Before its ruins provided scenery for portions of Beyoncé’s visual album “Lemonade,” HBO’s series “True Detective,” or AMC’s “Into the Badlands,” Fort Macomb was considered a crucial line of defense for New Orleans and the country at large.

Situated along the Chef Menteur Pass, the semicircular masonry structure was built as part of the United States’ “Third System” of coastal defense—the third Congress-initiated effort to fortify America’s coastal borders since independence. British intrusions made during the War of 1812, including those that led to the burning of Washington, DC, and the Battle of New Orleans, inspired the construction of 42 new forts (and renovations to old structures) along the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coasts. In 1816 President James Madison tasked French general and engineer Simon Bernard, who had served under Napoleon, with overseeing the initiative.

A 1968 image by Betsy Swanson shows the moat and sally port at Fort Macomb. (THNOC, gift of John Geiser III, 2009.0045.3)

One of Bernard’s first actions was to survey the Mississippi Delta, including the Chef Menteur Pass, which connects Lake Borgne to Lake Pontchartrain. He created a new design for the site of a small earthwork battery that had been built during the Battle of New Orleans, as well as for a number of other locations in southeastern Louisiana, including Fort Pike along the Rigolets and Fort Jackson along the Mississippi River, near the older Fort St. Philip. Fort Macomb and Fort Pike share in common an unusual curving front wall that created a wide target range for cannons set inside barrel-vaulted casemates.

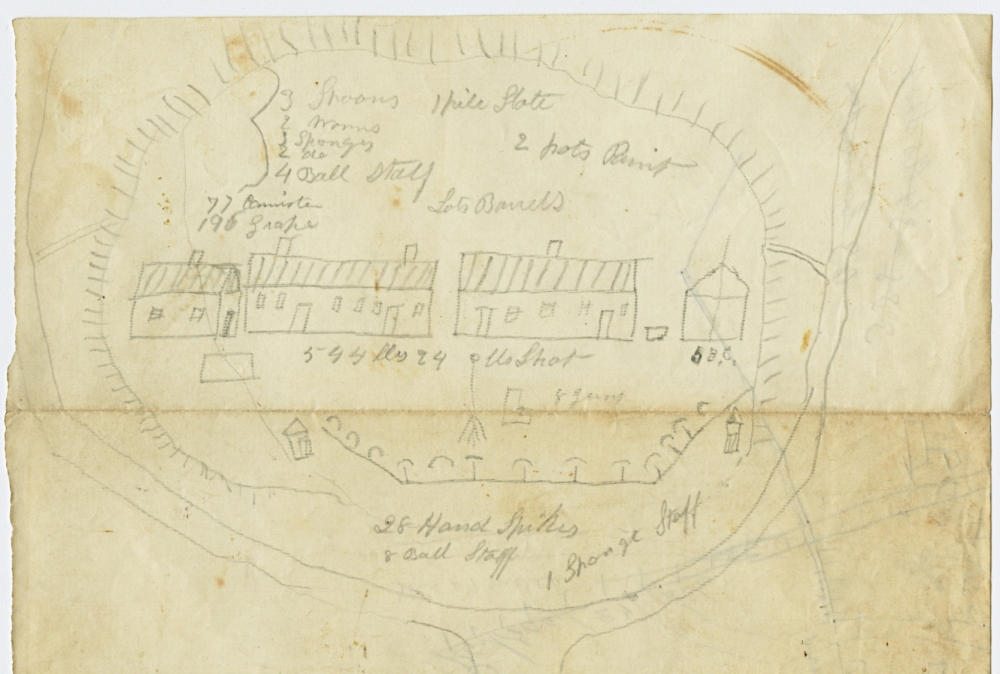

A letter from Lieutenant O.W. Lull to General Benjamin Butler contained this handdrawn map of Fort Macomb, after Union troops occupied it. (THNOC, 99-54-L.2)

Fort Macomb, known as Fort Wood until 1851, was completed at cost of more than $350,000, and was finally garrisoned in 1828. Confederate troops occupied it at the beginning of the Civil War but abandoned the post when the Union captured New Orleans in April 1862. A month later, Union Lt. Col. O. W. Lull took command of the fort, and wrote a letter to Gen. Benjamin Butler that included a list of supplies and a hand-drawn map. The fort’s tenants during the Civil War included the First Louisiana Native Guard, which was among the Union Army’s first all-black units.

A 1967 image by Betsy Swanson shows the interior of Fort Macomb. Though it was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978, it is closed to the public today. (THNOC, gift of Ralph B. Draughon Jr., 2009.0230.1)

The fort never engaged in battle, and suffered a fire to its barracks in 1867 that contributed to its decommissioning and abandonment four years later. By then, improved weaponry had rendered the Third System masonry forts largely obsolete. Hurricanes have battered Fort Macomb over the years, and nearly a century-and-a-half of neglect has left it overrun by nature and susceptible to vandalism. Its vine-tangled ruins have attracted photographers for decades and filmmakers more recently. Though it was named to the National Register of Historic Places four decades ago, in 1978, it is closed to the public today.

A version of this article originally appeared in the New Orleans Advocate's Historically Speaking column, which is a collaboration between the newspaper and The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Cover image: Our Colored Troops at Work—The First Louisiana Native Guards Disembarking at Fort Macombe, Louisiana (detail); February 28, 1863; illustration from Harper’s Weekly (THNOC, 1974.25.9.6)