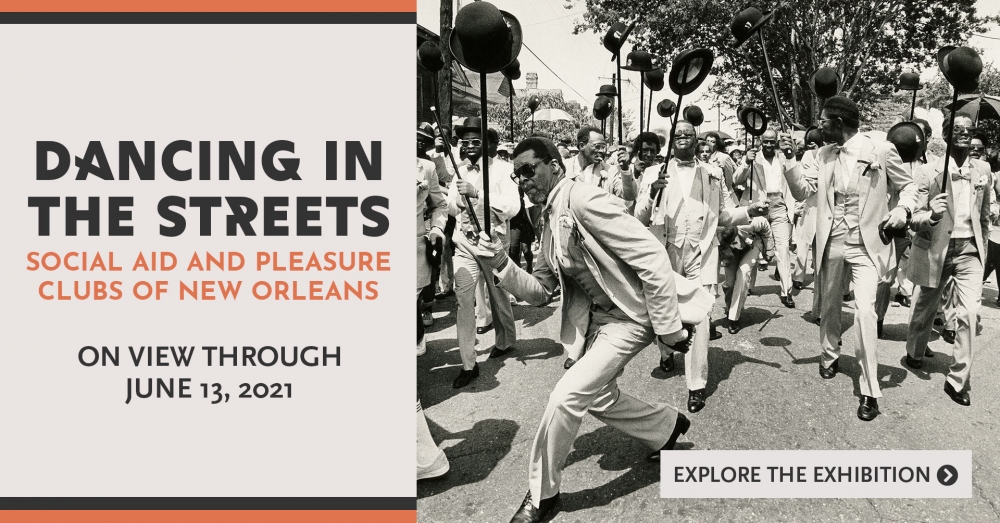

A New Orleans social aid and pleasure club parade offers an array of challenges to photographers attempting to capture the spirit of the procession. The photo subjects are in constant motion, animated by rumbling brass band rhythms. Smoke from food-vendor grills drifts through the air. Crowds of onlookers and second liners flow with the club members through the neighborhood, often cordoned off from the stars of the show—the club members—by associates carrying lengths of rope down both sides of the street.

“Street photography is a sport,” said Bruce Sunpie Barnes, photographer, park ranger, musician, Neighborhood Story Project photo editor, and member of the Black Men of Labor, a social aid and pleasure club in New Orleans. “You should look at it like that. It’s like a sporting event, but it helps to know the subject matter.

“Street photography is a sport,” said Bruce Sunpie Barnes, photographer, park ranger, musician, Neighborhood Story Project photo editor, and member of the Black Men of Labor, a social aid and pleasure club in New Orleans. “You should look at it like that. It’s like a sporting event, but it helps to know the subject matter.

“Often people don’t have a relationship with the actual subjects in their photographs. A lot of those photographers who’ve been shooting second lines for a long time have astutely developed those relationships.”

Access to capture intimate action portraits is earned over beers in favorite club watering holes, in the quieter moments that precede and conclude a parade, and during the kinetic events themselves, where unspoken rules of artistic engagement are observed.

“You need to get to know those people in a deep way,” Barnes said.

Most of the photographers featured in THNOC’s exhibition Dancing in the Streets began shooting second line parades before the onset of the cellphone-camera era and note that the iPhone-ization of the rite may be the biggest change they’ve seen.

“I was fortunate to have come along when I was one of the few photographers shooting second lines,” Eric Waters said. “It was different then. Everybody didn’t have an iPhone, and everybody didn’t have an iPad, and everybody didn’t think they were a photographer.”

View the accompanying slide show to see images from the 12 contemporary photographers who have images displayed in Dancing in the Streets.

Judy Cooper, the photographer whose vision inspired the exhibition and the author of its companion book, first photographed social aid and pleasure clubs at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, but only after introducing herself to the club members in the Fair Grounds’ pre-parade staging area.

When Cooper started photographing street parades in the late 1990s, club routes weren’t regularly published or publicized as they are today. “It took me a couple of years, actually, to chase them down in those days,” she said.

Akasha Rabut, who shoots on film, said she prefers to focus on those in the actual second line—the attendees following the parade—and not necessarily the club members. She has visited many parades without making a single exposure. “You really have to be present and aware and know when the right time is to take a photo,” she said. “Photography can be an extractive thing, exploitative, especially now when so many people have cameras.

“It’s also a vibe. You know when somebody wants you to take their photo, and you know when somebody doesn’t.”

A rule: Get out of the way

Harold Wilson takes to the air at the Black Men of Labor Parade in 2015. (Photograph by Brad Edelman)

“While it’s a sport, it’s just like being at a sporting event,” Barnes said. “You keep your (self) in the stands and off the field and take all the pictures you want.

“Photographing a second line is about social distancing, and it should be adhered to. . . . You’re always going to have some people thinking that making their photograph is more important than the actual event.

“When you get your one good shot, make it count and get out of the way. Those are the more intimate moments anyway. Work to get that shot, and if you carry yourself the right way . . . people putting on that parade see you know how to handle yourself and will give you a beautiful shot.”

Another rule: Share

Sylvester Francis captures video footage in front of the Backstreet Cultural Museum in November 2009. Francis started filming the parades after someone tried to sell him a picture of himself parading, and he was largely responsible for creating today’s photography etiquette. (Photograph by Jeffrey David Ehrenreich, courtesy of the Neighborhood Story Project)

Sylvester Francis captures video footage in front of the Backstreet Cultural Museum in November 2009. Francis started filming the parades after someone tried to sell him a picture of himself parading, and he was largely responsible for creating today’s photography etiquette. (Photograph by Jeffrey David Ehrenreich, courtesy of the Neighborhood Story Project)

A display case in Dancing in the Streets contains cameras once used by Sylvester Francis to document second line parades and Mardi Gras (or Black Masking) Indians. Two of the cameras are instant-printing Polaroid devices.

“Somebody tried to sell him a photo of himself parading,” said Barnes, who as president of the board of the Backstreet Cultural Museum contributed to the formation of Dancing in the Streets. “He decided to get his own camera and created the etiquette of making photos to give them away as relationship building. He was a trendsetter.”

When he photographs a second line, Pableaux Johnson carries packets of prints from each club’s previous parade in his camera bag. “I pack them up and give them to the clubs or give them to the individual members,” Johnson said. “It’s not a transaction. It’s part of the community service. ‘Here. You were absolutely fantastic.’

“By and large, people are usually remarkably gracious. A lot of people don’t know you took their picture.”

Charles Muir Lovell also gives prints to club members. “I’ve also given clubs digital copies,” he said. “If I sell photographs, which unfortunately I don’t sell that many, I donate 10 percent of the proceeds to the clubs.”

Johnson added that the photographers who regularly attend second lines will comb through their archives for representative prints when a club member dies, so that club colleagues and family have a record of that person’s street style.

“You’re basically documenting an informal celebratory culture,” Johnson said. “We go and we shoot funerals and it’s not a voyeuristic thing. You’re doing what you do within the context of the community.”

Another: Enjoy the party, respect the work

Iesha Armstrong parades with the Divine Ladies in 2007. (Photograph by Eric Waters)

“The clubs’ organizational skills are not seen clearly, or respected,” Barnes said. “It’s miraculous you have clubs parading year after year. The main organizers give in blood, I promise you, to make that happen. By the time you get to the parade itself, it’s a release.”

By Barnes’s accounting, the organizational tasks include coordinated attire (“shirts, handkerchiefs, pants, hats, streamers—all that stuff has to match”), obtaining a parade permit, hiring a brass band, and various forms of fundraising to pay for it all. “It all has to come from somewhere and be paid for and be affordable to club members,” he said. “Longstanding organizations know there’s some tremendous community networking going on in there.”

The “third line” of photographers who document the parades are also worthy of respect, Barnes said.

"You have some of the best photographers the city has to offer out there doing their thing, capturing something beautiful,” he added. “They’re spending a lot of money and time, I guarantee. If you ever get back the money you put into all the equipment you bought, it would be a dream come true.”

Last rule: The golden one

The Popular Ladies are pictured at Jazz Fest in 2009. (Photo by Judy Cooper)

Black parading culture is as much a part of New Orleans’s global image as (insert two marketing clichés of your choice here). A photo of a Mardi Gras Indian is the background image greeting visitors to the city’s official website. A fantasy second line silhouette is drawn into the Jazz Fest logo.

Celebrants of those cultures are understandably wary of commodification. An incident with a photographer at her father’s funeral launched Cherice Harrison-Nelson, cofounder of the Mardi Gras Indians Hall of Fame, big queen of the Guardians of the Flame Mardi Gras Indians, and daughter to the late Donald Harrison Sr. (big chief of the Guardians of the Flame), on a years-long mission to protect New Orleans’s Indians and second liners from commercial exploitation, which she describes as “stealing peoples’ intellectual and artistic expression for financial gain—stealing without them in the conversation,” she said. “Of course, we know the copyright laws protect the photographer in public. There’s no reason why, even though that is the situation, that a person can’t decide to do the right thing.”

For when they don’t, there’s Ashlye Keaton of the Ella Project, a New Orleans nonprofit that provides legal and business services to artists, musicians, and culture bearers. Keaton has established that Mardi Gras Indian suits can be copyrighted as sculpture, a pathway to potential compensation when photographs of the suits are sold.

Keaton said the photographers represented in Dancing in the Streets have a collective reputation for playing fair with the subjects of their images.

“Just follow the Golden Rule, right?” she said. “People come to me for legal advice, and I sound like such a homeroom mother about it.

“These photographers are really good about not just the Golden Rule, but also going the extra mile when using the work, contacting folks ahead of time, and making sure they like the picture.”

Altar call

Gerald Platenburg dances at the Nine Times parade in 2019. (Photo by MJ Mastrogiovanni)

Several of the second line photographers interviewed for this story spoke of their work documenting the parading culture as a kind of spiritual calling.

“I try to be totally respectful,” Lovell said. “To me, it’s a religious procession and it’s very spiritual. Some people know me, and I can get a good expression. I’m not necessarily trying to get a smile, per se. Some people are smiling and are joyous, but there’s all kinds of behavior. I really spend a lot of time in editing to make sure that I’m presenting paraders in the best light.”

Added Johnson: “It’s a mixture of the everyday and at the same time it’s spiritual. So much is longitudinal community involvement. You show up every week; it’s like going to services.”

Johnson recalled a conversation with an “amazingly sweet . . . doyenne of the scene” where the subject of his photography came up.

“‘This is kind of like church,’” he said to her. “‘Actually, it’s better than church.’ She gave me a look. I said, ‘Maybe I take that back.’”

Explore modern second line photography at THNOC’s exhibition Dancing in the Streets.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.