In 1866, at a time when horse racing was arguably the most popular sport in America, the New Orleans Times hailed Abe Hawkins as “probably the best rider on the continent.” Once enslaved on a Louisiana plantation, Hawkins, in just a few years, achieved fame and fortune, and changed the sport forever.

From the moment enslaved Africans arrived in the Western Hemisphere, white colonists relied upon them to manage stables and provide veterinary care to horses. Black trainers, grooms, and riders made essential contributions to the Revolutionary War effort. In the 19th century, Southern planters used the sport of horse racing to flaunt their status, creating a particularly warped social dynamic. Enslaved horsemen had autonomy others didn’t, but Katherine C. Mooney explained in her book Race Horse Men that “they were also subject to more subtle pressures…the knowledge of their own difference, the fear of their privilege’s fragility, and the tension of constantly calculating self-interest that often divided them sharply from loved ones and colleagues.”

Hawkins was enslaved on Duncan Kenner's Ashland plantation until Union troops raided the home in 1862. (THNOC, 1974.25.26.226)

Little is known about Hawkins’s early life, but his reputation as a jockey led sugar planter Duncan Kenner to purchase him from a Natchez man in 1854 for $2,350, a considerable sum of money. Kenner was a “turfman”—a wealthy man invested in horse racing—and had a racetrack built on his Ashland Plantation. Hawkins quickly made headlines in April 1854 when, at the Metairie Jockey Club, he rode the horse Lecomte—the namesake for the Lecomte Stakes, held in January at the Fair Grounds—to a world-record-setting victory over Lexington, a legendary Kentucky thoroughbred. He became the rare enslaved jockey to be mentioned by name in race reports—though usually simply as “Abe” or “Old Abe.”

A lithograph shows the legendary racehorse Lexington who suffered defeat to Lecomte, jockeyed by Hawkins at a world-record-setting pace in 1854. (THNOC, 1974.25.2.147)

In August 1862 Union troops raided Ashland. Kenner escaped on horseback, leaving behind his wife, children, and slaves. Amid the chaos, Hawkins, too, slipped away. His name appears again in St. Louis race reports in 1864. As a free man, Hawkins became a bona fide superstar, amassing a small fortune winning races throughout the North, including the 1866 Travers Stakes. In another legendary race, he beat the Irish star Gilbert Watson Patrick in front of a crowd of 25,000 in New York City. Hawkins drew the biggest crowds, rode the best horses, and his unique talent precipitated a paradigm shift among gamblers, who started paying more attention to riders than horses when placing bets.

An 1863 lithograph from Harper's Weekly shows the sale of confiscated horses by Union soldiers. Duncan Kenner's horses were among the animals sold. (THNOC, bequest of Boyd Cruise and Harold Schilke, 1989.79.16.12)

Hawkins developed tuberculosis—common among jockeys, who practiced extreme dieting—and his health deteriorated. He returned to Ashland at the end of his life, and died there in 1867.

A popular story shared among turfmen for years was that when Hawkins learned about Kenner’s wartime financial losses, he offered to send him his race winnings. Historians dispute its veracity, but turfmen perpetuated it because it reinforced myths about a benevolent antebellum racial hierarchy. Black jockeys—such as Oliver Lewis, who won the first Kentucky Derby in 1875—dominated racetracks until the Jim Crow era, when white jockeys and clubs increasingly used discriminatory hiring practices, intimidation, and violence to force them out of the sport.

A version of this article originally appeared in the Historically Speaking column of the New Orleans Advocate.

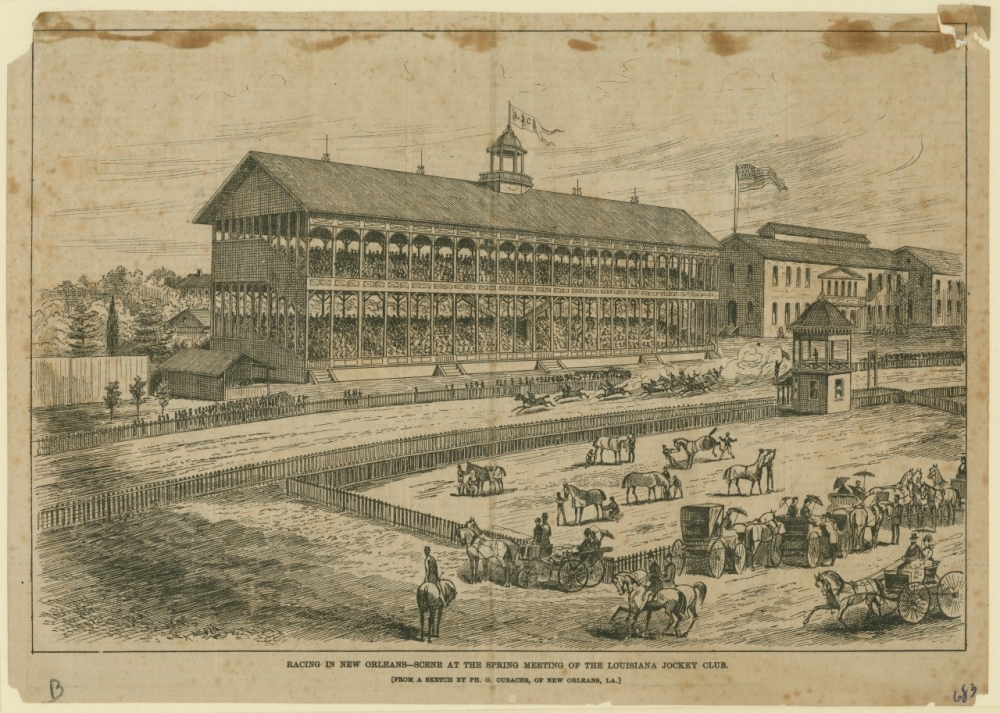

Cover image: Racing in New Orleans—Scene at the Spring Meeting of the Louisiana Jockey Club; April 24, 1874; illustration by Philip G. Cusachs, delineator; THNOC, 1974.25.2.208

Cover image: Racing in New Orleans—Scene at the Spring Meeting of the Louisiana Jockey Club; April 24, 1874; illustration by Philip G. Cusachs, delineator; THNOC, 1974.25.2.208