“It’s ya boy, Action Jackson!”

To New Orleans lovers in radioland, those five words were an instant mood boost. Charles M. Jackson Jr., known far and wide as DJ Action Jackson, was a devoted chronicler of the city’s community-based Black parading groups. A longtime club and radio DJ, Jackson brought the streets of New Orleans to the world through his WWOZ-FM web show, Takin’ It to the Streets, as well as his weekly on-air radio show. Social aid and pleasure clubs, benevolent associations, Black Masking Indians (a.k.a. Mardi Gras Indians), Baby Dolls, and brass bands all knew him and graced his microphone over the years, and his show archive stands as one of the greatest bodies of contemporary documentary work related to Black New Orleans culture.

Jackson held court in the WWOZ studio every Thursday afternoon, no doubt giving shout-outs to friends and fans across the city and beyond. (Photograph by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee, courtesy of the artist)

Jackson died in August 2021, following complications from colon cancer, leaving New Orleans and the parading scene without one of its biggest champions. Among other relatives, he is survived by his son, Charles Jackson III, and his daughter, Chantrell Trahan.

“You know like they say, naturally N’awlins? [He was] like that, absolutely,” said Jackson’s younger brother, the entertainer Roland “DJ Ro” Watson. “Love hanging in the hood. Love the culture, going to second lines, block parties, birthday parties, playing dominos in the garage with his boys.”

A New Year’s baby, Jackson would have turned 60 this New Year’s Day (2022), no doubt preceded by “party after party after party leading up to the big birthday,” DJ Ro said, speaking in mid-December. “It’s that time period now, so he’s very much in the mind. I’ll think of something and say, lemme call Action, and then realize he’s gone.”

A loving documentarian of New Orleans Black parading culture, Action passed away from colon cancer on August 8, 2021. (Photograph by Judy Cooper, courtesy of the artist)

Jackson was born in the Ninth Ward and lived there until his death. As an adolescent, he avidly followed the rise of DJ culture, forming a DJ crew with Slick Leo, LBJ, and Slick Mike. They had a standing gig at the neighborhood skate rink—“Action Jackson on the microphone, Slick Leo on the turntables,” Ro said. As MC, Jackson would hype the DJ and pump up the crowd with his signature rap:

Well I got a rhyme that’s right on time,

but first I need your zodiac sign—

so what’s your sign?

“People would go crazy, shouting out their sign, and even some celebrities started doing that,” Ro said.

DJ Ro was inspired by his older brother’s moxie and love of music and entertaining. “They had the big speakers on their car, pulling up all happy to go to the gig, spread love to the people and play music,” he said. “Something just hit my soul, like, ‘man, that’s—I want to do that.’ I’m a DJ because of my brother.”

Action Jackson interviews Angelina “Mrs. Divine” Sever of the Divine Ladies Social and Pleasure Club at the club’s parade in 2015. (Photograph by Judy Cooper, courtesy of the artist)

Jackson joined the National Guard after high school and stayed in the job for a decade, doing DJ work in nightclubs on the side. He also worked in law enforcement and as a limousine driver. A fixture on the second line scene, he was always at the beginning of the parade to watch the club members come out the door in their finery.

“He’d be there headfirst: get his ‘green bottle,’ we call it—Heineken—and go talk to the people,” Ro said.

Ecumenical in his love for the city’s social aid and pleasure clubs and benevolent associations, Jackson never belonged formally to a club, but he and his brother reigned as kings of the Ninth Ward–based Big Nine in 2004 and 2006, and he masked Indian with the Ninth Ward Hunters for three years in the late 1980s and early ’90s.

It was in the 1990s that Jackson’s career in broadcasting began, first through informal interviews on the local hip-hop and R&B station Q93. Ro was a DJ there (and remains so), and Jackson would visit the studio or call in to chat.

“Generally me and [DJ] Slab 1 just talked on Fridays, and one day he said, ‘What are you doing this weekend?’ and I said, ‘I’m going to the second line,’” Jackson said in a 2020 interview with The Historic New Orleans Collection. “I’d say the club [that was parading] and where the parade was going, and then [eventually] the people started calling in, saying, ‘Where the second line at this week?’ And so we started doing it every week.”

In 2011 he was approached by Ariana Hall and David Freedman of WWOZ to bring his unique reportage to the community radio station. Hall created Takin’ It to the Streets soon after and brought Jackson in as show host; she served as the show’s producer until August 2016. Every week during second line season, he interviewed leaders of parading clubs to discuss their history, style, music, and minutiae. “It became very popular,” Jackson said. “I noticed a lot more people at the second lines, including the paparazzi—which, in my mind, was a good thing, to expose what was going on to the world.”

Second liners, accompanied by a brass band, dance down North Claiborne Avenue following Jackson’s funeral. (Photograph by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee, courtesy of the artist)

At the time, access to information about club parades was “very difficult to find—you had to be a part of the scene,” said Judy Cooper, a longtime second line photographer and friend of Jackson’s, who invited him to contribute an epilogue to her book Dancing in the Streets, published in 2021 by THNOC. “If you wanted to know where the next second line was you had to get a route sheet passed out at that Sunday’s second line. Or you had to be on the email list of the Backstreet Cultural Museum.”

Jackson also had a weekly on-air DJ slot for WWOZ, initially from midnight to 3 a.m. and eventually settling on Thursday afternoons. Often, he’d host club leaders, musicians, or anyone he wanted live on the air, between sets of New Orleans funk, rhythm and blues, soul, swingout, and brass band music.

Jackson’s gift, DJ Ro said, was to make people feel at ease enough to open up about their traditions, feelings, and second line practices. “A lot of people don’t wanna go on the radio, be on camera or anything. He’d say, ‘You gotta crack the mic, speak up—this your mark.’ Some people just have that instinct that make you feel comfortable with them. And he’d convince them that what we’re about to do is going to advance your career, your organization. And not selfishly: he was connecting the dots in a visionary way to see how we can benefit off each other.”

When the pandemic hit and the city went into lockdown, taking second line parades with it, Jackson’s thoughts turned immediately to the health of the second line tradition and the needs of the club members. “This little mind that I have, it just—I couldn’t sit down,” he said in his contribution to Dancing in the Streets. “I call myself something like Paul Revere, like, ‘The second line is coming! The second line is coming!’ So when I thought about it . . . I said, let’s try to find a way to go on Facebook and show some of the video footage that we have from previous parades.”

Jackson interviews Perry “Ice Bird” Franklin of Keep ’N It Real Social and Pleasure Club in 2015. (Photograph by Judy Cooper, courtesy of the artist)

The result was Secondline Sunday, a weekly livestream showcasing videos of second lines past, centering on whatever club would have been parading that particular Sunday. Starting in the early 2000s Jackson had partnered with Costie “Mr. C” Anderson to videotape the parades, with Jackson as the live host.

“Once the clubs got familiar with us to go in between the rows of paraders, we’d get these exclusive shots,” Jackson said, “so we have all this footage that we’ve been sitting on.” Nothing could replace being at a live second line, but Jackson knew he could lift people’s spirits temporarily with a reminder of the “four hours of therapy” those parades provide. “It’s the best medicine in the world,” he said.

Jackson also kept up his podcast throughout 2020—including during his chemotherapy and radiation treatments for colon cancer—interviewing club members about the effects of the pandemic on their community. “Now I’m more concerned with the health of the people,” he said. Jackson worried about “major depression” and “financial burden” caused by the pandemic, and he became a key intermediary in local relief efforts. Working with the mutual-aid parading group Krewe of Red Beans, he helped connect local culture bearers with free home-delivered groceries, as well job opportunities for out-of-work second line musicians and craftspeople.

Jackson helps deliver free groceries during lockdown as part of the Krewe of Red Beans’ mutual-aid initiative Feed the Second Line. (Photograph by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee, courtesy of the artist)

Jackson was an ideal intermediary between the second line community and the wider world because “he lived it—that was his thing,” said DJ Ro. “Somebody who was authentic and actually out there. He bridged the gap with that.”

He lived just long enough to see the finished version of the book Dancing in the Streets. He had loaned an item to THNOC for the book’s companion exhibition—a drum belonging to his grandfather Andrew Jefferson, who played for the Olympia Brass Band—and he was able to see the show when it opened in February, but by the time it closed, in June 2021, he was too sick to attend the closing party. He spent the remaining months of his life in the hospital and hospice care. If he'd lived another month longer, he could have witnessed the official return of the second line season.

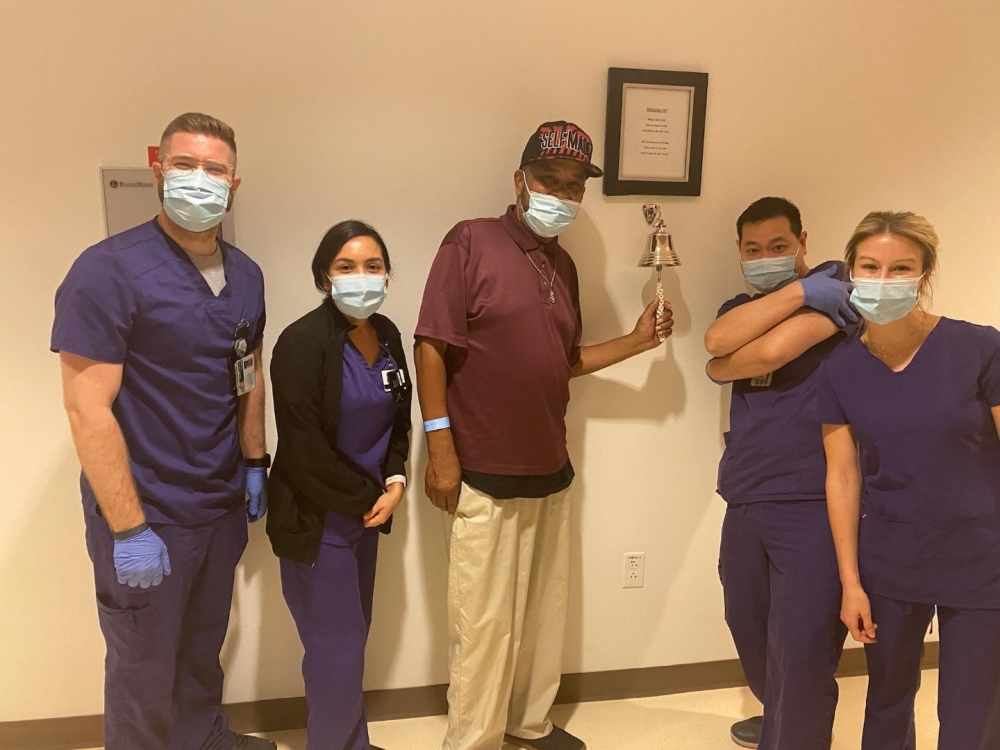

Standing with his oncology team at University Medical Center, Jackson rings the bell to celebrate the completion of his treatments for colon cancer in early 2021. Complications followed, however, and in June he was hospitalized, later transferring to hospice care. (Photograph courtesy of DJ Ro)

At first, Jackson didn’t want anyone to visit him in the hospital. Ever the upbeat entertainer, “he didn’t want people to see him like that,” Ro said. Jackson’s brother and sister-in-law eventually convinced him that social visits would do him good, and from then on his daily visitor quota at the hospital was full, as friends and colleagues came to say goodbye. Ro would play music on his phone for Jackson as he requested favorite songs, such as Rebirth Brass Band’s version of “Lord, Lord, Lord, You Sure Been Good to Me.”

After his death, an outpouring of condolences flowed both locally and from WWOZ’s far-flung listener base. Informal neighborhood second lines were held in his honor for days afterward. The funeral was filled to capacity, and “the whole neutral ground, under the interstate by the funeral home, was full, like a second line Sunday,” Ro said. “When we walked out there, as pallbearers, it was an unforgettable moment, because there were so many people who came out to show love to Action. It showed you how impactful he was to the community. He would have eaten that up.”

Funerals may be for the living more than the dead, but Ro believes that Jackson got to appreciate the extent of his influence before he left this world. His show lives on: community journalist India Sever, who grew up in the second line tradition and has been a hub of information about the scene for years, has taken over as host of Takin’ It to the Streets. Jackson's faith in the power of music and storytelling to reach people fueled his work every time he spun a record, interviewed a community member, or sent a shout-out.

“That’s where the true talent come in, how you can intertwine a life message from the last track or the track that’s about to play; you segue into it,” Ro said. “It do something deep in a person emotionally. That’s the whole point of the DJ-MC-entertainer aspect: when we go to work, we’re spreading joy to the people, and he was good at that.”

Pallbearers emerge from Professional Funeral Services on North Claiborne Avenue carrying Jackson’s casket on August 19, 2021 (clockwise from front left: George Dorsey, Melvin McKenzie Sr., Roland “DJ Ro” Watson, Edward Parker, Michael Gillespie, and Melvin McKenzie Jr). The service was filled to capacity, and a large crowd awaited outside to honor the beloved DJ’s homegoing. (Photograph by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee, courtesy of the artist)