To Carnival connoisseurs, it’s a well-worn origin story—how H. Alvin Sharpe changed Mardi Gras forever with a flick of the wrist.

An artist and artisan of many media, he’d been peddling a big idea for five years with no luck, pitching festivals across the country and abroad on a new type of commemorative keepsake. Taking one last swing, he wrote a letter to one of the city’s elite Carnival krewes, Rex, describing his vision: “I have designed some very beautiful ‘doubloons’ that can be coined in soft aluminum (gold or bright) very cheaply. I feel that these ‘Rex coins’ would be a sensation as a memento of Mardi Gras.”

The Rex organization responded, and in December 1959 Sharpe walked into the office of Rex’s captain, the prominent financial manager Darwin Fenner, ready to give up the grind if it didn’t work out. “Truthfully, I had tried to interest everyone I could think of in this idea of the doubloon,” he told the Times-Picayune in 1965. “When I went to the captain of Rex that day, I said, ‘This is my last stop.’”

Fenner was interested, but he expressed concern about the prospect of tossing metal discs at parade-goers. “They were afraid of getting sued,” Sharpe said. In response, the artist “tossed a handful in his [Fenner’s] face, to show you couldn’t get hurt.” Sharpe’s proof of concept prevailed. “He took one look and bought the idea.”

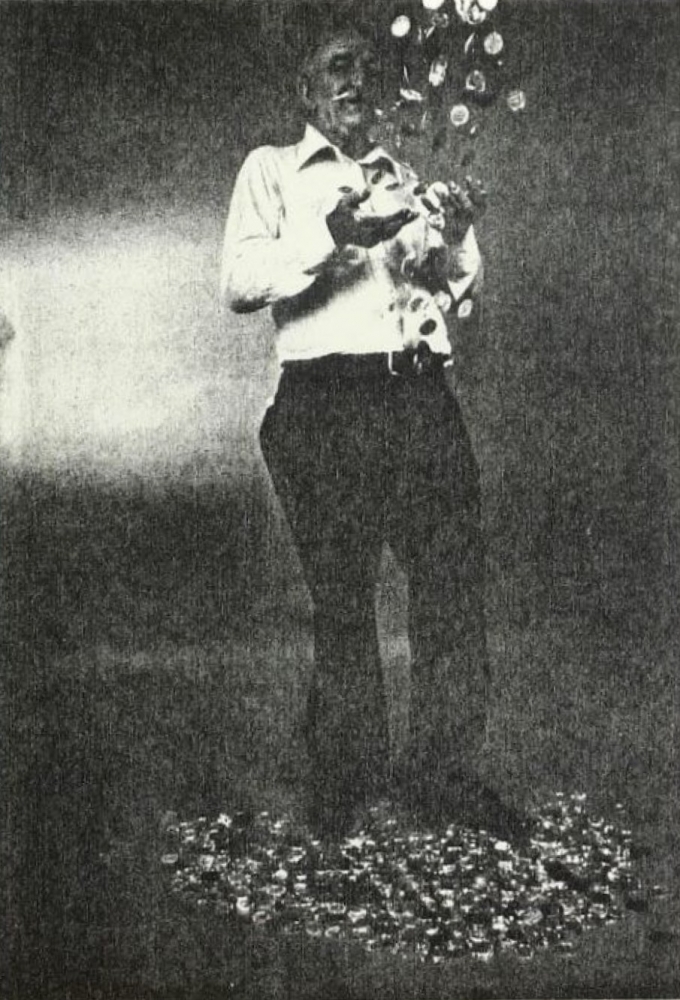

Sharpe’s inaugural medallion for Rex, in 1960, doubled as the world’s first Mardi Gras doubloon. An explosion of signature throws across the city’s Carnival krewes followed. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1965.4.1)

Rex ordered 80,000 aluminum doubloons for Mardi Gras 1960, as well as 29 silver ones for special members of the krewe, and they were an instant hit. One of those inaugural doubloons, as well as Sharpe’s artist proof and Rex manuscripts about the new throw, is now on display at the Williams Research Center as part of Fit for a King: The Rex Archives at THNOC, a companion exhibition to Making Mardi Gras at 520 Royal Street.

Within just a few years of the throw’s debut, virtually every big krewe in the city was tossing doubloons, many of them featuring Sharpe’s hand-engraved designs. A thriving collector’s market emerged, complete with fan clubs and annual checklists accounting for every doubloon on offer. Doubloon mania grew throughout the 1960s and ’70s, inviting both adults and children to join the hunt; today, many an attic in greater New Orleans has a binder or two filled with the spoils carefully preserved between sheets of plastic. Active collectors remain, as well. The Crescent City Doubloon Traders Club meets for swaps eight to 10 times a year, and Sharpe doubloons, artist proofs, and etchings routinely sell on eBay.

Within years of the doubloon’s debut, a thriving collector’s market emerged, seen in this price guide from 1972. Also common were annual checklists to help doubloon hunters keep track of their finds. (Photograph courtesy of eBay)

What’s more, with the invention of the Mardi Gras doubloon, Sharpe catapulted the entire notion of signature throws into mainstream popularity. Previously, throws consisted of beads and trinkets with no distinguishing marks particular to each krewe. One exception was Zulu: the club introduced its signature throw, coconuts, in 1910, but they were undecorated (and untapped, making them far heavier than today’s coconuts). It’s unclear when the club started adorning the “golden nuggets” with the Zulu name. Now, krewe-specific medallions, cups, shoes, purses, and more comprise a huge proportion of the millions of throws tossed from floats in a typical Carnival season.

To lovers of Carnival lore, Sharpe is fondly known as the “father of the Carnival doubloon,” and rightfully so. But the artist was much more than the trinket that earned him a place in the history books, and his drive in selling the idea wasn’t born of hucksterism or gimmickry. In addition to being a painter, engraver, and master of intaglio (the 6,000-year-old process of stamping a design in relief from a hand-incised die), Sharpe was a seaman, world traveler, poet, philosopher, and autodidact. A true renaissance man, he had an insatiable appetite for experience and knowledge. He was an antimaterialist who valued craft and curiosity over fame and fortune, working deep into the night to realize a design or write a poem.

“He is the only person I have ever met in my 53 years who was a genius,” said Dukes Richardson, Sharpe’s close friend, following the artist’s death in 1982. “If you ever met him you would have to say that he was the most interesting person you had ever met.”

Out of the hills, over the seas, and into the Crescent

As a young artist in the 1930s, Sharpe hustled work wherever he could find it, selling etchings and paintings to riverboats and hotels, painting the dome of the New Orleans Board of Trade Building, and, as seen here, painting the Mississippi River from the sky for an airline publicity stunt. (Photograph courtesy of NOLA.com | The Advocate)

Herbert Alvin Sharpe was born January 20, 1910, in Corbin, Kentucky, a small town just outside Daniel Boone National Forest. The self-described “hillbilly” was always drawn to art and adventure, picking up woodcarving and playing hooky from school to pursue his own interests out of doors. He was “one of those backwoods boys who used to jump out the one-room schoolhouse window to go look at rocks with a magnifying glass,” wrote Nancy Weldon after interviewing Sharpe in 1981, near the end of his life, for Arthur Hardy’s annual Mardi Gras Guide. “He kept his gun, knife, and camping gear hidden outside.”

“Sometimes they wouldn’t find me for two days,” Sharpe told her.

He left school at 13 and worked writing stories for the local newspaper, but the call of the wild persisted. In particular, he was fascinated by the ocean, and at age 14 he made his way to New Orleans in search of the seafaring life. “You can’t sail a ship in the hills of Kentucky,” he said. Securing work on a cargo ship, he sailed around the world for the next seven years. During that time, he used the long stretches at sea to read, write poetry, and make art.

“He read everything,” wrote Kenneth Gormin, a friend and public relations specialist who contributed the preface to Sharpe’s first collection of poetry, The Gist of Life: Four Lines at a Time, published in 1974. “His taste was catholic—books about travel and adventure, art, coinage, commerce, history, religion. It didn’t matter—Al read what he could get his hands on when he was at sea or on land.”

His early seafaring years also gave him his name, in a way. Sharpe was tall (ships’ registers list him as an even 6 feet) but slight of frame; when he joined up, he was probably the youngest person on many a crew, which earned him the unwelcome nickname “Little Herbie.” After getting into several altercations about it with his crewmates, he adopted his middle name and relegated the “Herbert” to an initial. Decades later, his “HAS” artist’s stamp graces millions of doubloons worldwide.

Sharpe cut his teeth as an artist with seascapes, seen in his 1953 painting Schooner at Sea. As a boy he dreamed of life on the water, and at age 14 he came to New Orleans to make it happen, hopping on and off cargo ships for the next seven years. During and after his WWII service in the Merchant Marine, he traveled to Fiji, Scotland, Japan, and other far-flung locales. (Image courtesy of AskArt.com)

Sharpe worked in the modest medium of pencil sketches at first, but he soon found that his aptitude as a draftsman could support a career. While in port, he sold his drawings of ships and seascapes to tourists. “I was getting $25 for a pencil sketch when the best French artist might get $50 for an oil painting,” he said. “That was big money.”

Another side hustle was gem prospecting. A lover and student of rocks since childhood, he learned by reading books and listening to fellow sailors in the game. “He uncovered finds of opals in dry riverbeds in Australia,” Gormin wrote. “He traded emeralds, rubies, and other rare gems with Russian, Norwegian, and Greek seamen.”

More than precious stones, though, Sharpe “prospected for history . . . and learned much about mankind,” as Gormin put it. “It wasn’t enough to read about them.” He was driven by pure lust for life and a desire to know the world and its people.

At various points during his teens, he enrolled in three different art schools but was “thrown out the first day,” he said. “Every school I went to, they’d all turned modernist”—and Sharpe was thoroughly traditional in his style.

Those formative years gave Sharpe the confidence to establish himself as a working artist after he returned to New Orleans in 1931. Initially, he was “just passing through” between stints at sea, but then a friend invited him to play bridge in Lakeview, where he met 20-year-old Beverly Henderson. It must have been some game. “By about four in the morning, I’d proposed,” he said.

Putting down roots and painting in the air

When Sharpe pitched Chicago and Southern Air Lines to paint the entire Mississippi River from the sky in 1937, they said yes, and the ensuing 14-hour itinerary broke “something of a record.” (Photograph courtesy of NOLA.com | The Advocate)

By 1934, Sharpe not only had a baby daughter, Lynn Joanne, he’d also become a rising talent in the commercial art world. The Roosevelt Hotel bought a number of his etchings to adorn its halls (by the end of his life, according to his obituary, he’d placed approximately 600 of his works there), and his paintings of ships decorated local riverboats.

Early on Sharpe displayed a knack for getting the attention of powerful people. In 1937 he approached an executive for Chicago and Southern Air Lines to propose a publicity stunt: painting the Mississippi River from the air. The airline accepted, and on the morning of April 14 he boarded a Lockheed Electra at Shushan Airport (now the New Orleans Lakefront Airport), “donning his smock, spreading his canvas and placing his brushes and paints and palettes before him,” the States-Item reported. Sharpe completed his trip up the Mississippi to Chicago and back in 14 hours—six hours there, a two-hour stop to refuel, and six hours back—which, at the time, was “something of a record,” according to the States-Item.

The same year, Sharpe completed the biggest commission of his young career: eight 12-foot-high murals radiating around the domed skylight of the historic Board of Trade building at 316 Magazine Street. Sharpe was paid $5,500 for the project, which took three months to finish; each mural depicted a different New Orleans industry, such as sulfur, coffee, shipping, telecommunications, public utilities, and transportation. Upon completion, though, the scaffolding was removed so quickly that Sharpe never had a chance to sign his name.

Sharpe spent three months working on the eight industrial murals that still encircle the dome of the Board of Trade building on Magazine Street. The scaffolding was removed so quickly, however, that he never had a chance to sign his name, and his painting of the murals was forgotten until shortly before his death. (Photograph by Keely Merritt, THNOC)

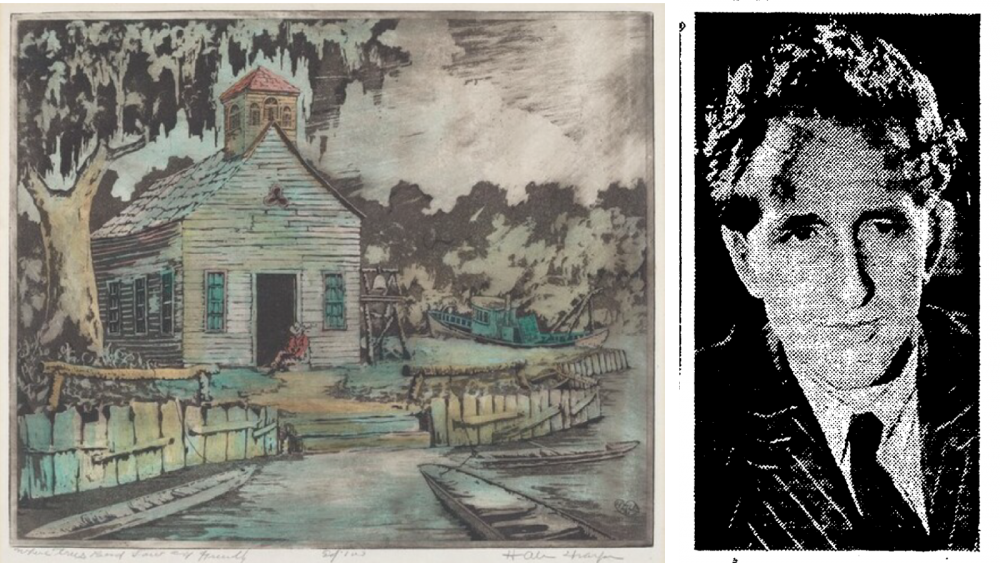

Sharpe chased opportunity, but he seemed to shy away from acclaim. He became the toast of the Spring Fiesta when his etching Where Trees Bend Low and Friendly won top prize at the festival’s art competition in 1941. Speaking to an Item-Tribune reporter, he was almost apologetic: “It’ll be years yet before I’ll have anything really worthwhile,” he said. “I don’t see why anyone should want to take a picture of the etching or of me either. I’ve got at least a couple of decades of hard work before I’ll begin to have anything on the ball.”

Sharpe’s words were, in retrospect, prescient. He would spend the next few years in the US Merchant Marine, serving in World War II. One account claims that he saw action in both the Atlantic and the Pacific arenas, another that he helped smuggle Jewish refugees out of Europe. One night, he said, his dead sister came to him in a dream and told him to get up for his shift on board. Even though he had hours until his duty started, he did as she said; shortly afterward, a torpedo blasted through his cabin. Following the war he remained a seaman for at least four years, making stops in Scotland, Fiji, Panama, and Japan.

His wandering continued in the 1950s, as he took prospecting trips for gold out West with a New Orleans friend named Gaspar. When not traveling, he took a spin as a furniture maker, selling “tap-root tables” made from slabs of tree stumps.

Sharpe’s etching Where Trees Bend Low and Friendly (left) won him top prize at the art competition of the Spring Fiesta in 1941. Of the publicity he received for the prize, including a short feature in the newspaper (right), Sharpe expressed modesty, saying he didn’t know why anyone would want to take his or the etching’s picture. (Left: image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art. Right: photograph courtesy of NewsBank)

How Sharpe’s family felt about his many extended excursions isn’t part of the historical record: neither Beverly nor the couple’s daughter ever spoke about Sharpe on the record except after his death. Beverly described him as “a unique man” and said “there was really nothing he couldn’t do,” but that statement and a couple of reported anecdotes comprise the extent of her public commentary about her husband. City directories show that she took a job as a saleswoman at D. H. Holmes Department Store in 1945, during Sharpe’s WWII service, and she seems to have held the job (whether continuously or in stints) through the mid-1950s. She died in 1993. Lynn Joanne Celestin became a well-loved piano teacher and mother of six children; she died in 2013.

Sharpe had taught himself intaglio engraving back in the 1930s, but he doesn’t seem to have deployed the skill at any government-run mint. Sharpe tried for years to sell his idea of aluminum doubloons, but “nobody listened,” he said—no one until he met with the captain of Rex that day in 1959.

Minting a legacy

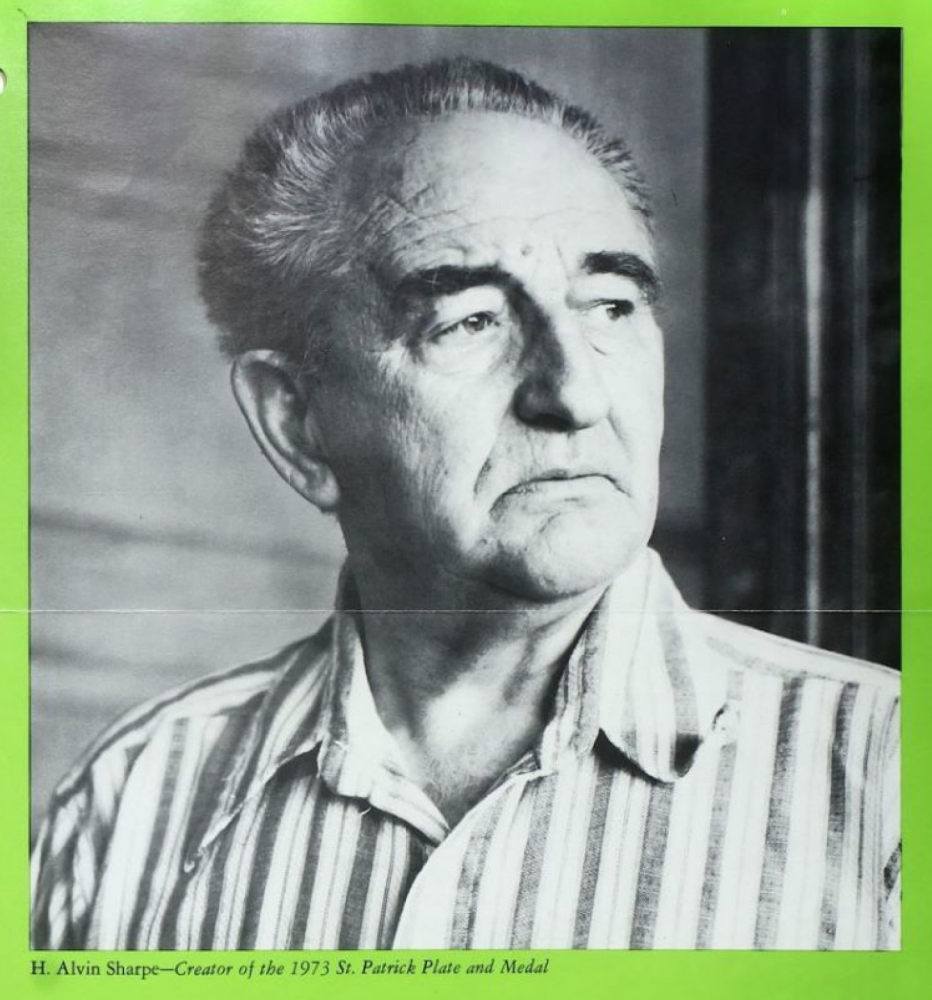

The immediate success of the Carnival doubloon changed the course of Sharpe’s career, allowing him to work as a medalist for the rest of his life, and helped spur a renaissance in collectible coins and medallions nationwide. He’s seen here in a 1973 portrait for the Hamilton Mint, a collectible-coin company. (Photograph courtesy of University of New Orleans, Earl K. Long Library Louisiana and Special Collections, Charles V. Booth Collection)

The idea of doubloons arrived so late in the planning of Carnival 1960 that Rex didn’t have a chance to alert even the riders in the parade, much less the press or public. On Mardi Gras Day, Sharpe was in the Rex queen’s viewing stand on St. Charles Avenue, where word of the new trinket started spreading even before the parade arrived.

“There were reports coming in from Jackson Avenue that the maskers were throwing something new,” Sharpe recalled. “Some of the maskers were so excited by the doubloons that they threw them all early in the parade without saving any for later. . . . Before the day was over, they had caused a sensation.” Over the following months, he received calls from around the country—people asking how to get their hands on a doubloon.

Later that year, in response to the success of the new throw, Sharpe was made a founding partner in Educoin, a new doubloon-production company. His role, of course, was to create the designs, and Educoin facilitated the outsourcing of mass production to facilities in Ohio and Mississippi. In 1964, seeing a hole in the market, the president of a New Orleans gear-making company, John Barr, created Barco Mint, the city’s first doubloon factory. Rex moved its business over from Educoin, a move that Sharpe regarded as a betrayal at the time. “I’ve felt contempt but not bitterness,” he said decades later of the situation.

The craze for doubloons extended beyond Mardi Gras and its fans. Commemorative coins experienced a surge in popularity nationwide, with a handful of commercial mints around the country cranking out decorative medallions marketed to consumers as keepsakes and investments. “There’s a renaissance in medals now, and it started because of New Orleans,” Sharpe said in 1976, a banner year for commemorative coins because of the bicentennial of the United States’ independence.

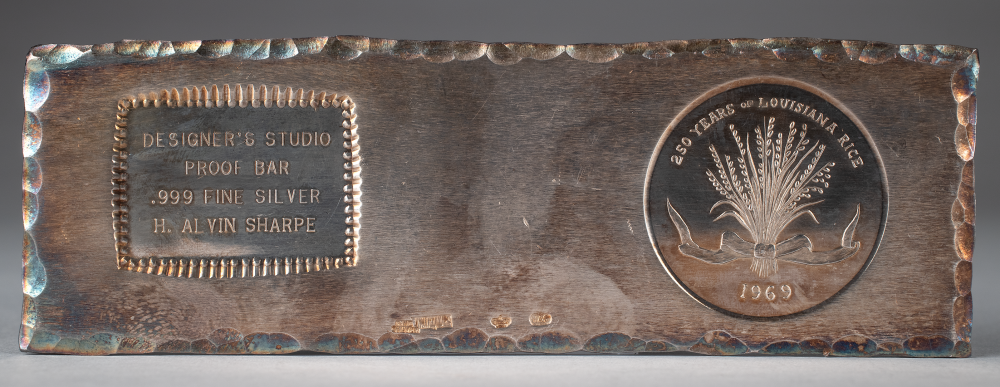

Doubloons became a popular commemorative keepsake outside of Mardi Gras throughout the 1960s,’70s, and ’80s. This artist’s proof bar shows Sharpe’s design for a 1969 doubloon in honor of Louisiana’s rice industry. (THNOC, gift of Paul J. Leaman Jr., 2003.0181.3)

These commercial mints typically offered subscription services for devoted collectors, and from 1969 to 1971 Sharpe did so as well, through the newly created Louisiana Medallion Society. Sharpe functioned essentially as a one-man mint, hand-casting “fine silver medallions” that depicted popular people and scenes from local history—La Salle claiming Louisiana for France, Bienville’s founding of New Orleans, the Battle of New Orleans.

After Educoin folded in the mid-1970s, Sharpe worked for a stint at the newly created New Orleans branch of the Hamilton Mint, a commemorative-coin company, but for the most part he remained a freelance artist, and he preferred it that way. He worked freehand, often doing his metal etchings straight from his imagination after hours spent waiting for inspiration to strike. A night owl and chain-smoker, he would hole up in his West Bank office, which was cluttered with tools, books, and papers. Friends, journalists, and collectors frequently popped in, and he was always happy to stop his work to talk or spin a yarn.

As doubloons’ popularity continued, so did Sharpe’s. Profiles of him or mentions of his work appeared in local media every few years during the last two decades of his life. (Photograph as seen in New Orleans magazine, 1977)

As his media exposure grew over the 1960s and ’70s, Sharpe spoke about his craft with the reverence of a true believer and a strong dose of humility. He often rebuffed accolades about being the “inventor” of the doubloon: “Doubloon? Yeah, I was the stupid ass who started that,” he told New Orleans magazine in 1977. “The Romans and Greeks had this idea many years ago,” he said in another interview. “I just revived it.”

Indeed, it was reading about early Western civilization while in his mariner days that first planted the seed of the idea. “The ancients had made medals representing generals and leaders and threw them to the people,” he said. He often called doubloons medallions, which is technically what they are—historically, “doubloon” refers to a Spanish gold coin.

Though they were undoubtedly trendy at the time, Sharpe saw doubloons as timeless. “First, and above all else, a medal should be good art in the classic sense and not gimmicky or faddish,” he said. “Medals, after all, will still be around as a witness to our civilization perhaps thousands of years from now, longer than most other art forms.”

Sharpe believed that medals’ durability made them a superior medium for documenting human civilization. Sharpe was commissioned to design a medallion commemorating the Chucalissa mound complex in Memphis, Tennessee, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. (THNOC, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Thomas E. Weiss, 1999.76.13)

While he acknowledged that the aluminum of most Carnival doubloons would degrade more easily than medals made of silver or copper, he maintained that doubloons provided a material record of human civilization superior to all other media. “If you preserve with a photograph or print, in a few years it will be gone,” he said in 1981. For this reason, in part, his Zulu doubloons spotlighted a different African tribe or kingdom each year, showing a member wearing their finery in profile. Many of Sharpe’s other krewe designs depict historical figures, and he took particular pleasure in designing for the Krewe of Poseidon; each year’s doubloon featured a different type of historical ship.

“Human nature doesn’t change,” he said. “People have been collecting coins and medals for over 2,000 years. They always will, too. You never see a medal in a garbage can, do you?”

Putting down his chisel

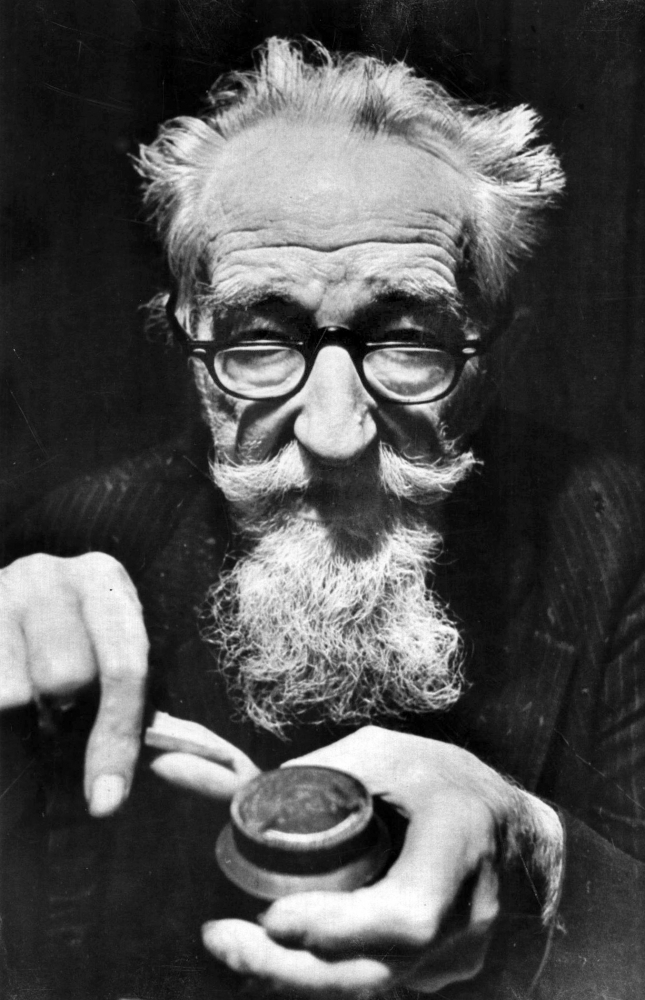

With a St. Nicholas beard and failing eyesight, Sharpe lived his final years in his daughter’s house on the West Bank. (Photograph courtesy of NOLA.com | The Advocate)

In the final years of his life, Sharpe went almost completely blind, his field of vision reduced to a slit as thin as the medallions that made his name. Mardi Gras Guide reporter Nancy Weldon remarked that he had to turn his head this way and that during their conversation to get a composite picture of her. His long white beard was thin and tussled, and one 1977 account mentioned his “toothless gums.”

Sharpe was living with his daughter on the West Bank and was suffering from an undiagnosed, terminal illness. He had refused to see a doctor his entire life and didn’t see the need to start then. Speaking in September 1982, he knew his time was limited: “I was born on the night of Halley’s Comet,” he told Dana Standish of Gambit. “Legend has it that those born on that night will live until the comet comes again to take them away. . . I’m not going to make it that long.”

He made it just long enough to see the New Orleans Board of Trade rediscover and commend him for his painting of the murals, five days before his death. Sharpe had devoted the last half of his life to stamping medals in part because he believed they would last for the ages—tiny metal monuments bearing his artwork and initials. Facing death, however, Sharpe seemed to realize that all things must pass. “I don’t know whether I’ll go down in history as an artist or not,” he said in his last interview. “I’ll probably go down as just a deluded old man.”

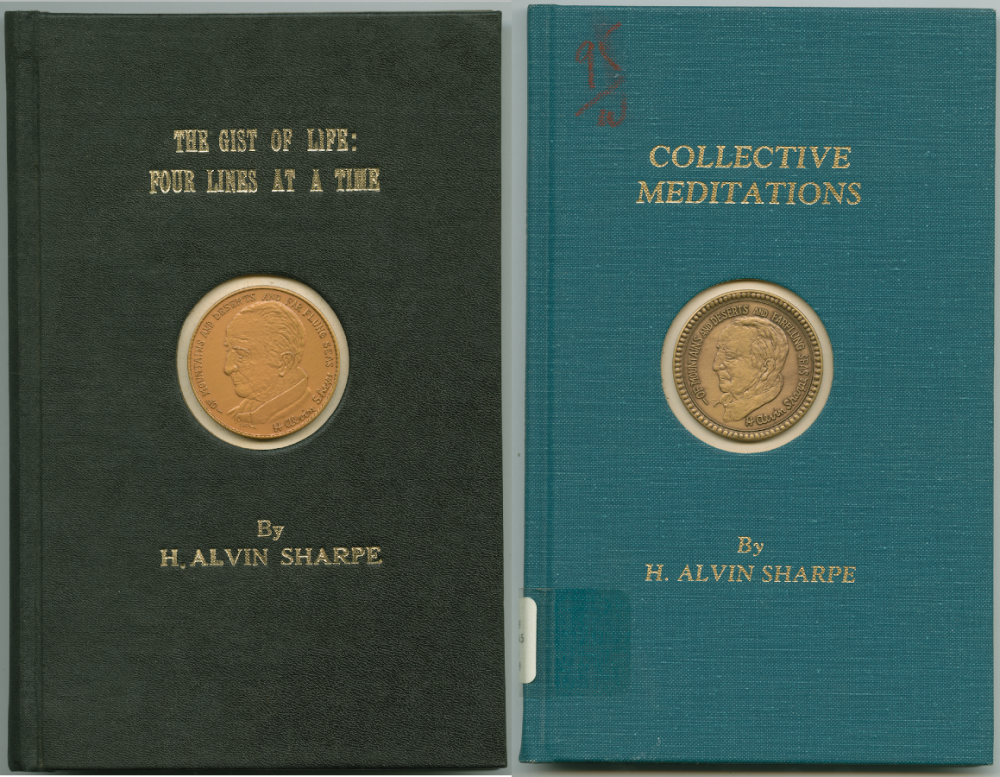

A lifelong amateur poet, Sharpe’s media-connected friends helped him publish 50 of his poems in two bound editions, first in 1974 with The Gist of Life: Four Lines at a Time and again in 1979 with Collective Meditations. (THNOC, 2001-120-RL.3, 86-388-RL)

Such concern with legacy must have been natural, given his condition, but it stands at odds with the life he led. In his youth he followed the wind, hopping off ships to explore any port of call that caught his interest. Always privileging the journey over the destination, he seemed to value each day as an opportunity to learn, create, and worship the wide world.

“He is what many of us would like to be—a contributor to the beauty, the art, and the understanding in a world that knows so little peace and where so many think only in terms of what its dollar value may be,” wrote Kenneth Gormin.

This deep reverence for human experience is best found in Sharpe’s poetry. He never considered himself a poet, though he amassed over 500 works; rather, he claimed to be a lifelong sufferer of “severe reoccurring attacks of ‘versitis.’” Friends helped him compile and publish 50 of his poems in 1974, with a second edition published as Collective Meditations in 1979. They range from lighthearted—the delight of eating “old-fashioned cheddar cheese” or the pleasure of spotting a pretty girl—to moralistic, such as one poem denouncing the ignorance of bigotry. Sharpe was not a religious man in the traditional churchgoing sense, but he was spiritual, and poetry provided a means to express his deepest convictions. In “Ten Talbas’a,” he proclaims his belief in the godliness of “every living creature” and the responsibility of each person to honor their existence by making something beautiful of it.

I believe in a God universal,

Omnipotent in life, space and time.

His goodness encompassing and ageless,

This God, this God of mine.

And ours a single obligation

(We are his potters at hand)

To shape our life, (his vessel)

And place upon it his brand.

Sharpe created this medallion to adorn the cover of his 1979 book of poetry, Collective Meditations. The inscription reads, "Of mountains and deserts and farflung seas," along with his artist's signature. (THNOC, 86-388-RL)