New Orleans history goes back beyond the founding of the city over 300 years ago and contains a whole world of subjects, movements, people, and periods, encompassing colonial history, diasporic history, United States history, arts and culture, technology, war, and so much more. For even longtime lovers and students of the city, it’s a lot to learn. Here at The Historic New Orleans Collection, we never stop looking for stories from our past, and through our publications, programs, and exhibitions—and the First Draft blog—we’ve built a small library’s worth of resources in the form of essays, oral histories, virtual exhibitions, and other online resources. To help introduce readers to New Orleans history writ large, while linking to fuller stories and resources on our website, THNOC’s Visitor Services department compiled this primer—call it New Orleans History 101.

Native Americans

When the French founded the city of New Orleans in 1718, they did so at a site that had been used for centuries by Native Americans as a gathering place for trading, forming alliances, and hunting—today’s French Quarter. The Choctaw named the area “Bulbancha,” meaning Land of Many Tongues, signifying the multi-tribal nature of this location. The land itself was situated on higher ground—information that the French might have learned from Native allies in Mobile—due to middens created by discarded oyster shells and sediment deposits. These conditions, along with convenient access to Lake Pontchartrain through the Bayou St. John portage, made Bulbancha an attractive location for settlement. Despite the devastating effects of European colonization, descendants of the people who once gathered at Bulbancha during the pre-colonial era are still here. The Jena Band of Choctaw, Tunica-Biloxi, Coushatta, and Chitimacha are all federally recognized tribes. Although state-recognized since 1977, the Houma still struggle to achieve federal designation.

A Native American woman sells bundles of botanicals at the French Market in 1891. (THNOC, gift of Mary Louise Hammersmith, 1977.79.13)

Colonial Architecture

New Orleans was a planned town, designed by French military engineer Le Blond de la Tour in 1721, and the original grid can be seen in today’s French Quarter. Within a few years, settlers and enslaved Africans constructed permanent housing using native cypress. Elevated off the ground, the earliest French colonial houses had pitched roofs, few windows, and no porches. The houses were spaced out, with gardens in between.

During the Spanish colonial period (1763–1803), two large fires destroyed 1,068 French colonial structures. The Spanish government enacted building codes in 1795 that restricted the use of timber for multi-story buildings, instead favoring bricks and plaster. As the city rebuilt from the fires, houses were constructed close together, often with shared walls and courtyards. These courtyard homes served as an ideal model for future construction in the French Quarter by addressing two basic problems: the need for increasing density due to a growing population and the sometimes uncomfortable subtropical climate.

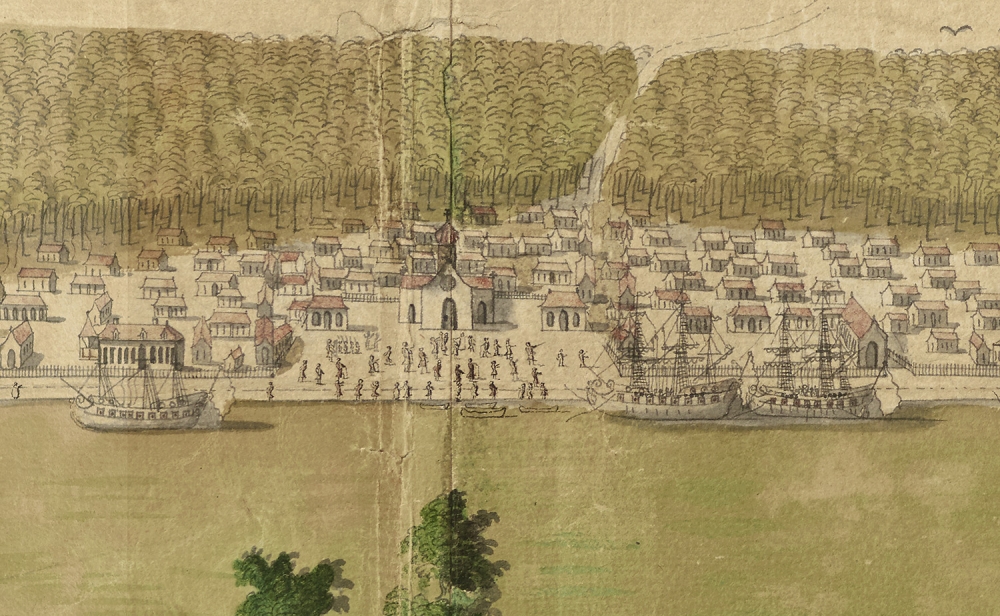

This detail of a 1726 watercolor shows the pitched roofs and spaced-out structures of the French colonial period. (Courtesy of the Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer; black-and-white copy via THNOC, 1974.25.8.3)

Slavery

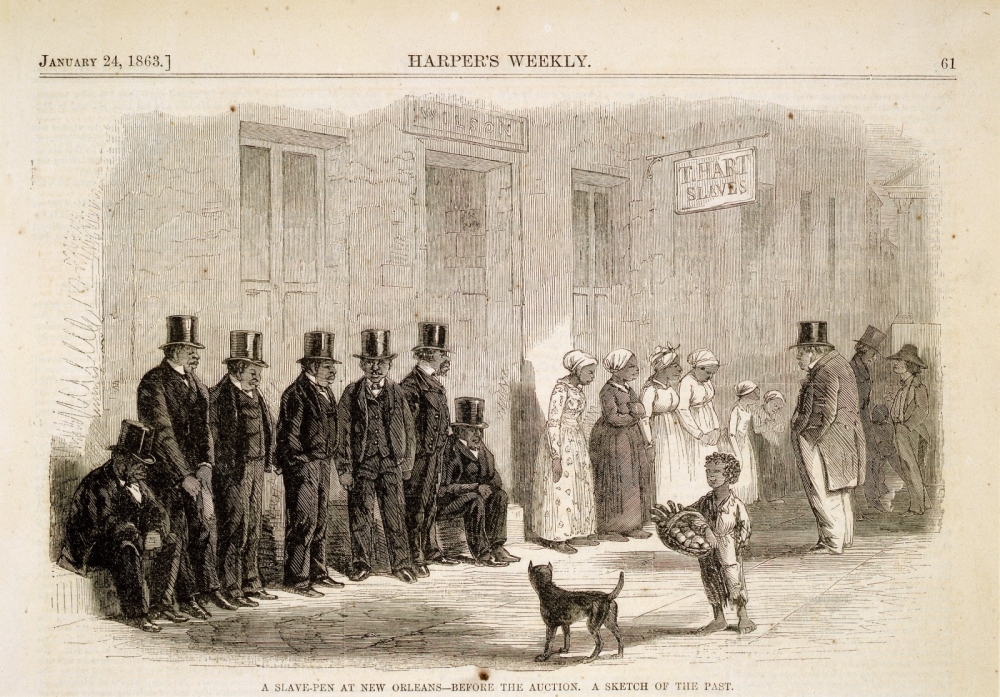

New Orleans was built on the enslavement of Africans and their descendants. Enslaved men, women, and children constructed the city’s infrastructure, provided domestic labor, sold goods in the markets, and built many of the houses and buildings still seen today. Their cultural and spiritual traditions, skills, and knowledge fundamentally shaped all aspects of the city. The first enslaved Africans were brought to the city in 1719, a year after its founding. Around 6,000 people were forcibly removed from the West African coast, many from Senegambia, and brought to Louisiana during the French period. The Spanish imported a similarly sized group from the Benin and Congo regions in the 1780s. When New Orleans became an American city in 1803, enslaved Africans and their descendants made up over one-third of the population. By 1820, New Orleans was the center of the domestic slave trade, which forcibly moved over one million enslaved people from the Upper South to the Deep South by 1860.

Though the international slave trade was outlawed in 1808, sales of enslaved people within the United States was still legal, and New Orleans was the center of the trade. (THNOC, 1958.43.24)

Free People of Color

Free people of African descent appear in New Orleans records as early as 1722, just a few years after Bienville founded the city in 1718. During the French period, militia service and individual acts of manumission offered avenues to freedom, while the surrounding swamps sheltered enslaved residents who ran away. Under the Spanish, the population of free people of color expanded considerably. The Spanish law of coartación, or self-purchase, allowed enslaved individuals to buy their freedom. Voluntary manumission—especially of women and children—by enslavers also increased. Following the resettlement of over 3,000 free people of color from Haiti in the early American period, the population tripled. Over time, free people of color formed communities built on multigenerational freedom with strong ties to family and place. By 1860, New Orleans had the largest free Black population in the Deep South. Most free people of color were French-speaking, and many owned property. Free men and women of color were skilled artisans, entrepreneurs, teachers, poets, and activists during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

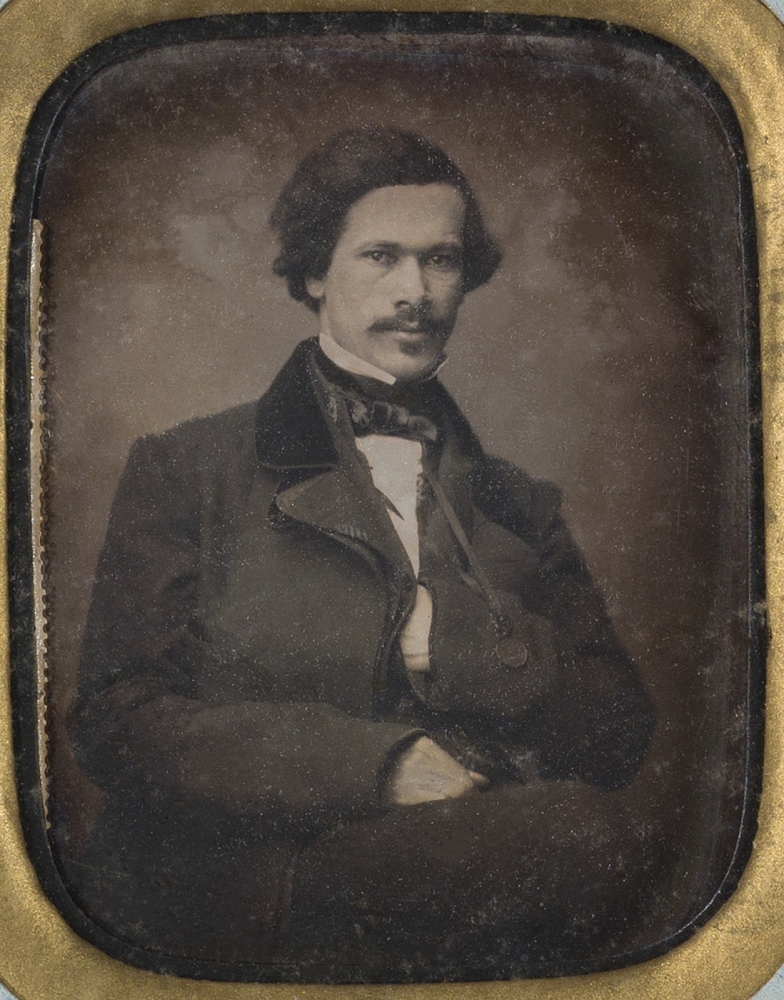

Dr. Louis-Charles Roudanez was a prominent New Orleanian who founded two bilingual Black newspapers, L’Union and La Tribune de La Nouvelle Orleans, in the 1860s. These papers helped foster early civil rights movements in New Orleans. (THNOC, gift of Mark Charles Roudané, 2017.0201.1)

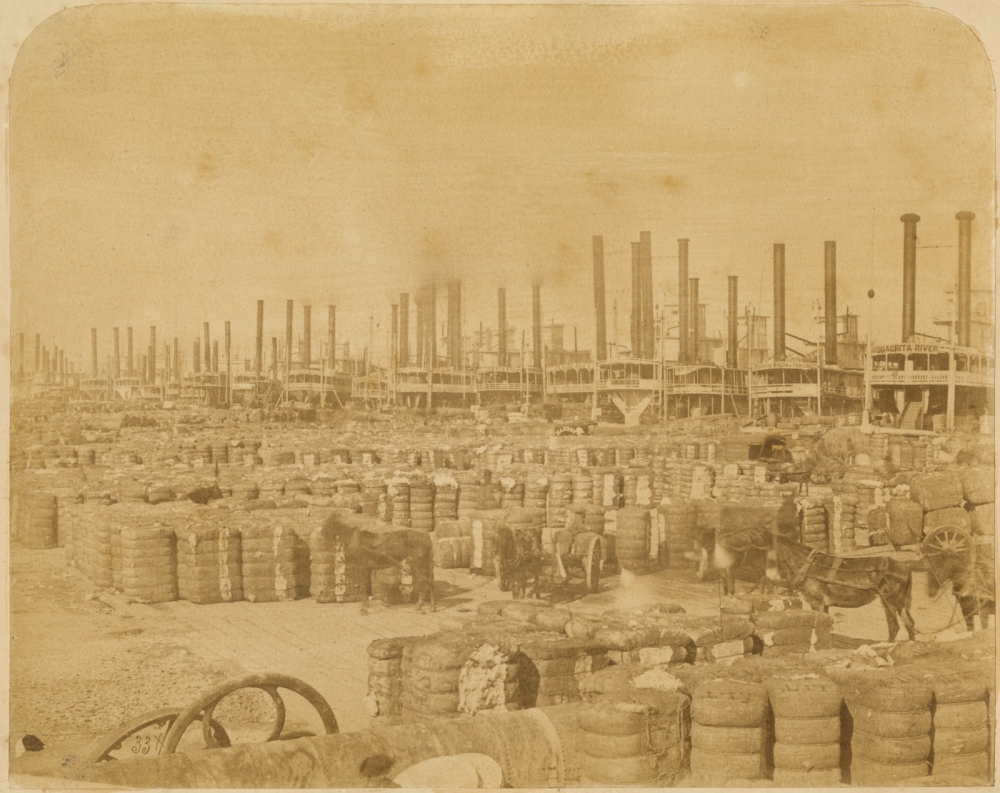

Commerce and the River

After a four-month voyage from Pittsburgh down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, the steamboat New Orleans arrived in its namesake city on January 12, 1812. This event—the first steamboat to navigate the Mississippi—marked a revolution in commerce and travel on the river, allowing for movement both down and upstream. Two-way steam-driven boat traffic on the river led to significant growth and prosperity for the city of New Orleans over the next 50 years.

Approximately 2,350 miles long from its source in Minnesota to where it empties into the Gulf of Mexico, the Mississippi River had been vital to colonial European and, later, American interests since Hernando de Soto set eyes on it in 1541. With the development of steam technology in the early 19th century, New Orleans became one of the largest ports in the world. The city handled trade from the Mississippi River Valley as well as the Eastern seaboard, Europe, the Caribbean, and Latin America.

As seen in this photograph from ca. 1860, the Port of New Orleans was a bustling hub of steamboat traffic. (THNOC, 1985.238)

Immigration

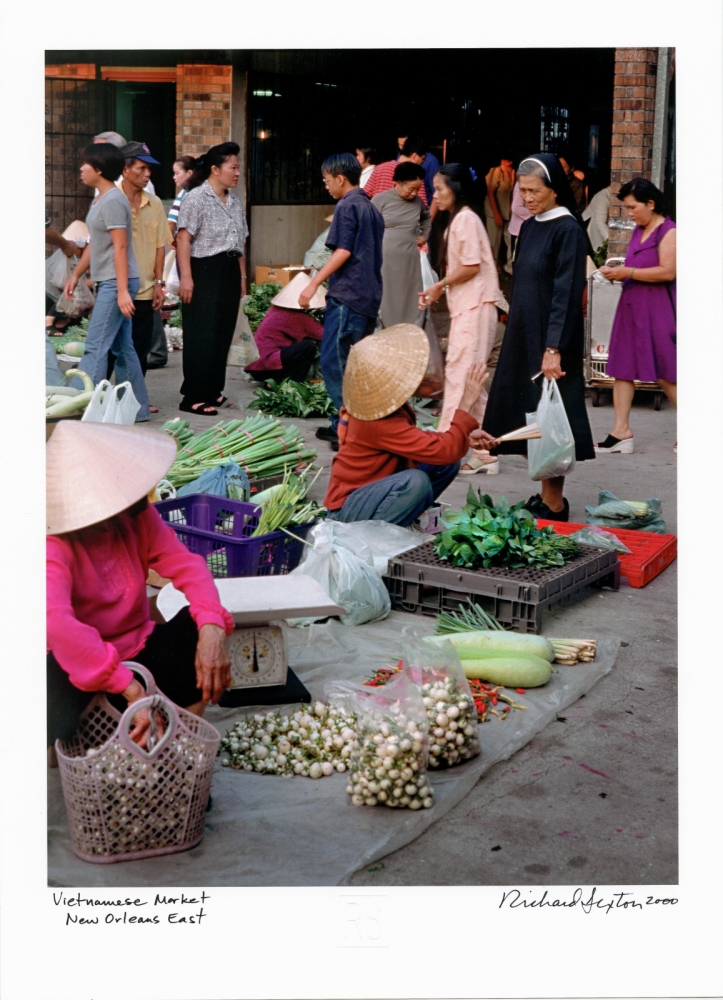

New Orleans is best known for its Creole heritage—a mixture of Native American, French, West African, and Spanish cultures and people. But it is less known as a major point of entry for immigrant groups entering the United States. From 1809 to 1810, over 10,000 Saint-Domingue refugees from the Haitian Revolution settled in New Orleans, doubling its population. Between 1820 and 1860, over half a million people—including Irish, Germans, and Filipinos—landed in New Orleans. Many of these immigrants only passed through the city on their way to settle in other parts of the country. Yet tens of thousands of immigrants stayed. After the Civil War, Italians, Jews, Croatians, Chinese, and others added to the city’s population. More recently, Vietnamese and Latin American immigrants have made new homes in New Orleans. Each generation of immigrants and their descendants has made a lasting impact on the city’s economy and culture.

New Orleans East is home to an active Vietnamese market, as seen here in 2000. (THNOC, 2014.0047.124, © Richard Sexton)

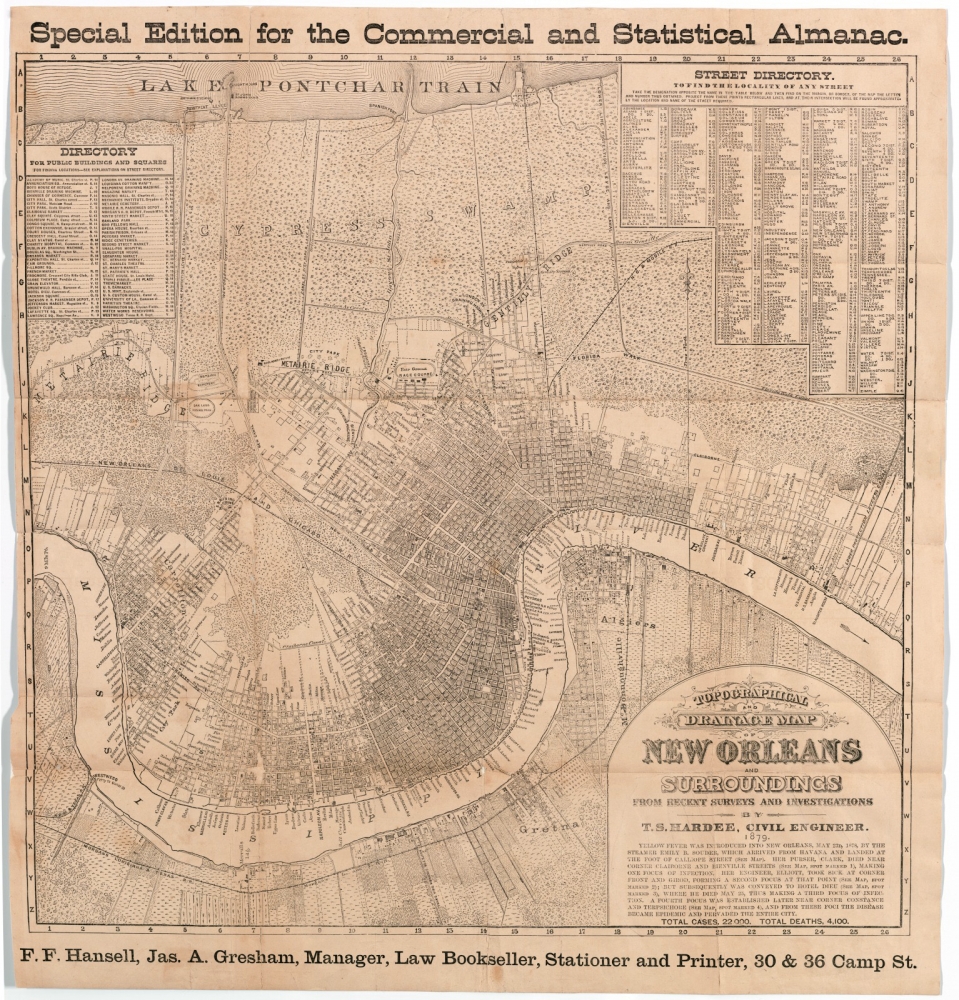

Urban Expansion and Subsidence

Today about half of New Orleans’s geographical area sits below sea level. This sinking occurred over the last three centuries as the city grew beyond the French Quarter and into the surrounding swamps. The sinking process began with early colonists’ efforts to use outflow ditches to move water out of the French Quarter and into the swamps behind the city. A population boom in the early 1800s, along with plantation land sales, motivated city planners to expand beyond the French Quarter, allowing New Orleanians to move upriver into the present-day Central Business District and Uptown and downriver into today’s Marigny and Bywater neighborhoods. Yet it was not until the introduction of pumps in 1915 that the swampy areas toward Lake Pontchartrain could be drained. Draining allowed New Orleanians to develop areas like Broadmoor, Mid City, Gentilly, and the Lakefront, but it also caused the land to sink below sea level.

This 1879 map shows the footprint of New Orleans, before the introduction of pumps allowed the cypress swamps to be drained and developed. (THNOC, 1997.54)

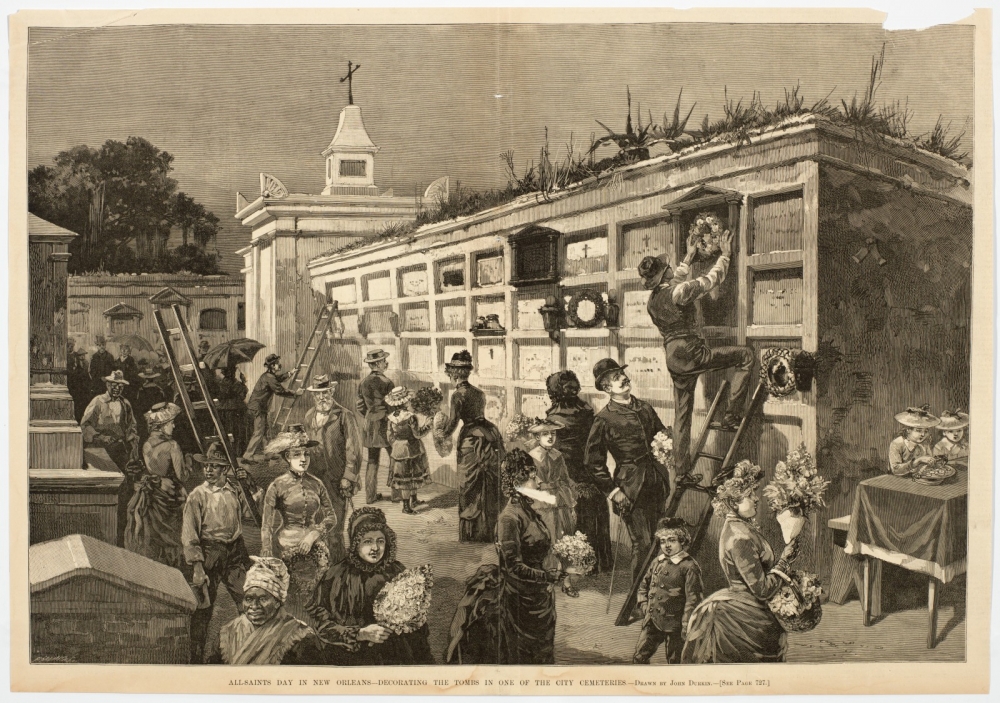

Cemeteries

New Orleans is famous for its cemeteries with their aboveground tombs. It is commonly reported that the tombs are above ground because of the city’s high water table. This, however, is a myth. As the story goes, the entire city is below sea level, and any hole in the ground will fill with water, so anything buried underground will float to the surface. But coffins buried under six feet of soil will not simply float to the surface. New Orleans tombs are aboveground because that is how tombs were built in France and Spain. Cemeteries in Paris also feature multi-vault aboveground tombs, as well as iron crosses and other features common to tombs in New Orleans. In-ground tombs are actually quite common in the city—many built by Protestant and Jewish residents, who prefer this variety.

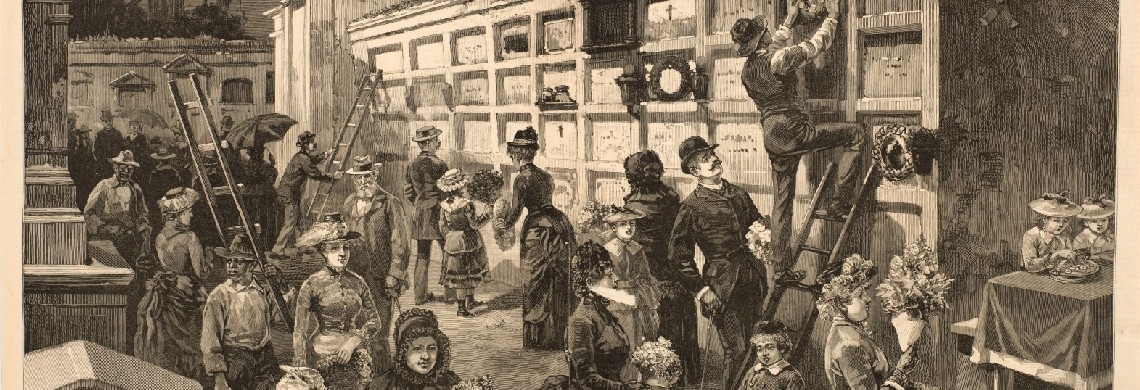

In this 1885 depiction of All Saints’ Day, families decorate a multi-vault aboveground tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1959.204.6)

Po-Boys and the 1929 Streetcar Strike

The poor-boy sandwich, best known as a po-boy, is one of New Orleans’s most iconic foods. The origins of the famous French bread sandwich can be traced back to the 1929 streetcar strike and Martin Brothers restaurant in the French Market. Before opening their restaurant, Benny and Clovis Martin worked as streetcar conductors. When the strike began in July 1929, many businesses publicly supported and encouraged the streetcar workers. Martin Brothers offered the strikers free food. In order to feed so many “poor boys,” the restaurant worked closely with its bread supplier to mass produce a longer and wider loaf of French bread to make its roast beef sandwiches. While the strike lasted four months, the “poor-boy sandwich” continued to be popular. Today the poor-boy is one of New Orleans’s most favorite foods, with many varieties to enjoy—from the iconic roast beef poor-boy to the more recent introduction of Vietnamese poor-boys, or bánh mì.

This streetcar and tool shed were burned in the 1929 streetcar strike. (THNOC, gift of Waldemar S. Nelson, 2003.0182.518)

Civil Rights Movement

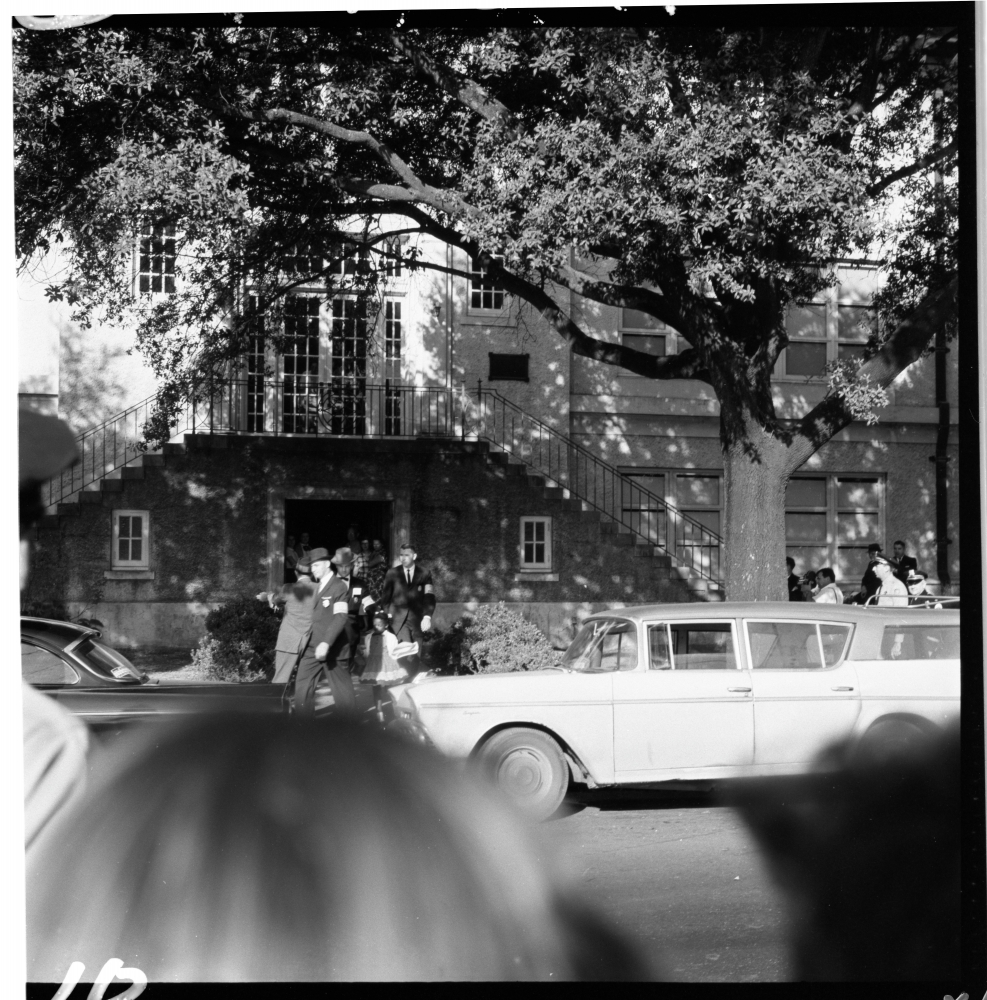

The modern civil rights movement brought about sweeping changes in the city, as Black New Orleanians, following a local tradition of activism that was over a century old, fought for and asserted their rights in education, equal access to businesses and public transportation, and political participation. Local Black youth played a significant role in the movement. In November 1960, four girls—Leona Tate, Gail Etienne, Tessie Prevost, and Ruby Bridges—desegregated New Orleans public schools. They faced harassment and threats to their safety from white New Orleanians. Young men and women in local chapters of CORE and the NAACP Youth Council led efforts to integrate businesses, protest unfair hiring practices, and register Black voters. CORE members risked their lives as Freedom Riders, traveling throughout the South to test compliance with a federal ruling that required integrated interstate travel. Today, organizations like the TEP Center continue to educate people about the history of civil rights in New Orleans, while addressing the ongoing issues of systemic racism.

In November 1960, Leona Tate was escorted into McDonogh 19, desegregating the school. (Jules Cahn Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1996.123.1.107.11)

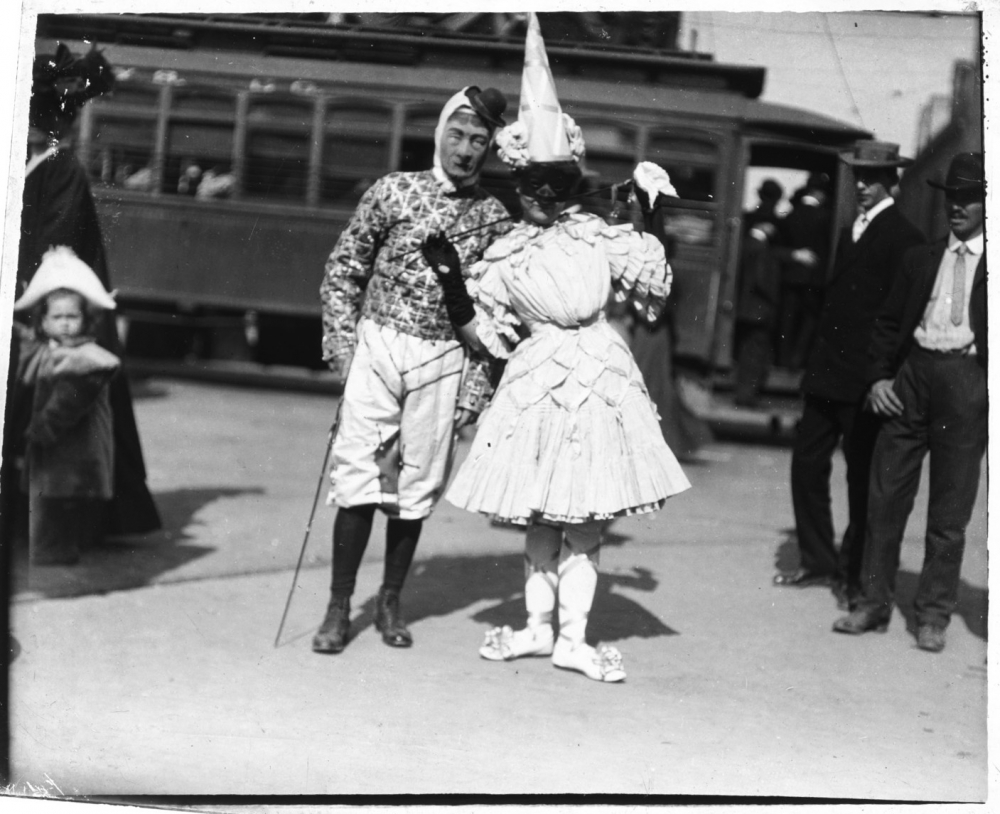

Mardi Gras

Mardi Gras is big business in 21st-century New Orleans, but the celebration of Carnival has a long history in the city. A rare account of Mardi Gras in the French colonial period comes from Marc-Antoine Caillot, a young Parisian clerk only a few months into his employment in the colony. In 1729, Caillot described spending the Sunday before Mardi Gras singing and dancing with friends. Having learned of a wedding reception being held the following night, he proposed forming a party of maskers to attend. Caillot dressed as a shepherdess in a white corset and skirt, complete with beauty marks on his face. Engaging two musicians to join them, 11 costumed and masked partiers arrived at the reception, their way lit by eight enslaved men carrying torches. The revelers danced the night away much to the delight of the hosts. Although much has changed over 300 years, New Orleans carries on the idea that Mardi Gras is a time of role reversal and frivolity open to anyone’s participation.

Since the city’s founding, New Orleanians have created elaborate costumes to celebrate Carnival. These 1907 revelers understood the assignment. (THNOC, 1981.261.54)

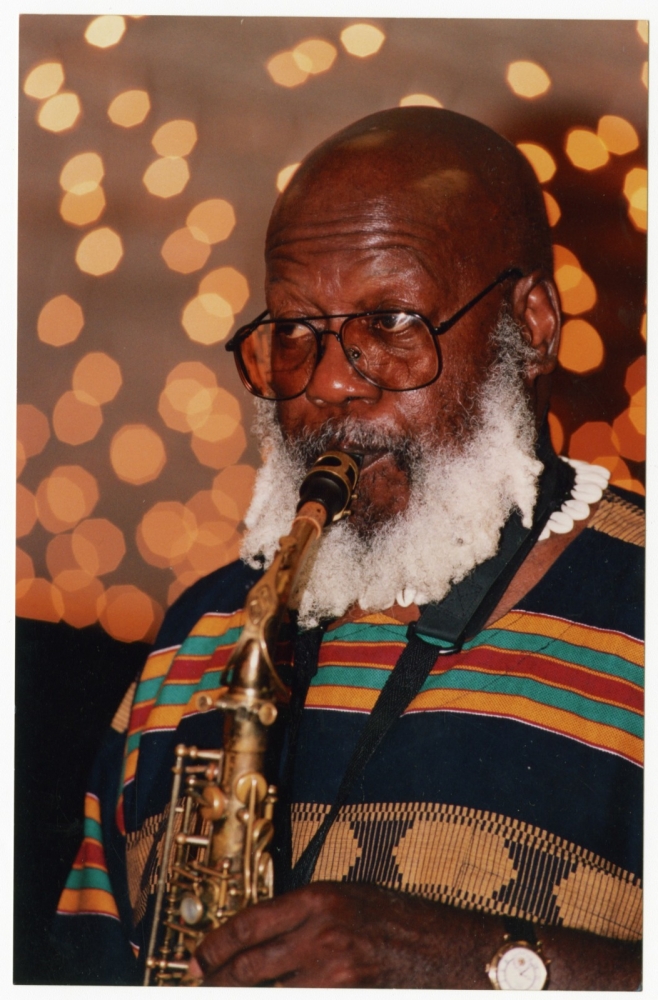

All For One Records

Established on May 29, 1961, AFO (All For One) Records was the first Black-musician-owned record label in the United States. Saxophonist, composer, and producer Harold Battiste and trumpeter and musician union representative Melvin Lastie established AFO for Black musicians in New Orleans to record and collect royalties from their recordings. It also allowed local Black musicians to record without the influence of out-of-town record labels. Battiste gathered a dream team of musicians for the house band, including John Boudreaux (drums), Peter “Chuck” Badie (bass), Allen Toussaint (piano), Roy Montrell (guitar), Alvin “Red” Tyler (saxophone), Melvin Lastie (trumpet), and Battiste on saxophone. They recorded a hit with Barbara George’s “I Know (You Don’t Love Me Anymore)” in 1961. This success got the attention of outside companies, and George’s contract was bought out. In 1963, AFO records went on a hiatus that lasted until the late 1980s or early 1990s. AFO still operates in some capacity today.

Saxophonist Harold Battiste founded the first Black-musician-owned record label in the United States. (THNOC, 2008.0224.4)

Hurricane Katrina

One of the most significant events in recent New Orleans history occurred on August 29, 2005, when Hurricane Katrina made landfall approximately 60 miles south of New Orleans as a Category 3 storm. The subsequent storm surge created three major levee breaches within New Orleans, causing our city to fill up like a bowl. Floodwater submerged 80 percent of the city, and most major roads leading in and out of New Orleans were damaged. The Superdome and Convention Center—shelters for those who did not or could not evacuate—were inadequately equipped. Thousands were stranded on the interstate, hospital patients were evacuated by air, and prisoners were left to fend for themselves. The government’s response to Katrina outraged New Orleans residents and people across the nation. Katrina became the catalyst for a myriad of long-term conversations on flood protection, poverty, evacuation procedures, displacement, systemic racism, cultural erasure, community policing, and historic preservation.

New Orleans Fire Department District Chief Chris Mickal captured this image of the Upper Industrial Canal on September 4, 2005. (THNOC, 2011.0031)

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.