then along comes this elegant creature, (Blanche).” I immediately idealize her and see her as a savior from the ordinariness of my life. Maybe I can have what Stanley and Stella have, and more. From the moment I meet her, whether I'm in her company or not, I'm creating a fantasy future. I either ignore or fail to see any signs that something might be rotten in Denmark. The depth of my fantasy matches hers, although in a different direction. When I finally learn the "awful truth," my disappointment—and anger—is the classic example of one who sees his Last Big Chance crumble and vanish.

I never worried about imitating Karl Malden. He didn't have specific, easily imitated mannerisms and speech patterns like Brando and Leigh. I tried to get in touch with what drove Mitch. I thought, “Here I am, my life is a comfortable routine, the best years are behind me. I never achieved the married bliss (as I perceived it) of Stanley and Stella. Then along comes this elegant creature, (Blanche).” I immediately idealize her and see her as a savior from the ordinariness of my life. Maybe I can have what Stanley and Stella have, and more. From the moment I meet her, whether I'm in her company or not, I'm creating a fantasy future. I either ignore or fail to see any signs that something might be rotten in Denmark. The depth of my fantasy matches hers, although in a different direction. When I finally learn the "awful truth," my disappointment—and anger—is the classic example of one who sees his Last Big Chance crumble and vanish.

Southern Rep Theatre’s 2012 production of Streetcar was an environmental historical feast with street vendors and French Quarter sounds at Michalopoulous Studios near the 632 Elysian Fields address where Stella and Stanley actually live in the play. Aimée Hayes (inset, photo by Ride Hamilton), the current producing artistic director of Southern Rep, played a gentle, endangered Blanche of multiple colors. Aimée comments here:

This is what I know about Blanche: She is a woman who had a lively intellect, a romantic interest in art, poetry, music, and an exuberant desire for connection. Smashed sideways by ugly countless losses (all of those family members she tended to the grave) and circumstances of repeated betrayal both sexual and romantic, Blanche becomes hardened, wise to the weaknesses and betrayals of people; humans are treacherous in their emotional messiness and disregard for others. She attempts to gain something for herself—a little slice of safety and peace—using tactics she has gleaned during her tortuous time at the Tarantula Arms. Along the way she develops a wicked sense of humor and becomes a drunk.

This is what I know about Blanche: She is a woman who had a lively intellect, a romantic interest in art, poetry, music, and an exuberant desire for connection. Smashed sideways by ugly countless losses (all of those family members she tended to the grave) and circumstances of repeated betrayal both sexual and romantic, Blanche becomes hardened, wise to the weaknesses and betrayals of people; humans are treacherous in their emotional messiness and disregard for others. She attempts to gain something for herself—a little slice of safety and peace—using tactics she has gleaned during her tortuous time at the Tarantula Arms. Along the way she develops a wicked sense of humor and becomes a drunk.

An alcoholic's need for the next drink overpowers everything I imagined drinking like Blanche would see most of us pretty plastered. There is nothing poetic about it. This facet of her being was really my way in. The daily struggle of wanting oblivion while also maintaining a facade of Southern-bred gentility was key to my Blanche. I adored when her original self would come through—when she experienced beauty or felt like that gentle little girl again. Most of those moments are when she feels physically and psychically safe. Blanche stands in for anything we have ever treasured and then seen muddied and destroyed by the brutes of the world. I think Tennessee knew it was the risk every artist takes by living a public life. I also contend, for Blanche, the play ends happily, strolling down Elysian Fields on the arm of a handsome doctor. The past is obliterated; the present is white—sheets, nightgown, walls. Peace at last.”

Maxwell Williams (no relation to Tennessee) is the current artistic director of Le Petit Theatre, and directed a classically styled, compassionate 2018 production of Streetcar in which the poetry of Williams was highlighted through a 2020 lens, as the audience experienced the story through Blanche’s eyes. Maxwell comments:

Any time one takes on the challenge of grappling with an iconic play, there's a mental negotiation around how best to present the play in the immediate moment. That boils down to the question we ask in doing any play at a particular time: Why do this play now? It's especially tricky when you're working with a play as iconic as Streetcar, which lives in the popular imagination in many ways through Kazan's brilliant, moody, smoky film and the performances of the four main characters, which seemed to be based so strongly around the types and personalities of those actors. But the play in a live setting has the virtue, in my opinion, of being an almost operatic piece, aggressively dynamic.

It's not possible to do an imitation of Marlon Brando or of Vivien Leigh in that picture that aspires to be anything but a parody. So, we did what we try to do in all the work we create, which is to try to free ourselves from preconceived notions and approach the play as if it was new and we were fortunate enough to be doing it for the first time. Thus, we centered much more on Blanche, her desperation and her agency, than in the film, which set the standard for decades that Stanley is at the center of the play, which he is not, in my opinion. Your hope is always to approach a play with fresh eyes, because that's the experience you want to deliver to an audience—to surprise them with elements of a classic that they aren't anticipating.”

Tennessee Williams’s written play serves as a road map into his characters and their relationships during the time period of the play. This powerful writing can incite the imaginations of artists. An artist has license to create their own stamp on their role as long that they remain truthful to the intent and language in the play. A focus on the text of A Streetcar Named Desire in preparation for playing a role on stage can override an imitation of the film’s enduring performances.

Join us on Monday, August 24, 2020, at 7 p.m. for a group re-watch of A Streetcar Named Desire.