New Orleans loves its Saints, but its relationship with America’s pastime dates back nearly a century prior to the arrival of pro football in the city.

New Orleans’s first interaction with professional baseball came in 1870 when the Cincinnati Red Stockings (now the Cincinnati Reds) came to play a number of exhibition games against amateur teams assembled specifically to play them. The local teams lost badly, but one enduring club was born out of these exhibition games: the New Orleans Pelicans.

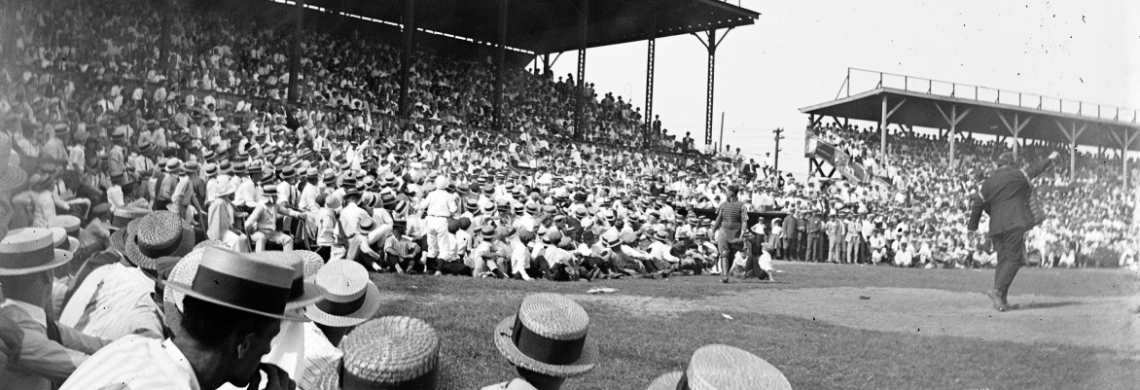

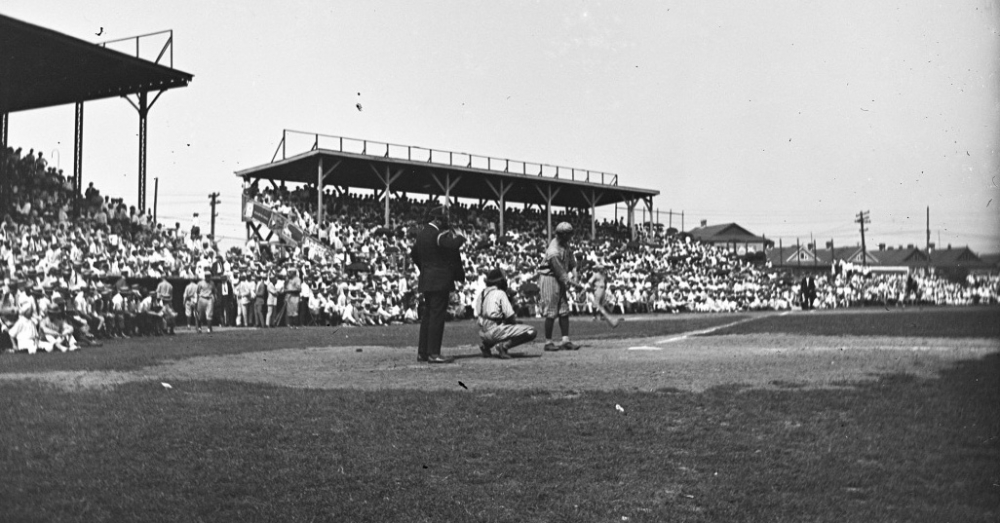

A player steps up to bat at Heinemann Park, later known as Pelican Stadium, around 1920. The stadium was located at Tulane and South Carrollton Avenues. (THNOC, gift of Waldemar S. Nelson, 2003.0182.459)

When the Pelicans—the city’s first pro baseball team—made their debut in 1887, their enterprising 27-year-old captain, Abner Powell, played an important role in cleaning up the ballpark atmosphere and transforming it into what we know to this day.

The Pelicans began play in the independent Southern League, which struggled financially and only completed a full season four times between 1887 and 1900. Powell, who maintained a player/manager role with the Pelicans until 1899, and became a part-owner in 1894, played an outsized role in keeping the league afloat. At one point he had an ownership stake in four Southern League teams.

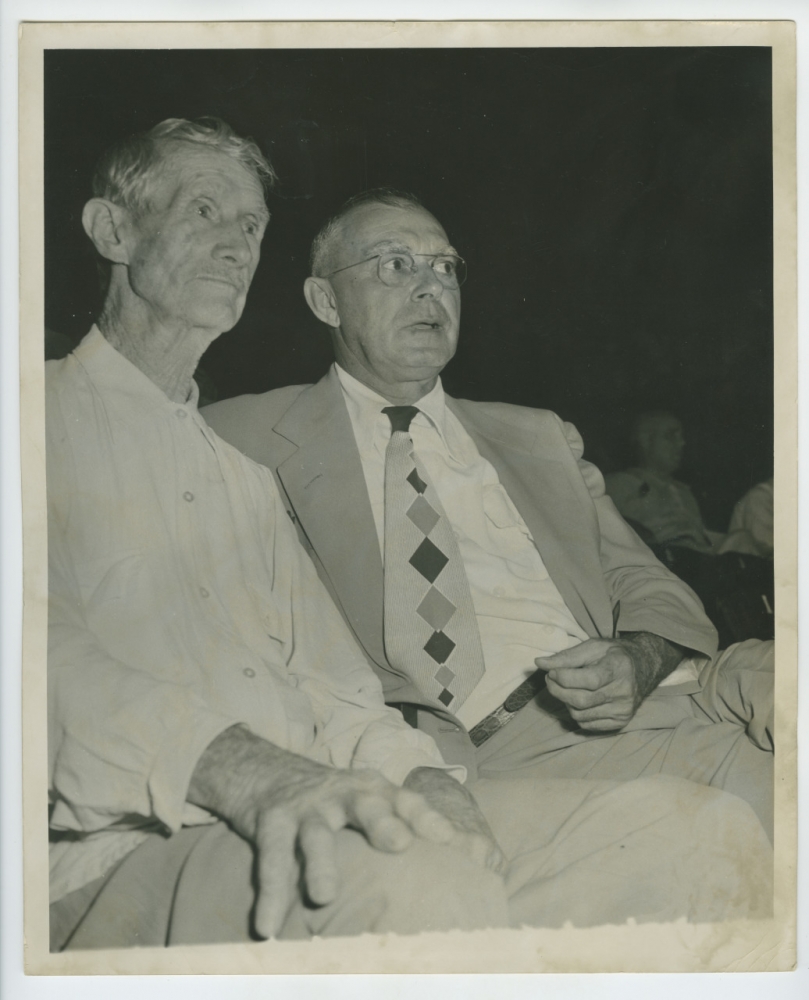

Abner Powell (left) lived out his life in New Orleans and maintained a close relationship with the Pelicans in his later years. He is pictured here with Larry Gilbert, a former major-leaguer who signed with the Pelicans in 1919 and became a player-manager in 1923. (THNOC, gift of Mark Cave, 2018.0558.4)

After the league finally collapsed, Powell helped found the new independent Southern Association in 1900 with the Pelicans as a charter member, and the team stayed in the league for most of its existence, until they left New Orleans for Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1960.

In addition to his contributions to the league, Powell proved to be an innovator for the game in general. He convinced team management to institute regular “Ladies’ Days” beginning on April 28, 1887, where women would receive free admittance. Powell’s gambit paid off in boosting attendance and opening the game up to a wider fan market. Teams throughout the country copied the idea. Powell also introduced such game-changing innovations as the detachable rain check and the use of a canvas tarpaulin to protect the infield during rainstorms.

A young couple poses at Gentilly Park during the 1920s. In addition to professional Negro League baseball teams, the black community in New Orleans fielded neighborhood squads that faced off in intracity competitions. (THNOC, 2013.0074.2.39)

The sport remained segregated in New Orleans throughout the Pelicans era, but the city has a deep black baseball tradition. Independent African American teams were active in New Orleans as early as the late 1860s, and New Orleans fielded a team—the Unions—in the short-lived but first-of-its-kind Southern League of Colored Base Ballists in 1886. During the 1880s, the New Orleans Pinchbacks—named after P. B. S. Pinchback, a black man who served briefly as governor during Reconstruction—were considered one of the best teams in the South.

The establishment of the Negro Southern League (NSL) in 1920 kicked off a new era. The original NSL remained in existence until 1936, and a second one formed in 1945 and folded in 1951, four years after Jackie Robinson broke the major league color line. Even Louis Armstrong, an ardent fan of the game, owned a team, which he called the Secret Nine (although the team was better known for its pristine uniforms than its skill). In 1931 Satchmo attended a doubleheader at St. Raymond Park and struck out the ceremonial first batter with much fanfare.

Louis Armstrong’s Secret Nine players, and their pristine uniforms, are shown here in 1931. (The William Russell Jazz Collection at THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.385.358)

New Orleans has also seen a few local ballplayers hit it big. Shoeless Joe Jackson played for the Pelicans in 1910 before eventually finding a home with the Chicago White Sox. Gretna’s own Mel Ott, despite standing a mere five feet, nine inches tall, became a giant in the sport (both figuratively and literally) as a member of the New York Giants. Future all-stars Rusty Staub and Lance Berkman honed their skills here—Staub as a student at Jesuit High School of New Orleans and Berkman with the New Orleans Zephyrs in the late 1990s.

The 1910 Pelicans, shown here, won the Southern Association championship. The team featured Shoeless Joe Jackson (pictured wearing no. 12), one the era’s best players. In 1919 Jackson became infamous as part of the Chicago “Black Sox” squad that allegedly threw the World Series. (courtesy of S. Derby Gisclair)

Even during the years the city lacked a professional baseball team, big league ball clubs would hold exhibition games on a makeshift field in City Park, and later the Superdome. The New York Yankees even considered playing some regular season games at the new venue while Yankee Stadium was under construction in 1975. At the time, local boosters were trying to lure a permanent team to the Crescent City, according to the New York Times. The New York Mets, Chicago Cubs, and San Francisco Giants—whose roster featured New Orleans native Will Clark—also participated in exhibition games in the Superdome between the 1970s and ‘90s. Alas, a major league team never materialized, though a Triple-A version of the Pelicans resurfaced for one year in 1977.

Professional baseball returned to New Orleans when the Zephyrs—later the Baby Cakes—arrived from Denver, after the Colorado Rockies were established in 1993. The team left for Wichita, Kansas, after the 2019 season, leaving another baseball-sized hole in the sports fabric of New Orleans.

For more on the history of baseball in New Orleans, visit THNOC's current exhibition Crescent City Sport: Stories of Courage and Change, which explores the history of sports in New Orleans through 20 different narratives. The exhibition is open through March 8, 2020. Admission is free.

For more on the history of baseball in New Orleans, visit THNOC's current exhibition Crescent City Sport: Stories of Courage and Change, which explores the history of sports in New Orleans through 20 different narratives. The exhibition is open through March 8, 2020. Admission is free.