In November 1941, a few days before the United States entered World War II in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Tennessee Williams was already thinking about the impending global conflagration’s impact on his art.

“I think there is going to be a vast hunger for life after all this death—and for light after all this eclipse,” he wrote to fellow playwright William Saroyan, in a letter displayed in the exhibition Backstage at “A Streetcar Named Desire,” on view at The Historic New Orleans Collection through July 3, 2022. “People will want to read, see, feel the living truth and they will revolt against the sing-song Mother Goose book of lies that are being fed to them.”

When Williams’s New Orleans–set A Streetcar Named Desire opened on Broadway in December 1947, the living truth of the war’s effect on returning service members was embodied in the drama’s antagonist—the aggressive, cynical, explosively violent Stanley Kowalski, who crushes his fragile, unstable sister-in-law, Blanche DuBois.

Williams was spare with his creation’s World War II service history but salted the Streetcar script with just enough specific detail to provide audiences a window into Stanley’s war and how it might’ve shaped him. They learned that Stanley was a decorated master sergeant in an engineer combat unit and that he saw action at the Mediterranean port city of Salerno, Italy, about 40 miles southeast of Naples and 170 miles from Rome. Combat engineers were a vital cog in the Allied war machine in this theater, given Italy’s beaches, mountains, rivers, and minefields. (The script’s reference to the 241st unit in which Stanley and his friend Harold “Mitch” Mitchell served was the playwright’s theatrical license; the engineer combat regiment at Salerno was the 540th.)

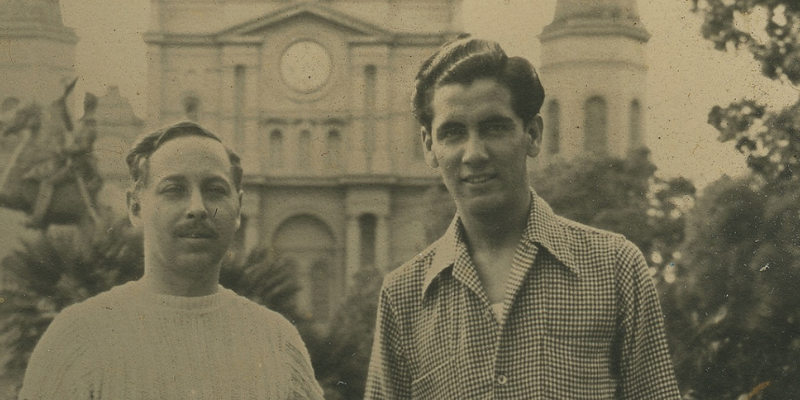

Tennessee Williams (left) with his partner Pancho Rodriguez y Gonzalez (right) in Jackson Square, ca. 1945. (The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2003.0228.1.1)

A Sympathetic Villain

Scholars have explored the postwar surge of returning-veteran characters on stage and screen, placing Stanley Kowalski in comparative context. Writing in the Tennessee Williams Annual Review in 2009, Larry Blades concludes that the 1951 film of Streetcar was “a much bleaker, less ‘Hollywood’ view of the reintegration of the returning vet” than was seen in The Best Years of Our Lives and Till the End of Time, two acclaimed 1946 films that spotlight the subject. In a 2019 master’s thesis, Charles McCaffrey compares veteran portrayals in Arthur Miller’s All My Sons, Sidney Kingsley’s Detective Story, and Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, noting that Williams, drawing from life, based Stanley in part on his lover Pancho Rodriguez y Gonzalez, a World War II veteran of the Pacific theater who abused both alcohol and Williams and described himself as “a casualty of war.”

Williams’s aim, McCaffrey said in an interview, was to use audience knowledge of Stanley’s service experience to create a “sympathetic villain” in, as Williams himself wrote, “a tragedy of misunderstanding and insensitivity to others.”

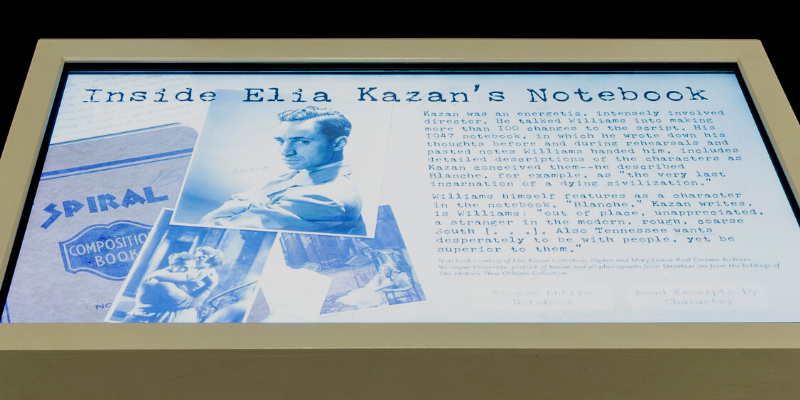

Elia Kazan, who directed both the 1947 stage and 1951 screen versions of Streetcar, kept a production journal, a digital facsimile of which can be browsed in the Backstage exhibition. In it, Kazan conducted a running analysis of each of the work’s main characters. Stanley, he wrote, is “deeply dissatisfied, deeply hopeless, deeply cynical” and dealing with his postwar frustrations by pursuing consumption—of food, alcohol, sex. “He’s desperately trying to squeeze out happiness,” Kazan observed. “And it really doesn’t work… Bec. it simply stores up violence and stores up violence, until every BAR IN THE NATION IS FULL OF STANLEYS READY TO EXPLODE.”

Director Elia Kazan’s production notebook is on display in the exhibition Backstage at “A Streetcar Named Desire.” (THNOC)

Salerno

What did Stanley Kowalski do in the war? Where in Williams’s character are the effects of service visible?

At Salerno, an amphibious Allied invasion on September 9, 1943, resulted in near disaster. Operation Avalanche commenced without naval or aerial bombardment support, supposedly to preserve tactical surprise (it didn’t), and resulted in several days of lethal volleys of Allied attack and Axis counterattack.

“The British-American operation that started September 9 encountered ferocious German resistance,” said Jason Dawsey, a research historian at the National WWII Museum’s Institute for the Study of War and Democracy. “It was really a weeklong operation getting the Salerno beachhead secured.”

An Associated Press dispatch that ran at the top of the front page of the September 17, 1943, edition of the Times-Picayune finally reported the invading force’s breakout from the German “siege ring” that had stymied the operation. The Allies “regained ground lost to the five fanatical Nazi divisions which for a sleepless week had tried vainly to push the Allies into the sea,” the story reported.

The Allied Italian campaign pushed onward through the June 1944 liberation of Rome and beyond, against an enemy expert in fighting from superior defensive positions. The terrain taken from the Germans during the grueling advance was mountainous and laced with rivers, geography that combat engineers would be charged with navigating.

“Engineer combat units are best remembered, yes, for bridge building,” Dawsey said. “They do other things that shouldn’t be forgotten, too: building beachheads in amphibious operations, clearing obstacles that the enemy had put up, roadwork, airstrips, clearing mines. They had a wide array of tasks and oftentimes they were doing this under enemy fire.”

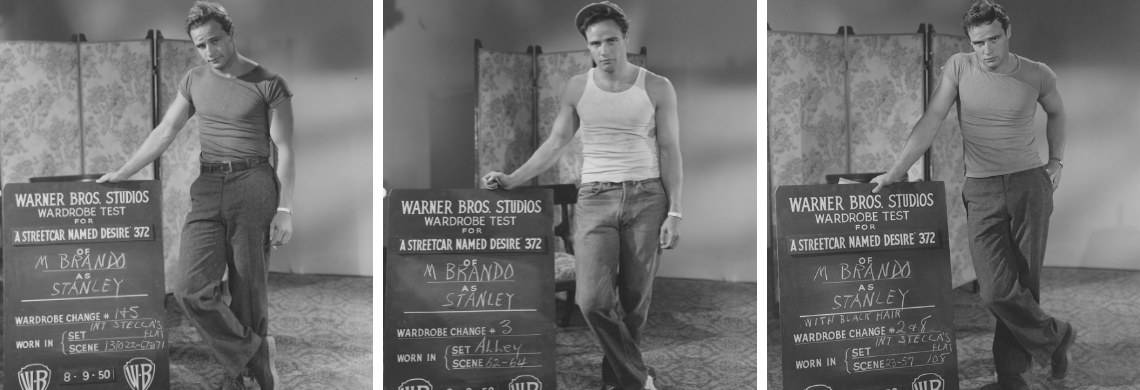

Marlon Brando as Stanley Kowalski in the 1951 film version of A Streetcar Named Desire. (The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2001-10-L.1247)

Invisible Wounds

“I was at the foot of the mule trail the night they brought Capt. Waskow’s body down,” wrote syndicated war correspondent Ernie Pyle in a dispatch datelined “At the Front Lines in Italy, January 10, 1944.” “Dead men had been coming down the mountain all evening, lashed onto the backs of mules. They came lying belly-down across the wooden pack-saddles, their heads hanging down on the left side of the mule, their stiffened legs sticking out awkwardly from the other side, bobbing up and down as the mule walked.”

In addition to consuming years of harrowing frontline war correspondence, the first American theatergoers to meet Stanley Kowalski had also been served lots of journalistic concern about the effect on returning veterans’ psyches caused by scenes like the one Pyle described. McCaffrey’s thesis surveys popular wartime print media and finds numerous speculative stories anticipating “psychoneurotic casualties” among returning veterans.

“Near the end of the war and through the early postwar period almost every print article that discussed veterans included a side story of at least one combat veteran with mental health issues,” writes McCaffrey, an instructor of English and history at North Central Michigan College (and an Army infantry combat veteran of the war in Afghanistan).

So, “there’s a curiosity that’s going on in the audience,” McCaffrey said in an interview. “And an awareness that some of these men have come back and have . . . invisible wounds.”

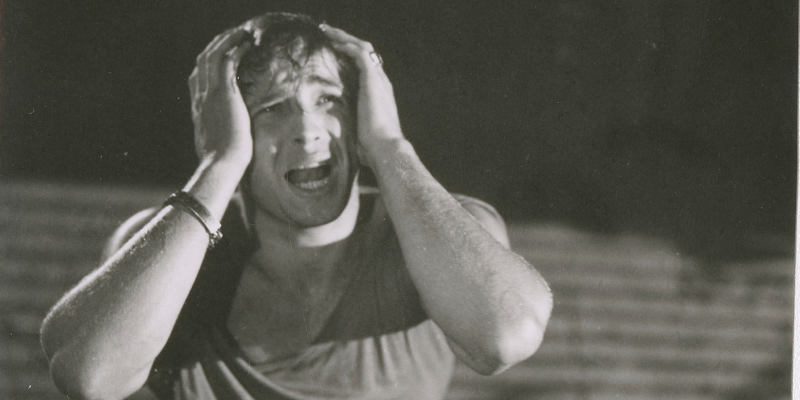

An image from a lobby card for the 1951 film of A Streetcar Named Desire. (The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2001-10-L.2267)

Battle Neurosis, the PTSD of Its Day

Audiences in the 1940s and ’50s might have recognized Stanley’s hypersensitivity to insult or threat and his violent overreactions (as well as Blanche’s loose grip on reality) as symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), though that medical diagnosis wouldn’t be adopted for decades.

During and after World War II, the condition “was referred to as battle neurosis more often than not,” said Stephanie Hinnershitz, historian for the National WWII Museum’s Institute for the Study of War and Democracy. “It wasn’t treated the way we would treat or approach PTSD today.”

For World War II veterans, there was no long-term treatment for battle neurosis, Hinnershitz said, adding, “It was something people thought would eventually go away on its own as service members reintegrated back into normal life.

“Of course, that’s not what happened.”

Symptoms of battle neurosis mirror a Stanley Kowalski personality profile: fear, anxiety, alcoholism, more. “Behavior like Stanley’s, his impulsive behavior, his outbursts—that would have been very recognizable to most people,” Hinnershitz said.

Due to the popular press’s coverage of “psychoneurotic casualties,” the symptoms would be familiar to Streetcar audience members even if they hadn’t had direct personal contact with a combat veteran (such contact was a statistical improbability anyway, McCaffrey observes, given that only about 6 percent of Americans who served in World War II experienced frontline combat).

Near the end of the war, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, addressed public concern about the mental challenges facing returning soldiers. “For God’s sakes don’t psychoanalyze them,” he said in a 1945 press conference, as cited by McCaffrey. “They are perfectly normal human beings. They have been through a lot and very naturally they want a pat on the back and they want to be told they are pretty good fellows and they are. But they want to be treated just like they were treated when they went away.”

In creating Stanley—a soldier who risked his life for a country that still looks down on his ethnicity and working-class background, but also a rapist who lies and banishes his sister-in-law to a mental institution—Williams skewers this reductive portrait of traumatized veterans. No one can call Stanley a “pretty good” fellow who has “been through a lot” and just wants “a pat on the back” and to be treated as though he is the same person he was before he went to war.

Marlon Brando and Kim Hunter on the set of the film production of A Streetcar Named Desire, 1951; (The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2001-10-L.1246)

“Luck Is Believing You’re Lucky”

Fighting in Italy would continue for a year after the Allies liberated Rome.

“The Italian campaign after Rome turns into a brutal and prolonged battle of attrition on the Italian peninsula as the Allies push up the boot,” Dawsey said. Though the fighting continued, home-front interest turned elsewhere in the European theater. Just days after the liberation of Rome, the Allied D-Day invasion of Normandy largely pushed news from Italy off of front pages back home.

“The Italian theater was largely overshadowed by the Allied war effort in France,” Dawsey said. “The western front had a huge effect on the way Americans remember the Italian campaign.”

The race to Berlin from the Normandy beaches instantly became better copy than the push up the boot, as brutal and prolonged as it was. World War II veterans of the Italian campaign visiting the National WWII Museum have expressed to staffers there that they sometimes fear they’ve been forgotten.

From the invasion of Sicily in July 1943 to Germany’s surrender in Italy in April 1945, estimated Allied and Axis casualties approached 700,000, with more than 60,000 Allied combat deaths.

“You know what luck is?” Stanley imparts to his poker buddies in Streetcar’s final scene, a poker party interrupted by the doctor and nurse whom Stanley has summoned to take Blanche away. “Luck is believing you’re lucky. Take at Salerno. I believed I was lucky. I figured that 4 out of 5 would not come through but I would . . . and I did. I put that down as a rule. To hold front position in this rat-race you’ve got to believe you are lucky.”