In an 1850 pamphlet summarizing the ongoing litigation of Myra Clark Gaines, journalist Alexander Walker wrote, “The wildest romance ever written, could not contain a greater variety of strange incidents, more affecting details, more strongly marked characters, a more constant succession of stirring events, and stronger exhibitions of folly, intrigue, deception and crime.”

Walker’s report was published less than a third of the way through the marathon case, a 57-year estate battle involving hidden paternity, a destroyed will, and a multimillion-dollar fortune. The case touched all levels of the judicial system and appeared before the United States Supreme Court a total of 17 times. It remains the longest continuous litigation in the history of the country. The legal fight was covered extensively over the decades, granting Gaines a public platform that she used to advocate for women’s rights and suffrage.

Myra Clark Gaines’s fight for the control of her father’s estate lasted 57 years and remains the longest-running court case in US History.

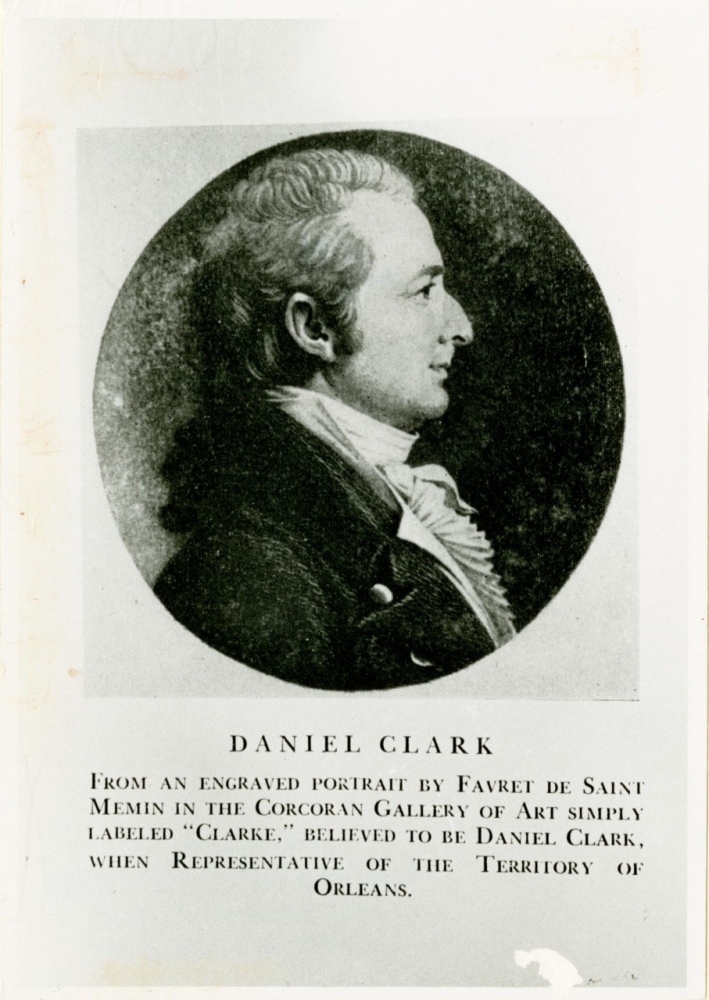

In 1806* Myra Clark Gaines was born to Daniel Clark (inset) and Zulime Carrière. Clark, a wealthy New Orleans businessman and territorial agent, met Carrière, a French Creole socialite, when she was visiting the city around 1802. Their affair, described by one contemporary as “amorous and illicit,” resulted in a secret marriage—secret because Carrière was already married, a relationship she managed to have annulled shortly before Gaines’s birth.

Around the same time, Clark began a relationship with another woman and sought to destroy all documentation of his marriage to Carrière. With Carrière’s blessing, Clark sent the child to live with his close friend Col. Samuel Davis and Davis’s wife, Marian, first in New Orleans and then in Philadelphia. Though he provided financial assistance, Clark did not publicly acknowledge Gaines as his child. Daniel Clark died unexpectedly in 1813, sparking a lengthy fight for his fortune. Deriving from the slave trade, numerous real estate holdings, and countless other spoils from his position in the city’s business elite, Clark’s estate was reportedly worth $35 million—a gargantuan sum at the time.

Gaines grew up believing the Davises to be her parents, and in 1832 she married New York attorney William Wallace Whitney. Around that time (accounts differ as to whether the year was 1830 or 1832), while going through some papers belonging to Col. Davis, she reportedly found a letter from Clark in which he discusses her true parentage. She learned that Clark owned vast swaths of land in New Orleans, including portions of Canal Street and several plantations. A will from 1811 stated that his estate would go to his mother and be administered by two business partners, Beverly Chew and Richard Relf. After Gaines began digging into Clark’s life and business affairs, she found letters referring to another will, made in 1813, that named Gaines as his biological child and declared her the rightful heir to his property and fortune. The will, however, was nowhere to be found.

Gaines learned from several of her father’s friends that Chew and Relf had destroyed the 1813 will. Two of the city’s top power brokers, Chew and Relf controlled most of the banking, shipping, and trading business in New Orleans and had great influence in the courts. Under the guidelines of Clark’s 1811 will, and their management of it, they stood to take the majority of his property and fortune for themselves.

As a woman, Gaines had no legal rights of her own. It was only with the support of her husband that she was able to file her first suit, in 1834. The petition, filed in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, sought to nullify the 1811 will and declare Gaines the rightful inheritor of Clark’s estate.

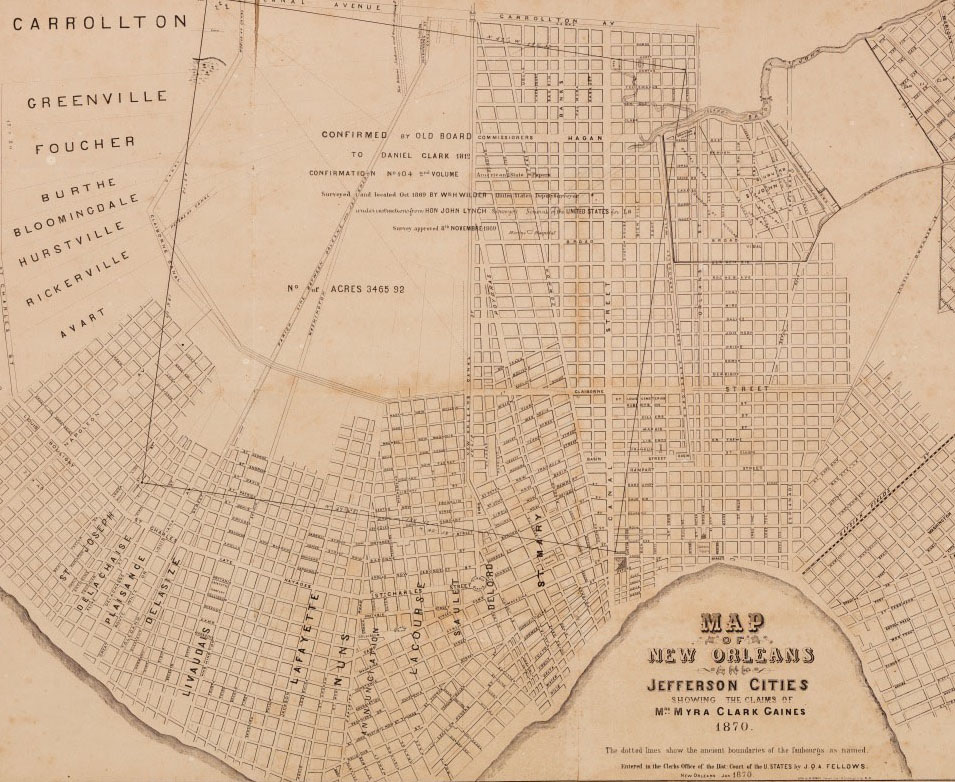

This 1870 map shows the extent of Daniel Clark’s landholdings (marked by the large rectangle), which had been divided and sold by the late 1850s. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1950.17)

This 1870 map shows the extent of Daniel Clark’s landholdings (marked by the large rectangle), which had been divided and sold by the late 1850s. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1950.17)

Chew and Relf did not take the suit’s implication of fraud lightly, and neither did the rest of the city’s moneyed elite. As Elizabeth Urban Alexander writes in Notorious Woman: The Celebrated Case of Myra Clark Gaines (LSU Press 2001), the lawsuit “presented a real threat, not just to the reputation of two leading businessmen, but to property ownership in many sections of the city,” as Chew and Relf had leveraged landholdings from Clark’s estate for many years. Even before Whitney and Gaines first filed suit, the business partners learned of the couple’s plans from a letter written by Whitney. Chew and Relf sued him for libel, using their influence to land him in Orleans Parish Prison for three weeks. When Whitney died of yellow fever three years later, at age 27, Gaines blamed the prison stint for weakening his constitution. Whitney’s death left Gaines alone with their three children and little money—much of their savings had already gone to legal fees—but she vowed to fight the case as long as it took.

She soon married Gen. Edmund Pendleton Gaines, who helped continue her litigation as it wound its way through the courts. Her first two major victories came in 1843 and 1858, the latter of which resulted in the Louisiana Supreme Court nullifying the 1811 will and declaring the 1813 version to be valid. Unfortunately for Gaines, this victory didn’t end her battle in court. By the late 1850s, the land that once belonged to Clark had been divided and sold, much of it to the City of New Orleans. Clark’s landholdings included large portions of today’s Broadmoor, Mid-City, and Faubourg St. John neighborhoods. In order for Gaines to reclaim what was rightfully hers, she would have to sue the city—and she did, setting off decades of additional suits and countersuits.  Gaines’s case was heard in the Louisiana Supreme Court at the Cabildo, shown here. She won two major victories in 1843 and 1858, the latter of which resulted in her father’s 1813 will being declared valid. The final verdict, however, would not come until 1891. (THNOC, 1970.15.13)

Gaines’s case was heard in the Louisiana Supreme Court at the Cabildo, shown here. She won two major victories in 1843 and 1858, the latter of which resulted in her father’s 1813 will being declared valid. The final verdict, however, would not come until 1891. (THNOC, 1970.15.13)

Part of what made this case so intriguing and complicated was that the events being addressed happened under different legal regimes. The marriage between Clark and Carrière took place when Louisiana was under Spanish rule; the 1811 will was created during the territorial period; and the 1813 will was written after Louisiana was admitted into the Union in 1812. Thus, as Gaines pursued her case, the courts had to apply and interpret not only different laws but also entirely different legal regimes based on the specific event and issue in question.

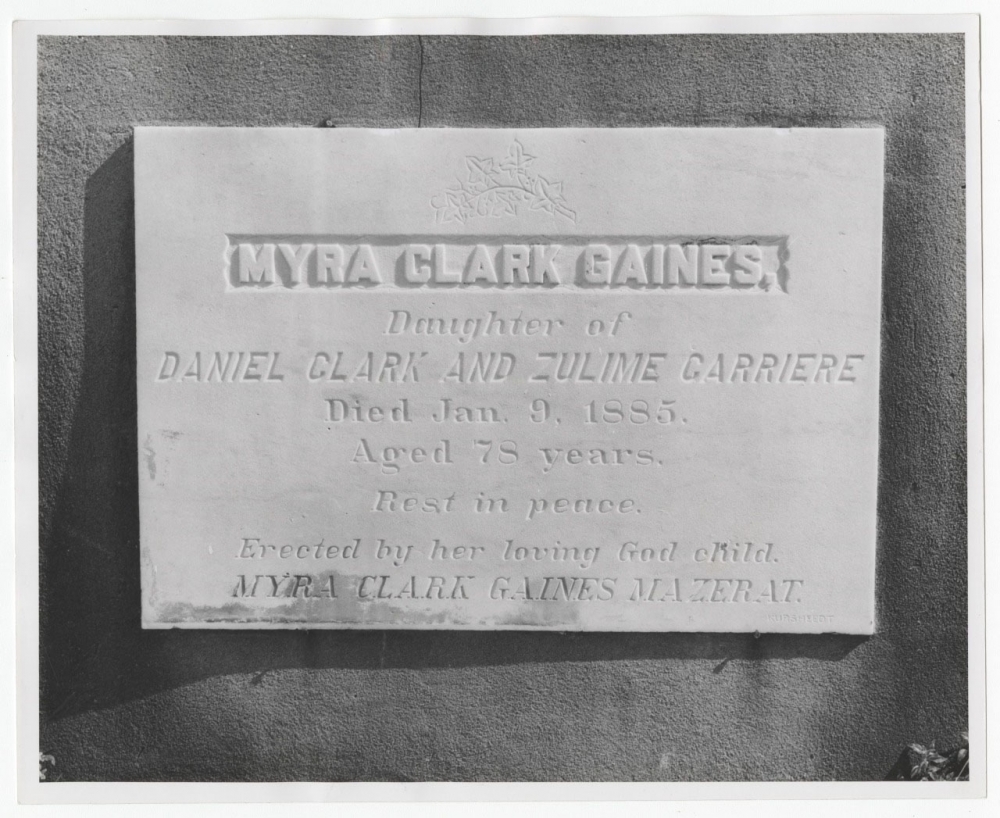

Newspapers across the country followed Gaines’s journey over the decades, calling it “The Great Gaines Case.” After 10 court filings before the Louisiana Supreme Court, 17 before the US Supreme Court, and over 70 court filings in total, Gaines won. Unfortunately, she did not live long enough to reap the benefits. She died in 1885, but the final ruling did not come until 1891. The US Supreme Court ruled in her favor, awarding her heirs $923,788, an amount just barely surpassing the legal fees she had paid over the decades. In the end, her heirs were left with just over $60,000.

Gaines’s fight rankled the highest echelons of the New Orleans business establishment, but over time she became an inspirational figure for her determination to see the case through. It was unprecedented at the time for a woman to assert her legal rights this extensively, and Gaines had on many occasions argued her own case in public court. A fixture of newspaper society columns, she used her status to advocate for women’s suffrage, joining the National Women’s Labor League in the last years of her life.

Gaines was buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. She died six years before the US Supreme Court issued its final ruling in her favor. (Guy F. Bernard Photographic Archive at THNOC, 2000.46.2.1183)

Gaines was buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. She died six years before the US Supreme Court issued its final ruling in her favor. (Guy F. Bernard Photographic Archive at THNOC, 2000.46.2.1183)

Speaking at her funeral, Rev. B. M. Palmer described the tenaciousness that defined her life and renown: “Her power of will was absolutely amazing, and I think the great lesson she teaches us in death, as in life, is how much can be done when one’s entire energies are concentrated on a single purpose—a purpose prosecuted in days of darkness and doubt. In the face of misfortune and defeat her courage remained undaunted and her resolution unshaken.”

* There are discrepancies in the reported date of Gaines’s birth. It is stated as 1806 in her Times-Picayune obituary, but other sources have put it variously between 1804 and 1807.

This is the third story in a six-month series on women's history in New Orleans. Read about the Louisiana women who fought for the right to vote here. And find out about a facinating waffle-iron lookalike tool used by the Ursiline nuns here.