Sally Miller’s story starts far from New Orleans, in early 19th-century Europe. The Napoleonic Wars (1803–15) had devastated vast swaths of the continent, and economic crisis had thrown the population into poverty and scarcity. Additionally, a volcanic winter caused by the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora led to massive crop failures and famine in Northern Europe. In Württemberg, a region on the present-day border between northeastern France and southwestern Germany, 16,000 people fled in search of work and food in 1817 alone.

Among them were the Müllers. Though their hometown of Langensoultzbach is now part of France, the Müllers, like most of their neighbors, were German. Daniel Müller, a shoemaker, paid full passage for himself, his wife, and their children to the United States, where they planned to join the German community in the farm country west of Philadelphia. But a Job-like string of bad luck meant the Müllers never arrived in Pennsylvania.

The Müllers first went to Amsterdam, where they boarded a ship set to carry them to Philadelphia, but the brokers to whom they’d paid their life’s savings had no intention of sailing. The family and hundreds of others waited to set sail for four months. Eventually the Dutch government paid for their passage to the United States on the Juffer Johanna. But that ship was not headed to Pennsylvania; it sailed for New Orleans.

A close-up of a map of the Louisiana Territory from an 1814 German-language travelogue. (THNOC, 1978.87)

The trip was not easy. Of the approximately nine hundred Germans in the Müllers’ group, only three hundred lived to see North America, the others killed by sickness and malnutrition. Daniel Müller’s wife Dorothea and their infant son, who had been born while the family waited to depart from Amsterdam, died and were buried at sea. Upon arrival, the bad luck continued. Though their passage was paid for by the Dutch government, the Juffer Johanna’s captain demanded additional payment. Some of the passengers, including Daniel and his surviving children—Jacob, Dorothea, and four-year-old Salomé, called Sally—were sold into indentured servitude. Almost as soon as they landed in the United States, the Müllers found themselves headed to Acadiana as agricultural laborers.

On the journey from New Orleans, Daniel Müller’s bad luck ended; he died. His son Jacob also perished, likely after falling overboard and drowning. Orphans in a strange new country, Sally and her sister made the rest of the journey alone. Relatives and friends searched for them, but it seemed like the young girls had disappeared.

A lost girl reappears

A quarter century after the family’s tragic trip, Salomé Müller resurfaced at a café on the riverfront in New Orleans, where she was recognized by a German woman who had known her extended family. Mrs. Karl Rouff was surprised to see Salomé Müller, not only because the German community had long given up hope of learning what happened to the Müller children, but because Salomé was no longer indentured. She was enslaved, the property of New Orleanian Louis Belmonti.

The little German orphan girl had come back—but now she was Black.

The court case

Sally used the surname Miller in her original court case. Having not yet learned to write, she signed the official paperwork with an X. (Detail from Strange True Stories of Louisiana by George Washington Cable, THNOC, PS1244 .S87 1888)

How could a white orphan indentured near what is now Lafayette in 1818 have, by 1843, become an enslaved house servant in New Orleans? According to Sally's legal team, prominent businessman John Fitz Miller had purchased the Müller family’s indentures and, upon Daniel Müller’s death, taken advantage of the opportunity to claim Sally as chattel. (Sally used the surname Miller in the court case.) After holding her as an enslaved house servant for more than a decade, he sold her and the children she’d had to Louis Belmonti.

The Germans of New Orleans, a tight-knit, well-established community, rallied around Sally. German immigrants first arrived in Louisiana in the early 18th century. Some early arrivals intermarried with French Creoles, but most remained in the ethnic German enclave. They established their own churches—Catholic and Protestant—and a German-language newspaper. They counted prominent landowners, merchants, and lawyers in their ranks. One such man was Bremen-born Christian Roselius, who traveled to Louisiana as an indentured servant shortly after the Müllers. After working off his debt, Roselius became a printer and studied law. He had just completed a two-year term as Louisiana’s attorney general when he agreed to represent Sally in a suit for her freedom. The German community vocally championed her efforts.

Sally lost her original suit but, with the German community’s continued support, she appealed the decision all the way to the Louisiana Supreme Court, where she won her freedom in 1845. When her former master John Fitz Miller sued her for fraud, arguing that Sally’s suit made his family “objects of scorn and reproach to the community,” the court sided with her again.

Sally learned to write during the trial. In later court paperwork, she signed her own name and used the surname Müller. (Detail from Strange True Stories of Louisiana by George Washington Cable, THNOC, PS1244 .S87 1888)

Black and white, but not cut and dried

While the details of her history of enslavement were debated at trial, Sally’s race was the linchpin of the case. As the court wrote, “The first enquiry which engages our attention is, what is the color of the plaintiff?”

The answer to this question was of supreme importance because of the 1810 court case Adelle v. Beauregard, which established that under Louisiana law, a person of color was presumed free. Contemporary audiences might assume that such a law applied to any nonwhite person, but in 19th-century Louisiana, “person of color” had a more limited meaning: it was reserved for people who “may have descended from Indians on both sides, from a white parent, or mulatto parents in possession of their freedom.” That is, a person of color wasn't fully white, but they weren't fully Black either.

Therefore, at issue in Sally’s case was “the record of her complexion”—the degree to which this woman of purportedly unknown parentage appeared to be white.

Though her complexion is fair, the Creole woman in this ca. 1840 portrait would not have been considered white. Instead, she was likely a person of color. (THNOC, 2010.0306)

The case reflected the racism underpinning 19th-century society: the belief that slavery was the natural order of the world, and that Black people—and they alone—belonged in bondage. In her original suit, Sally’s lawyers employed racial and gendered tropes to support their case. They argued, for example, that Sally could not be even 1/16 Black because “the Quartronne is idle, reckless and extravagant, this woman is industrious, careful and prudent.” Though physical inspection was not uncommon in courtrooms of the time, Sally’s lawyers refused to allow her body to be examined. Public poking and prodding was fine for Black people, they said, but not for a white woman. Sally’s support from so many German Louisianians was further evidence not only of the truth of her claim, but of her whiteness. In her successful Supreme Court case, her lawyer used the white public’s support of Sally to “show that she must be white.” An “idle, reckless” Black woman wouldn’t have been able to pull the wool over so many white eyes.

The arguments and the decision highlight how much racial designation depended on contexts that had little to do with ancestry. One witness for the defense stated that he “always thought she had something resembling the colored race in her features,” but went on to admit that he may only have thought so because he saw Sally with nonwhite people. The judge’s explanation of a particular weakness of the defense’s case also speaks to how an individual's race was affected by their connection to the race of the people associated with them. As the decision explains, the defense failed to show evidence that Sally was “the daughter of a particular colored person, who was in fact a slave.”

“White slavery”

Sally’s case stood out for being legislated all the way to Louisiana’s highest court, but light-skinned enslaved people were neither new nor rare.

As far back as the Spanish colonial era, when sumptuary laws demanded all nonwhite women wear head coverings, or tignons, people sought visual clues outside of skin color to clarify a person’s race. For the woman on the right, described as a “mulatre,” and the woman on the left, who is dressed in expensive clothing, the headwraps may have helped mark them as Black. (THNOC 2016.0289, 1984.2.1, 2005.0347)

“White slavery” was a hot-button issue in the years after Sally gained her freedom. The term entered abolitionist discourse in 1847, when the US senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts used the phrase to describe the enslavement of Christians by Muslim traders in North Africa. Abolitionists like Sumner didn’t simply liken “white slavery” to the racialized slavery of the US South. They argued that Black slavery led to white slavery—that Black enslavement led to the sexual abuse thought to be common in the Barbary States of North Africa and in the Ottoman Empire, where they imagined scores of white European women held in wealthy Muslim slave traders’ harems.

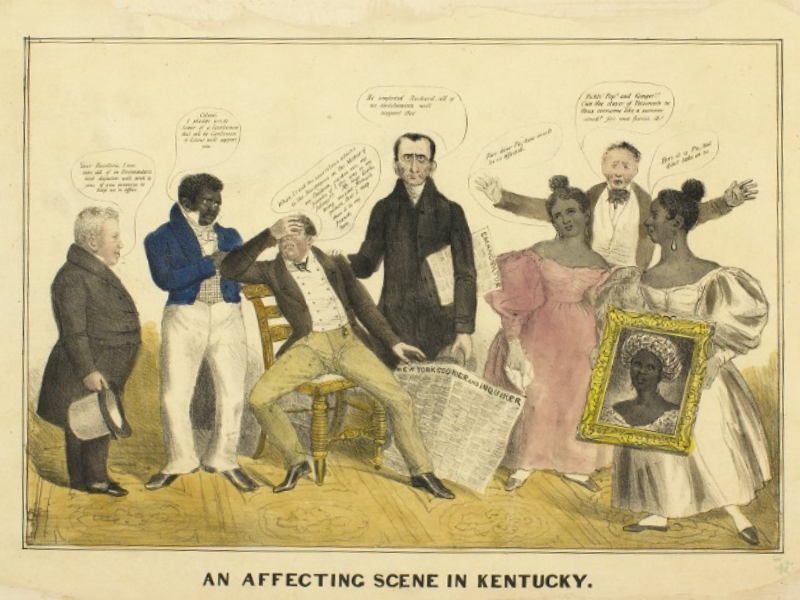

When Richard Mentor Johnson ran for vice president under Martin Van Buren in 1836, political cartoons mocked his long-term relationship with an enslaved woman named Julia Chinn and with their mixed-race children. (Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia)

The connection between chattel slavery and sexual immorality had long been a concern in the US imagination. Thomas Jefferson’s relationship with the enslaved Sally Hemings was fodder for his political opponents and the inspiration for William Wells Brown’s 1853 book Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States. Widely considered the first novel published by an African-American, Clotel includes a character based on Sally Miller—a “perfectly white” enslaved woman named “Salome,” who recounts her life story in a chapter called “A Free Woman Reduced to Slavery.” While the details of the character’s childhood and enslavement differ from the the real Sally’s, her core story is the same:

I will tell you why I sometimes weep. I was born in Germany, on the banks of the Rhine. Ten years ago my father came to this country, bringing with him my mother and myself. He was poor, and I, wishing to assist all I could, obtained a situation as nurse to a lady in this city. My father got employment as a labourer on the wharf, among the steamboats; but he was soon taken ill with the yellow fever, and died. My mother then got a situation for herself, while I remained with my first employer. When the hot season came on, my master, with his wife, left New Orleans until the hot season was over, and took me with them. They stopped at a town on the banks of the Mississippi river, and said they should remain there some weeks. One day they went out for a ride, and they had not been gone more than half an hour, when two men came into the room and told me that they had bought me, and that I was their slave. I was bound and taken to prison, and that night put on a steamboat and taken up the Yazoo river, and set to work on a farm. I was forced to take up with a negro, and by him had three children. A year since my master's daughter was married, and I was given to her. She came with her husband to this city, and I have ever since been hired out.

William and Ellen Craft’s Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; or, The Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery, published in England in 1860, references Sally’s story in their accounting of fellow fugitives from slavery in the United States. The Louisiana courtroom drama had become fodder for the international abolitionist movement.

Abolitionists who wanted to highlight sexual relationships across the color line found many candidates in New Orleans, where French and Spanish colonization had contributed to a large population of enslaved people of mixed European, African, and Indigenous descent. Images of enslaved or recently freed light-skinned children were used in campaigns to elicit sympathy from Northerners who felt distant from slavery. The message resonated. In an 1853 letter to William Lloyd Garrison, fellow abolitionist Parker Pillsbury wrote that “white skin is no security whatsoever. I should no more dare to send white children out to play alone, especially at night . . . than I should dare to send them into a forest of tigers and hyenas.” If these white-appearing children could be enslaved, the postcards seemed to say, so could yours. Some of the white public's sympathy and support for Sally also reflected racist ideas about white women's sexual purity and Black men’s hypersexuality. Sally had four children while she was enslaved, presumably fathered by one or more enslaved Black men. To white people following her story, the fact that a white woman's enslavement could lead to her having sexual contact with a Black man was abhorrent.

Sally was already free by the time postcards of “white” slave children circulated. Even after Sally was declared free, her children remained in bondage—but they, along with all enslaved people, would finally gain freedom with the defeat of the Confederacy in the Civil War.

Postcards with fair-skinned Black children who had been enslaved were meant to garner support and sympathy from white Northerners. They were often dressed like the children of respectable white families and posed with patriotic symbols. (THNOC, 1980.25, 1992.68.3)

After the trial

Sally disappears from the historical record after the trial. There is evidence that she was living in California in the late 1850s; there is no known record of her death or burial place. But the fallout from her court case continued.

Slaveholders and slavery supporters railed against the court’s decision to side with an enslaved woman against her masters. Louisiana planters feared that the large population of mixed-race enslaved people might be inspired to follow Sally’s example. In 1846, a year after Miller v. Belmonti, the Louisiana State Constitutional Convention abolished the Supreme Court. This may have been retribution against the jurists who granted Sally her freedom. None of them were reappointed as members of the new court, established one day later.

Nearly a half century later, Sally’s legacy lived on. George Washington Cable, a white New Orleanian writer and friend of Mark Twain, who is best remembered for writing about Creole life, recounted Sally’s story in his 1890 collection Strange True Stories of Louisiana.But with the end of chattel slavery in the US, the decision in Sally’s case became irrelevant. The social systems that defined Louisiana before the Civil War faded and demographics shifted. The white Creole population was overtaken by white Anglo Americans. The German community largely assimilated into white American society. With the hardening of the color line after the Civil War, the class distinctions afforded free people of color and Black Creoles who would have been most greatly affected by Sally’s case disappeared. In the new racial order, they were simply Black. This redefinition was effectively codified by the US Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, which upheld binary segregation in Louisiana.

In short, Sally’s case no longer mattered, and the groups who had cared about it faded away. With the exception of John Bailey's recounting of the dramatic proceedings in his 2003 book The Lost German Slave Girl and intermittent calls for the story to be made into a movie in internet forums, interest has largely faded. Even two centuries later, no one knows if the Sally whose case made it to the Louisiana Supreme Court was really the little German girl named Salomé Müller—and most people don't know she existed at all.