Three days before Christmas in 1718, Marie Grissot lay dying, giving her last will and testament. The 48-year-old maitresse sage-femme (master midwife) knew that “there is naught as certain as death and nothing more uncertain than the day and hour thereof,” and nowhere was this truer than the harsh home she had made for 14 years, in the fledging colonial capital of Mobile. Grissot had spent virtually all of those years as Louisiana’s sole midwife, bringing new lives and new hope into a settlement in dire need of both.

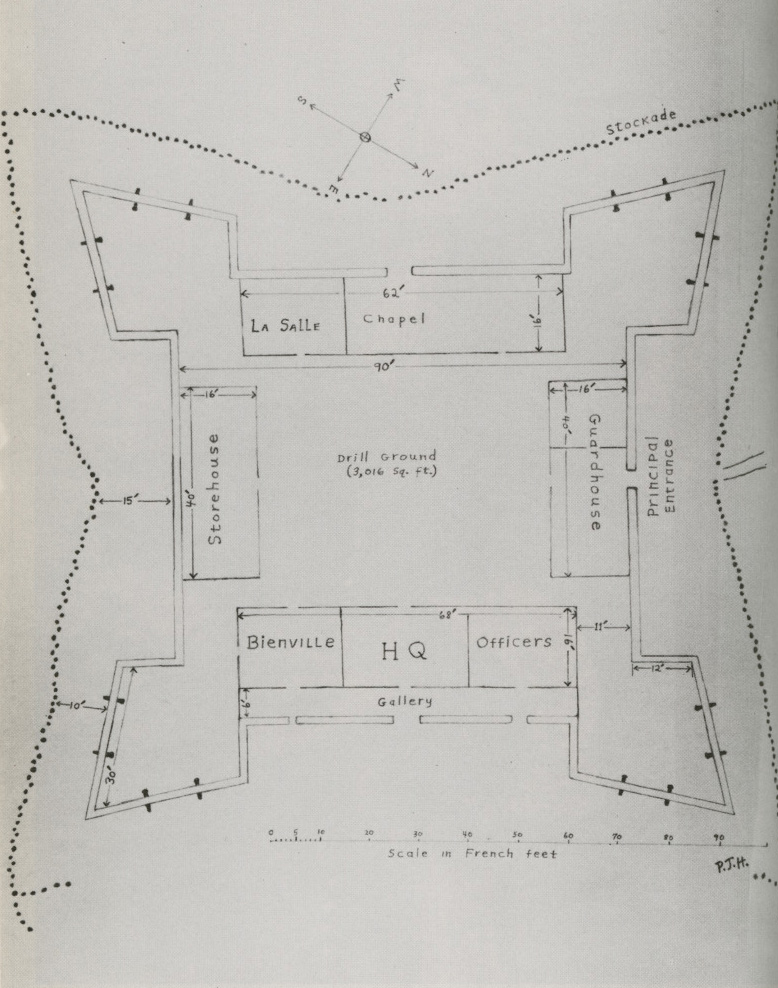

This sketch of Old Mobile in 1711 is from Peter J. Hamilton's history Mobile of the Five Flags (1913) and is based on colonial records of the settlement’s layout. Fort Louis can be seen in the foreground, on the bank of the Mobile River, with residential structures behind it to the left and right. (THNOC, 77-390-RL)

Settling her affairs, she declared herself a devoted Catholic, willed various sums of money to several people, and left the rest of her modest estate to her nephew. The will is formal and standard, with one exception: she took great pains to ensure that her heir’s father, André Pénigault, be “wholly excluded from her succession, without ever being able to pretend to anything whatever.”

Grissot’s bitterness toward Pénigault stemmed from a years-long feud with the young colony’s commandant and de facto ruler, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville. Grissot and Bienville had gone head-to-head during the desolate years of Mobile’s early existence, and Pénigault, a carpenter in the colony who had married Grissot’s relative, walked away from the conflict with half of Grissot’s royal salary. It was an offense she took to her grave.

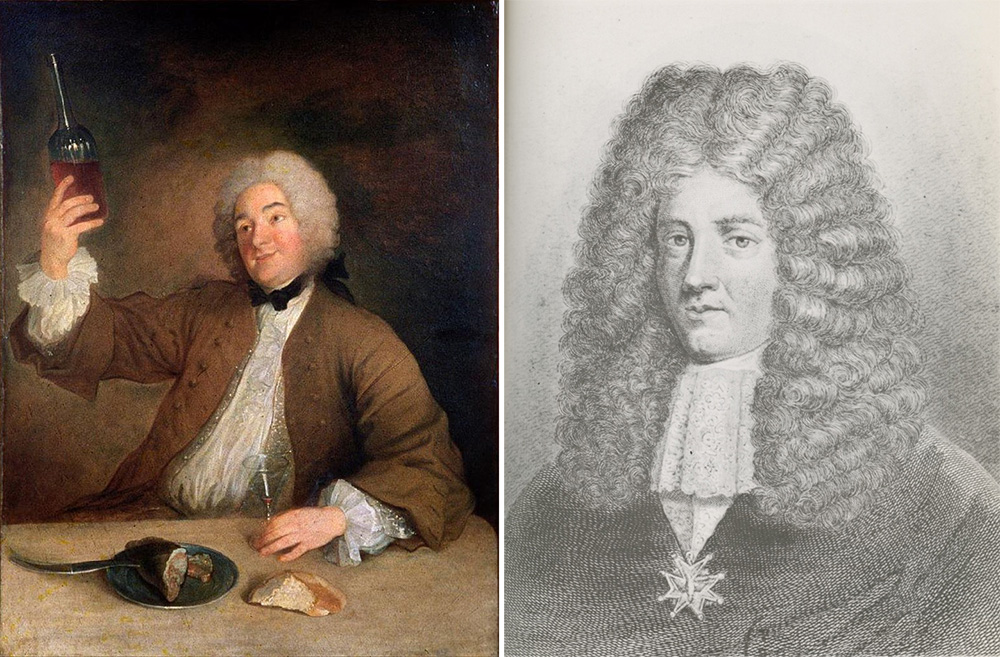

Bienville was only in his mid-20s when he served as commandant and de facto ruler of the young colonial capital at Mobile. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 1990.49)

On the surface, the Bienville-Grissot feud was a salary dispute: as royal midwife, Grissot was allotted 400 livres per year. This was a significant sum in as needy an environment as colonial Mobile, and the years leading up to and during the dispute were particularly desperate ones. The colony was cut off for long periods from supplies and support from France, which was busy hemorrhaging money on wars, and Bienville wanted to reapportion Grissot’s salary elsewhere. But the conflict also called into question the value of Grissot’s work, which centered women and babies. Bienville apparently decided that midwifery presented no appreciable benefit to the colony and attempted to take away her entire salary on the grounds that she was “useless for Louisiana,” according to a 1710 report.

Whether done out of desperation, political malice, misogyny, or a combination of all three, Bienville’s attack on Grissot ran counter to France’s official policies and stated goals for colonial development. Not only was a midwife like Grissot more than useless: the difficult, dangerous business of bearing children was of utmost importance to the young colony.

The Royal Midwife and the “Future Mothers of Louisiana”

In January 1704, Jérôme Phélypeaux, comte de Pontchartrain—the king’s top official in Versailles overseeing the affairs of the colony—wrote to Bienville that a special shipment would be headed to Louisiana. In addition to carrying supplies and soldiers, the Pélican was to bring 24 girls “of recognized and irreproachable virtue . . . to be married to the Canadians and others who have begun to make themselves homes on the Mobile in order that this colony may be firmly established.” The Pélican girls were “the future mothers of Louisiana,” writes Jay Higginbotham in his meticulous history Old Mobile: Fort Louis de la Louisiane, 1702–1711.

The 24 marriageable girls who arrived on the Pélican in 1704 were not the famed Casket Girls, who arrived in New Orleans 1721 (depicted here), but their reason for being sent to Louisiana was the same—to help populate the colony. (THNOC, 1974.25.10.40)

It had been five years since Pierre Le Moyne, sieur d’Iberville, had claimed a vast swath of North America for New France. New Orleans wasn’t even a glimmer in Bienville’s eye yet; the only settlements in the entire colony were tiny outposts at Ship Island, Fort Maurepas, and Massacre Island (Dauphin Island). In 1702 Iberville had established Mobile, called Fort Louis de la Mobile or Fort Louis de la Louisiane, with the intention of growing it into a large, thriving colonial capital. It was little more than a camp, located at present-day Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff and populated mostly by Canadian fur trappers and French soldiers. (The site of Fort Louis, now referred to as Old Mobile, completely flooded and was abandoned in 1711 for Mobile’s present-day location.) Not even a real parish church existed yet; in the same letter about the Pélican, Pontchartrain told Bienville he was sending 600 livres to replace or enhance the makeshift structure that had been hastily erected to consecrate the newly created diocese.

God, king, and family were bound together in the logic of New France, with women and children serving a vital role. The Catholic Church was central to France’s imperial designs: it was the moral scaffolding by which the French claimed and inhabited a land entirely unknown to them, enslaving many of the indigenous sauvages so as to save their souls while extracting their labor. Devotion to the Holy Family was especially prevalent in Canada; a confraternity (Catholic devotional group) dedicated to the Sainte-Famille had been established by the Bishop of Quebec in the late 1660s, and it was popularized over the following decades by the wife of the governor. As bearers of both children and French religion and custom in the home, French women held practical and cultural importance to the Louisiana colony. “The more respectable [families] there are here, the more we shall live in peace and harmony,” wrote ordonnateur (fiscal officer) Bernard Diron d’Artaguiette.

This 1710 painting (left) by Alexis Grimou shows a robust-looking Bernard Diron d’Artaguiette. Chief financial officer of the colony, d’Artaguiette supported Bienville’s move to cut Marie Grissot’s salary. As minister of the French navy during Louisiana’s early years, Jérôme Phélypeaux, comte de Pontchartrain (right), oversaw the affairs of the colony and fielded many complaints from its residents and officers, including Grissot and Bienville. (left: courtesy of Wikicommons; right: THNOC, 78-429-RL)

In Mobile, the resident Canadians, hard-living coureurs de bois, were seen as “a heap of the dregs of Canada, jailbirds without subordination for religion and for government,” as Antoine Laumet de La Mothe Cadillac, governor of Louisiana from 1710 to 1716, later described them. Many of the Canadians lived with Native American women; some of these relationships were explicitly forced, through enslavement, while others assumed a more nebulous form, yet the higher-up officials viewed all such arrangements as “shameless dissoluteness,” as Pontchartrain described the situation in 1711. “It is quite contrary to religion and to the increase of the colony.”

The young female conscripts of the Pélican were seen as crucial to reversing that trend and to helping both the Canadians and Native Americans adopt European custom. “This will make them very useful to the colony by showing the daughters of the Indians what they can do,” Pontchartrain wrote.

But these new arrivals would need help. “By the same vessel, his Majesty is sending a midwife,” Pontchartrain told Bienville. The midwife in question, however, was not Marie Grissot. It was Catherine Moulois, a master midwife who had trained in Paris. Under the king’s employ, she was granted an annual salary of 400 livres. In comparison, Bienville’s salary was 1,200 livres per year. Grissot, a native of Lorraine, and another unmarried woman, the widow Marie Linant, were hired to look after the health and safety of the girls and assist Moulois as needed.

The Pélican completed its three-month transatlantic voyage in July 1704, and “a short time after arriving all the girls married the Canadians and others [French craftsmen and soldiers] who are in a position to support them,” Bienville reported to Pontchartrain.

Bringing Life into a World of Hardship

Not long after the Pélican’s arrival, Catherine Moulois died or disappeared—her death is not confirmed in the historical record—and Grissot took over as midwife of the colony, inheriting the job’s 400 livres-per-year salary. As early as October 1704, Grissot is documented as having helped deliver a child into the colony. The first census conducted after the arrival of the Pélican, from 1706, lists her as midwife.

As sage-femme, Grissot and others that followed her held a level of authority and independence uncommon for most women of the time. In addition to earning a sizeable royal salary, she was able to “enter any home, and could travel at all hours throughout the colony,” according to K. Hanley, who curated Midwifery and Obstetrics in Louisiana, a 2017–18 exhibition mounted by the New Orleans Pharmacy Museum. In addition to receiving a salary, Grissot held enslaved people in her service: in 1708 she presented for baptism a man named André, listed as belonging to her, and one census documents four enslaved Native Americans (three male and one female) belonging to the midwives.

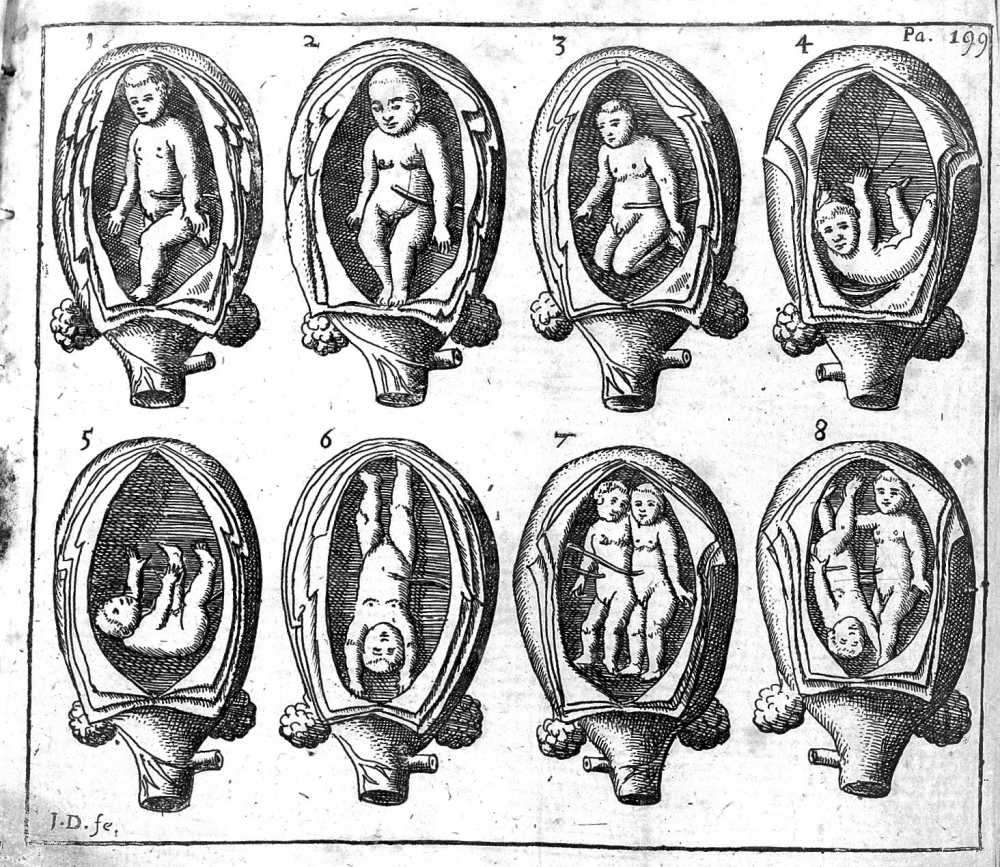

The Scientific Revolution and the advent of the printing press brought about the codification of medical knowledge such as midwifery over the course of the late 16th and 17th centuries. The English midwife Jane Sharp first published The Midwives Book in 1670; it went through many other editions (the frontispiece to the 1724 edition, known as The Compleat Midwife's Companion, is seen here) and would have been in use at the time of Louisiana's founding.

Grissot held religious authority, as well: she was able to perform home baptisms in cases where the newborn was not expected to live. Baptismal records of the Archdiocese of Mobile show Grissot carrying out this sad service a number of times. On October 22, 1704, Grissot baptized a boy born to François and Anne Le May—the second child of European settlers to be born in the entire colony. (The first, it appears, arrived two weeks prior: Jean-François Le Camp was born October 4, 1704, and the 1706 census describes him as the “first child born in the colony,” leaving aside the obvious primacy of Native Americans.) The Le May child, however, was not to join the first generation of Louisiana Creoles: the baby died and was buried the same day it was born.

The following winter, of 1705, was especially fatal for the infants of the colony. Accounts differ, but it’s estimated that at least three newborns died. Accusations flew about who was to blame—Bienville accused the parish curé, Henri Roulleaux de La Vente, of baptizing the children naked in winter, and one family complained that Bienville did not allow them a ration of milk during the infant’s illness—but the record does not show Grissot’s level of care being called into question. At the time, even in the palaces of Europe, childbirth presented life-threatening risk to mothers and babies; no one in the colony would have been unfamiliar with the reality of infant mortality.

The miserable conditions in Louisiana made survival difficult for everyone, young and old. “There is nothing so sad as the situation of this poor colony,” began one report in 1708. Yellow fever had already torn through the settlement in 1704, arriving with the Pélican from the ship’s stop in Havana and killing approximately 40 people. A tropical storm (“violent squall”) blew down Mobile’s warehouse and several other structures in August 1708. Livestock was scarce, and supply ships often suffered long delays.

The colonists’ attempts to grow wheat and corn as subsistence crops failed utterly: none of them were skilled agricultural workers, and few were desirous of becoming so. Sandy soil and flooding killed many of the plants, and what little grain survived to harvest was quickly spoiled by pests. The agricultural tribes around Mobile successfully grew corn and traded maize with the colonists, but excessive flooding killed some of their crops in 1710—when the colony had not seen a French supply ship since 1708.

More than once, conditions were so dire and famine so imminent that Bienville sent groups of soldiers to live with allied tribes for the winter, because the colony could not provide for them.

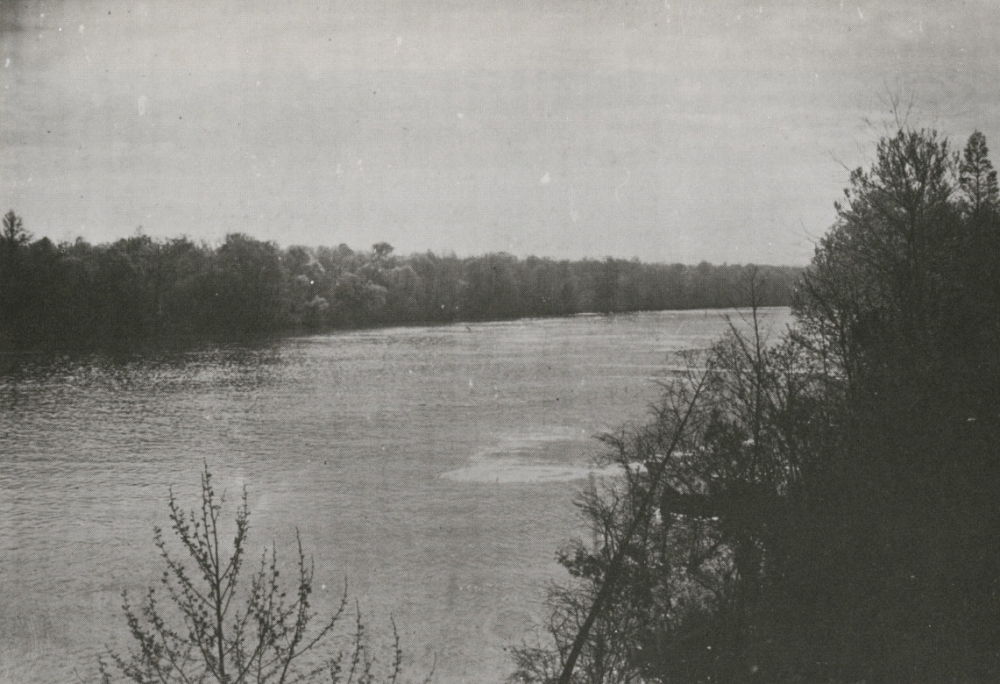

This 1974 image, from Jay Higginbotham’s Old Mobile: Fort Louis de la Louisiane, 1702–1711 (1977), shows the site of Old Mobile facing downriver. The town was originally situated on Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff, 23 miles north of where Mobile sits today. Excessive flooding in 1711 destroyed the settlement and prompted Bienville to move the capital downriver. (Image by John Martin Freeman; THNOC, 78-429-RL)

Bienville’s Gambit and the Feud with Grissot

Bienville’s plans for Louisiana were failing, as was his health. Over 1707 and 1708 he lobbied, unsuccessfully, to make a return trip to France, believing that it would cure his “sciatic rheumatism . . . hepatatic colic and gout.” In short, he was desperate, and it was around this time that he attempted to relieve Marie Grissot of her salary.

Grissot immediately shot back, complaining to Pontchartrain through Nicolas de La Salle, who related the midwife’s testimony in a 1709 letter to Versailles. La Salle, the colony’s commissaire (supply chief), was a veteran bureaucrat 30 years Bienville’s senior, and he had recently launched a raft of mismanagement allegations against the young leader, dividing the loyalties of the colonists. Grissot said she had refused to back Bienville and that ever since, he had “authorized whatever evil he wished upon her, by making the argument that a midwife is useless in this Colony, where, he says, the women can give birth on their own.”

Grissot pointed to several “accidents” that had happened prior to her and Moulois’s arrival as evidence to the contrary. “She hopes that in consideration of her zeal and her dedication to her duties, and because she left her country to come to this Colony, orders shall be given to maintain her in her employment against the persecution of Sieur de Bienville.”

Fetuses in the womb as illustrated in the first edition of Jane Sharp's midwifery manual, The Midwives Book; or, the Whole Art of Midwifery Discovered (1670). None of the babies shown here are in an ideal presentation (position) for birth, which highlights some of the many dangers Grissot’s patients faced in bearing children.

Bienville’s justification was that Grissot was neglecting her duties: he claimed she was supposed to be tending to the sick of the entire population, as well as laundering the soldiers’ linens. “Mr. d’Artaguiette and I thought that it was useless to have a salary given to a person for no service at all,” he wrote. Grissot said there had been no such scope of work over the preceding years of her service, and moreover, mixing with potentially infectious patients amounted to medical malpractice: in a letter of support from Governor Cadillac to Pontchartrain, she argued that “the care of the sick was contrary to her profession; that the majority of the soldiers were subject to scurvy”—mistakenly believed to be contagious—“and that thus after having cared for the scurvy patients she could not at all touch the women in childbed or even the children at birth without running the risk of communicating the disease to them.”

The slashing of royal salaries was not uncommon during these years, both in Louisiana and France. Draining money on war with the English and financing other colonial operations abroad, the mother country was running up debts. Many of the soldiers at Mobile who were promised pay never received more than their basic rations. However, though the circumstances may have warranted a cut, Bienville broke rank by doing so summarily, and Pontchartrain was animated by Bienville’s presumption.

The ministère sent a succinct rebuke to Bienville: “I have been informed that you have treated badly the woman named Marie Grisot [sic], a midwife, and that you attempted to prevent her from performing the duties for which she was appointed. . . . I must tell you that since this woman was sent there by the King’s order, His Majesty’s intention is that she should remain there, that she should serve there, and that you should be careful not to give her any bad treatment.”

In 1711, after receiving Pontchartrain’s orders, Bienville and d’Artaguiette presented what they considered a compromise: reinstating Grissot’s salary at 50 percent, taking it from 400 to 200 livres. The other 200 livres they gave to Pénigault, the carpenter, “who is much more useful,” they argued.

For Pénigault (alternately spelled Pénicaut, Pénigaut, and Perricault), it helped that he was cut from the same cloth as Bienville. He had worked as a shipbuilder and accompanied Iberville in 1699 on the captain’s first exploration of the Mississippi Valley, during which time he began keeping a journal. Like Bienville, he traveled extensively and sojourned with the Natchez, Acolapissa, and Natchitoches peoples, learning some of their languages and customs. After he returned to France in 1721, he compiled his journals and recollections into a narrative, the first full-length account of the French in Louisiana. Neither Grissot nor her services are mentioned anywhere in the document. Just as she excised him from her will, Pénigault omitted her from his story, which was published in English in 1953 as Fleur de Lys and Calumet: Being the Pénicaut Narrative of French Adventure in Louisiana.

The Louisiana Grissot Left Behind

The exact date of Grissot’s death is not known, but presumably it occurred not long after she made her will that Christmas of 1718. Her name disappears from the Mobile baptismal register after June 1717. At the time Grissot died, Louisiana was in a period of transition: in August 1717 France handed control of the colony to the Company of the West, the brainchild of Scottish gambler and financier John Law. In less than three years’ time it would cause a massive financial boom and bust.

Historian Jay Higginbotham referenced colonial sketches to re-create the layout of Fort Louis, the main military and administrative structure of Old Mobile. This map shows the quarters of both Bienville and Nicolas de La Salle, the commissaire (supply chief) and Bienville’s eventual rival. (THNOC, 78-429-RL)

Bienville turned his attention elsewhere, to a new site for the colonial capital 140 miles to the west. By June 1718, months before Grissot died, Bienville’s team was clearing land for what would become New Orleans. Three years later, Grissot’s first official successor arrived: Jeanne Sulmon Dauvillé, a master midwife from Paris, was sent to New Orleans under an annual salary of 1,200 livres—a far cry from Grissot’s pay even at its fullest. She would remain the colony’s only official midwife until 1749.

Grissot and the women and children she served endured unimaginable hardship and loss, facing steep odds to fulfill the reproductive roles France had assigned them. Despite the greater failure of Mobile as a colonial capital and economic engine, Grissot and her patients played an essential role in populating the young colony. Each successful birth must have infused the downtrodden settlement with a dose of the mirth and hope that only new life can bring.

Commissaire Nicolas de La Salle had lost his first wife and youngest son within two years of arriving in Louisiana, but on March 22, 1708, he and his new Pélican bride, Jeanne-Catherine de Berenhardt, welcomed a baby boy, christened Henri. He was 53; she was between 18 and 22 and had been specially selected for La Salle by a duchess in Paris, sealing her fate. The child would be orphaned two years later, and La Salle’s five-year-old son from his first wife died as well, but for a short while, they were a family.

Such was the dream and folly of colonial imperialism: filling distant shores not only with French forts, plantations, and statesmen but also French families, so that the glory of France could spread around the world.

Special thanks to THNOC Curator Howard Margot for his generous assistance and expertise with the French archival documents referenced in this story.