In 1967 the American counterculture movement exploded onto the mainstream with the Summer of Love, when roughly 85,000 young people convened on San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood in search of a communal utopia. Hippies, flower power, and the movement against the Vietnam War formed a cultural phenomenon that remains an iconic, highly mythologized part of Americana. The dominant narrative of that time situates the counterculture primarily in California, but New Orleans had its own Summer of Love.

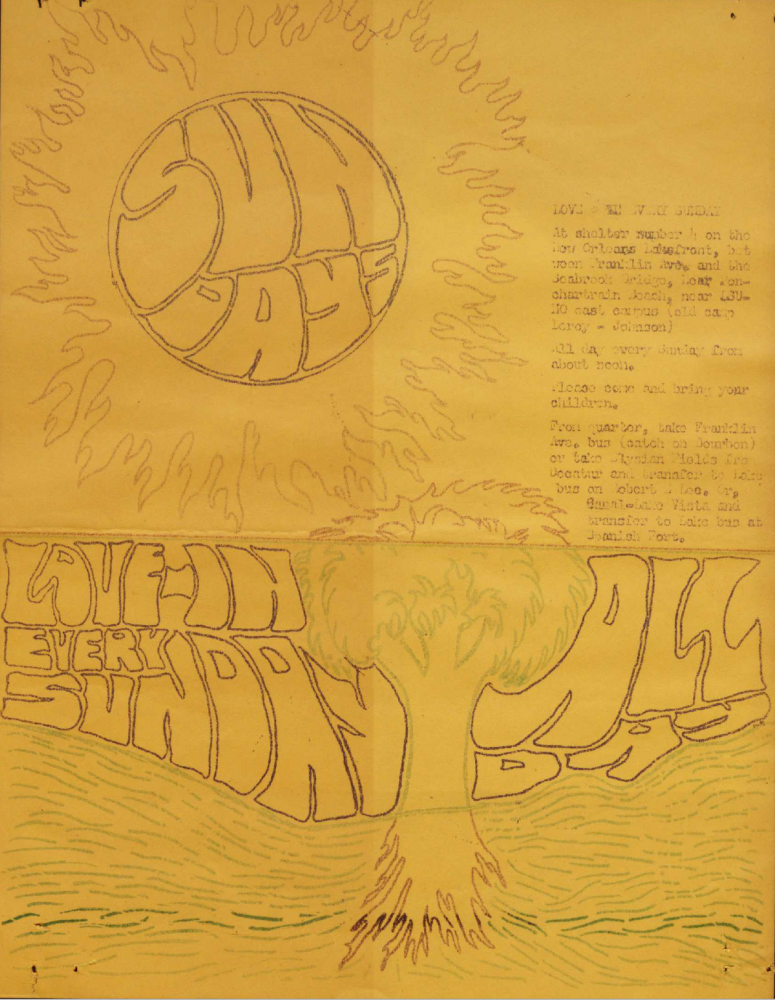

Starting in June 1969, a series of weekly love-ins brought together like-minded folk in celebration of free music and good vibrations. The gatherings were peaceful but not always tolerated by local authorities or conservative civic groups. Booted from one public park to the next, the love-ins migrated across the city over the ensuing months, relying on word of mouth and the city’s alternative press to stay active.

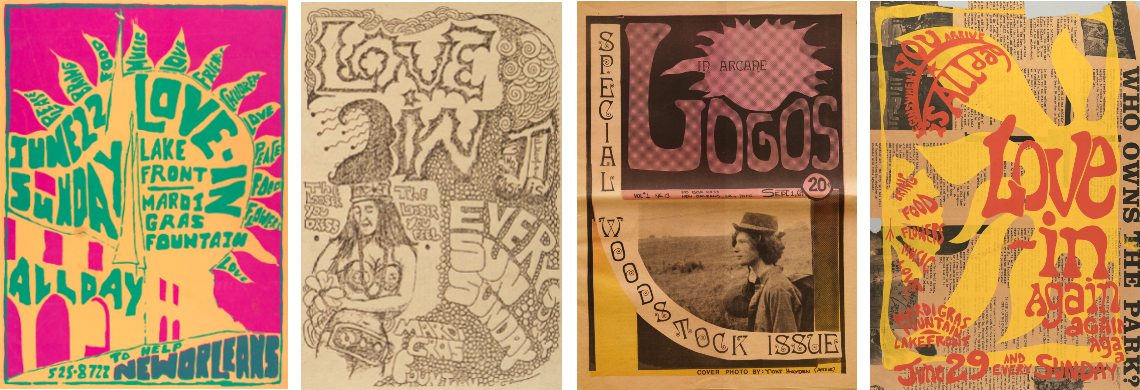

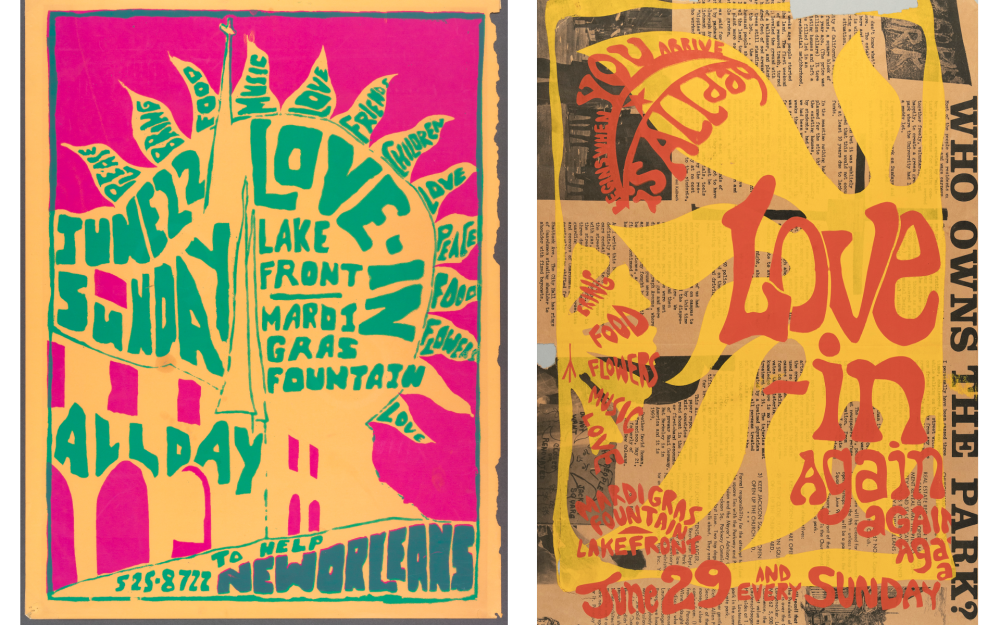

Both of these love-in posters, designed by James DeGraff in June 1969, were provided to The Collection by Dan Gifford, who was a high school student and budding graphic artist at the time with a sideline gig selling underground newspapers. (Left–right: THNOC, 2021.0179.20, .18)

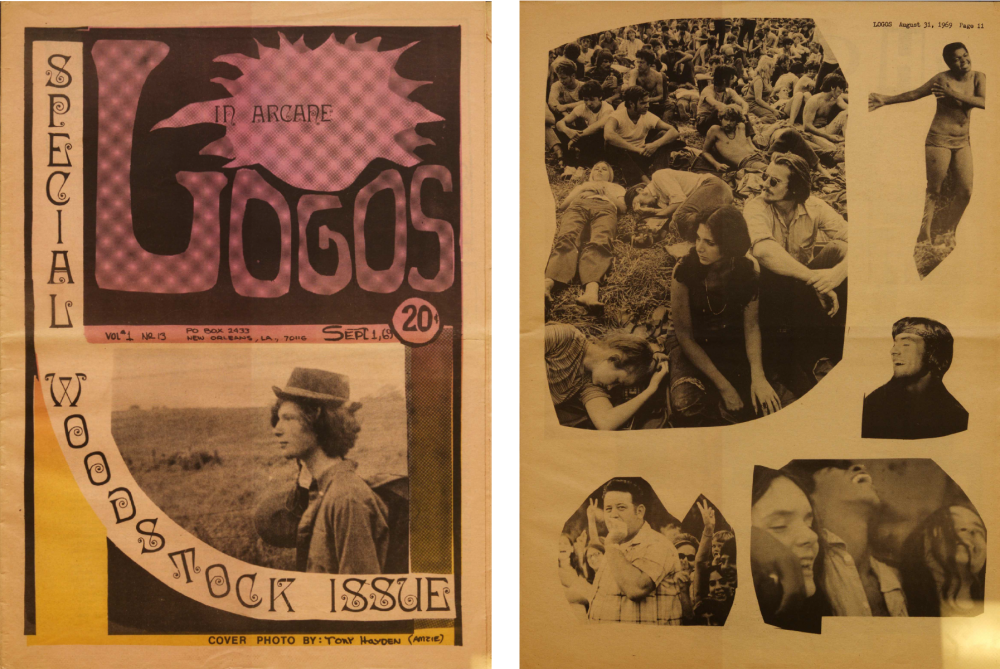

Adding to the momentum of the moment was Woodstock. A contingent from the New Orleans magazine In Arcane Logos made a pilgrimage to the upstate New York music festival and had their minds blown, returning home more certain than ever about the dawning of a new age of love and understanding. Two weeks later, over Labor Day weekend, Louisiana capped off its Summer of Love with a local answer to Woodstock—the New Orleans Pop Festival, featuring headliners Canned Heat, Janis Joplin, the Byrds, and the Grateful Dead.

“Many, many people today are pulling away from the society that produced them,” wrote In Arcane Logos contributor Millie, covering the opening of an ashram in the French Quarter for the August 6, 1969, issue. “I say to you that we are not going to let the children of the future have rings in their noses and be led around.”

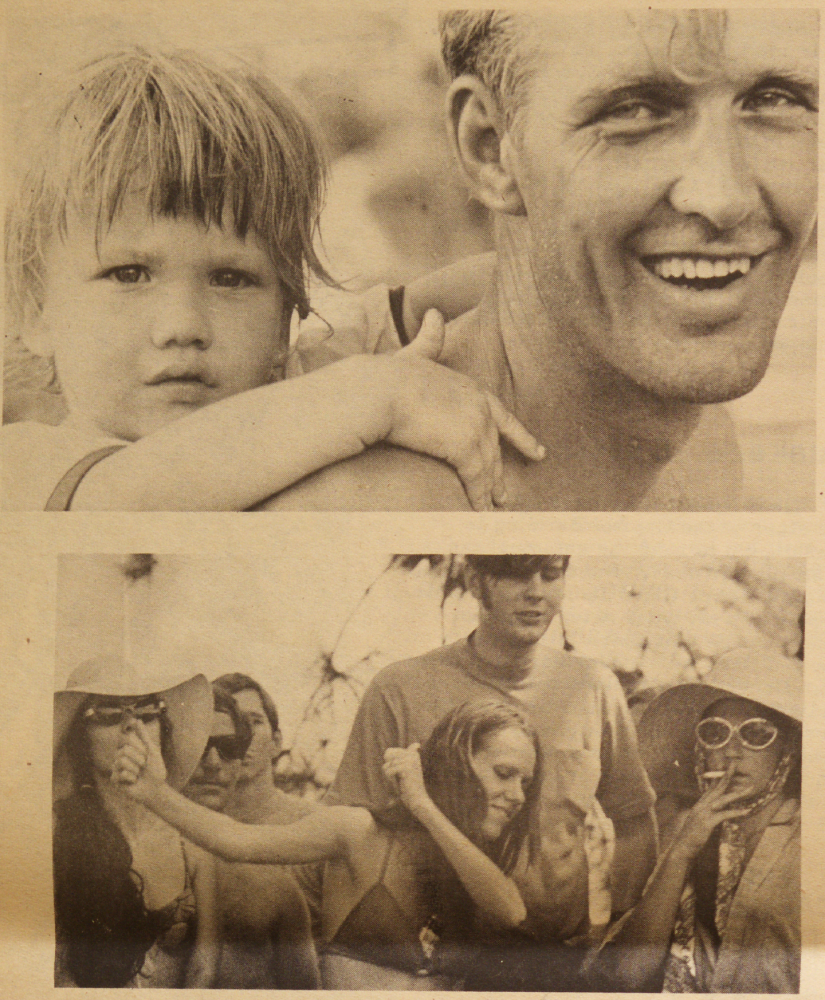

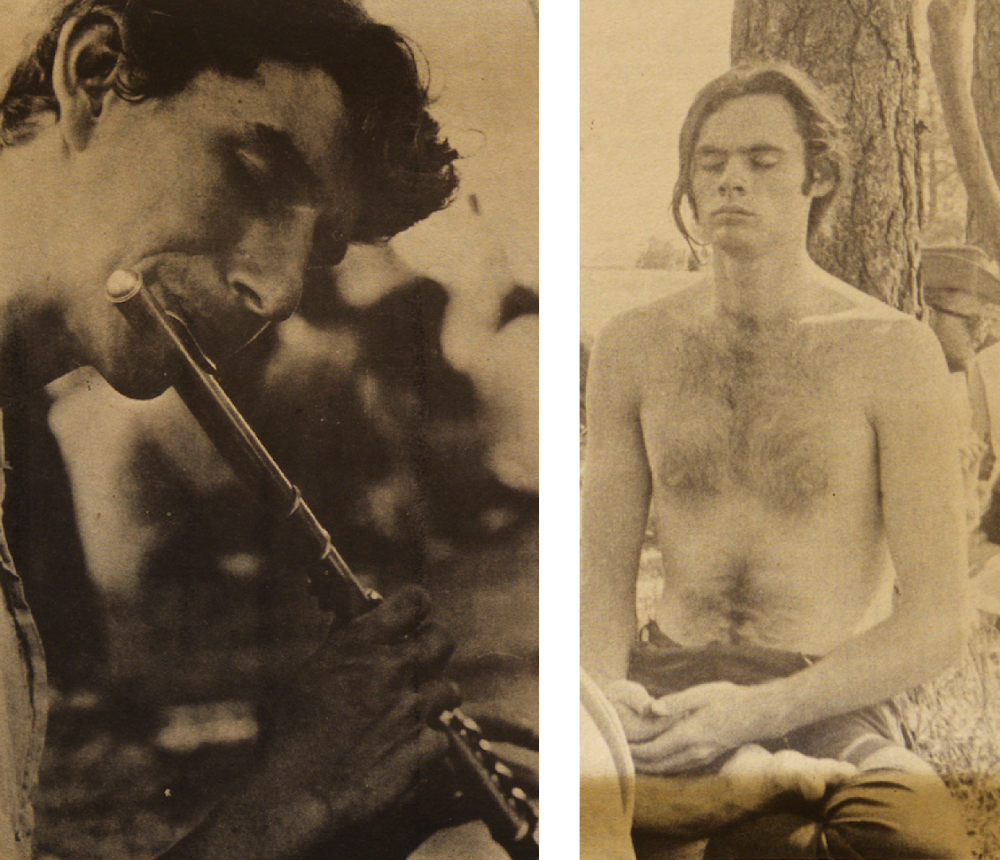

Approximately 400 people showed up to the first love-in, held at Mardi Gras Fountain on Sunday, June 22, 1969. These images, by photographer Tony Hayden, were published two weeks later in the underground magazine In Arcane Logos. (THNOC, AP2. I33)

Letting Love In

The New Orleans love-ins started out as an import from California, instigated by a Los Angeles man named Jim Vance. Described by the States-Item as “bearded, barefoot, and bare-chested,” Vance had already staged love-ins in San Francisco and New York before coming to New Orleans in May 1969 and slipping into the thriving counterculture scene. The French Quarter had long been a bohemia for artists and free-thinkers, going back to William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams in the 1920 and ’30s. The “heads,” or hippies, of the late 1960s built on that foundation, coexisting—if not always gelling—with an existing network of beatniks, jazz devotees, and artists.

According to THNOC’s oral history of artist Amzie Adams, who moved to New Orleans in 1969, “there were hippies everywhere.” In the French Quarter, there were more than a dozen bars, coffeehouses, and shops catering to heads. “You could get beans and rice for a quarter, and rent was $35 a month. It was great.”

Painter and photographer Amzie Adams first arrived in New Orleans in 1969, quickly becoming ensconced in the city’s thriving underground press. Adams gave his oral history to THNOC in 2015. (THNOC, photograph by Keely Merritt, 2015.0486.1)

The French Quarter was also the center of action for New Orleans’s underground press. In addition to In Arcane Logos, periodicals like Balls, the Ungarbled Word and NOLA Express chronicled the political, cultural, commercial, and artistic ideas coming out of the counterculture. The papers championed marijuana legalization, railed against police brutality against Blacks and police harassment of hippies, and featured psychedelic, occasionally pornographic art.

“There was a big divide between the people who were growing their hair long [and the establishment], all across the country,” recalled Jimmy Robinson, a guitar player whose band at the time, Ejaculation, played at the love-ins. (The band name, he said, was a Catholic reference, meaning a short prayer.) “Harassment was really common, especially in the French Quarter, I guess because they had the tourism industry to maintain.”

Jim Vance sought permission from various authorities to stage the first love-in, but “they all said no,” he told the States-Item. Vance and his new New Orleans friends forged ahead, selecting Mardi Gras Fountain on the lakefront as the site and reaching out to bands to play for free. On Sunday, June 22, the love-in went on, gathering an estimated 400 people into a “sea of pulsating humanity” where “beads and bell bottoms shook and swayed” and “beer flowed swifter than the fountain,” the newspaper reported.

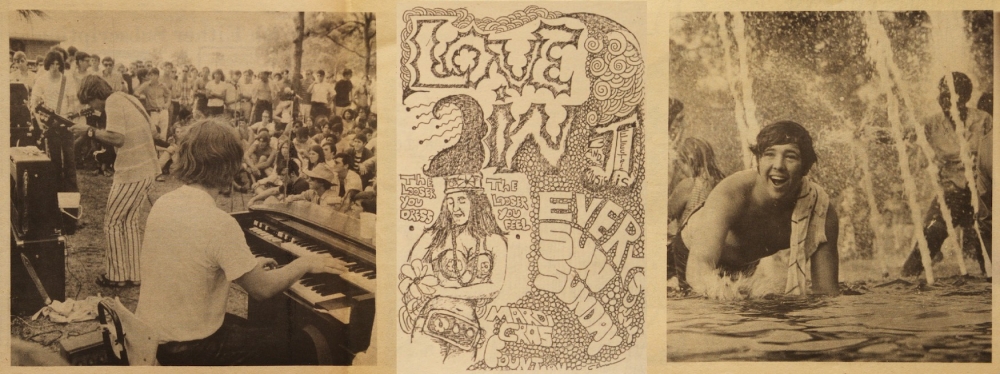

Photographs from the first love-in, taken by Tony Hayden for In Arcane Logos, show a band playing (left) and an attendee cooling off in Mardi Gras Fountain (right). (THNOC, AP2. I33)

Police presence wasn’t a factor until the summer heat prompted some attendees to cool off. “Everybody jumped in the fountain,” Robinson said. Once the cops arrived, officers told the bathers to get out of the fountain but allowed the event to continue. The bands played on (five in all), and New Orleans made its mark on the burgeoning love-in trend, helping to defang the counterculture for those who saw it as a menace. “The cops have the wrong idea about what a ‘love-in’ is,” Vance told the States-Item. “All it is, really, is a great big picnic.”

“It was a trend that was happening all over the country,” Robinson said. “And it was basically a bunch of young hippies wanting to get together, you know, the whole theme of love and antiwar and all that. It was a free concert that anyone could go to.”

Half a Million Strong

Vance left town soon after the inaugural love-in—he claimed the cops had it out for him and were going to try to bust him for drug possession—but the gatherings continued every Sunday. “The hundreds of people who have come out have done their thing, or nothing, and have heard music by the Paper Steamboat, White Clover, Flavor, Impulse Federation, the Louisiana Ball, and Freon,” wrote In Arcane Logos editors in the July 3, 1969, issue, which featured a centerfold photo essay from the love-ins. In the classifieds section, editors included directions to the lakefront via public transportation. “People who like people, or who like watching people, will probably want to go out Sundays.”

Officials’ tolerance for the gatherings, however, soon ran out. The Orleans Parish Levee Board, which managed public spaces along the lakefront, notified love-in organizers that they would no longer be able to use the electrical hookups near the fountain to power the amplified music. So began a migration to different spots around town: “It moved down the lakefront to a shelter close to the Seabrook Bridge,” Robinson said. “After that we moved to Popp Fountain in City Park. We had a lawyer at the time, like a hippie lawyer, and they set up a meeting with City Park, helped us clear the way. City Park allowed us to use their power for a while, but then it got too rowdy, too many people smoking pot and all that. Ultimately, we ended up at Audubon Park, originally at a shelter near the original Monkey Hill, and then to the riverfront, the area they call the Fly today.”

Scenes from the love-ins in June 1969, taken by Tony Hayden (THNOC, AP2. I33)

Robinson was a student at the University of New Orleans at the time, living nearby in Lake Terrace. When the love-ins moved to Audubon Park, playing with his band meant trekking across town to make the gig, but it was worth the hassle. “I’d wake up at 5 a.m. and ride my bike all the way to Audubon Park to stake out the shelter,” he said. “I was dedicated. My introduction to the music scene was this—playing big crowds at these free shows. It was really a shot in the arm for a young kid.” Robinson has since toured the world as a career guitarist, and he cofounded the ensemble the New Orleans Guitar Masters.

As the love-ins made their way around New Orleans in the summer of ’69, word spread about the Woodstock Music and Art Fair, which was to take place over three days in mid-August. The editors of In Arcane Logos had been granted press badges by the festival, and they used ad space to solicit contributions for the 1,300-mile road trip to Bethel, New York.

“We all got in a crazy hippie van, the whole newspaper, nine hippies or something, and all our stuff, riding out to Woodstock,” Adams recalled in his oral history. “We had . . . a big hippie rocket ship and a rumble seat, but we were the press. ‘Come on in.’ We parked right behind the stage, and we watched them build the stage for Woodstock.”

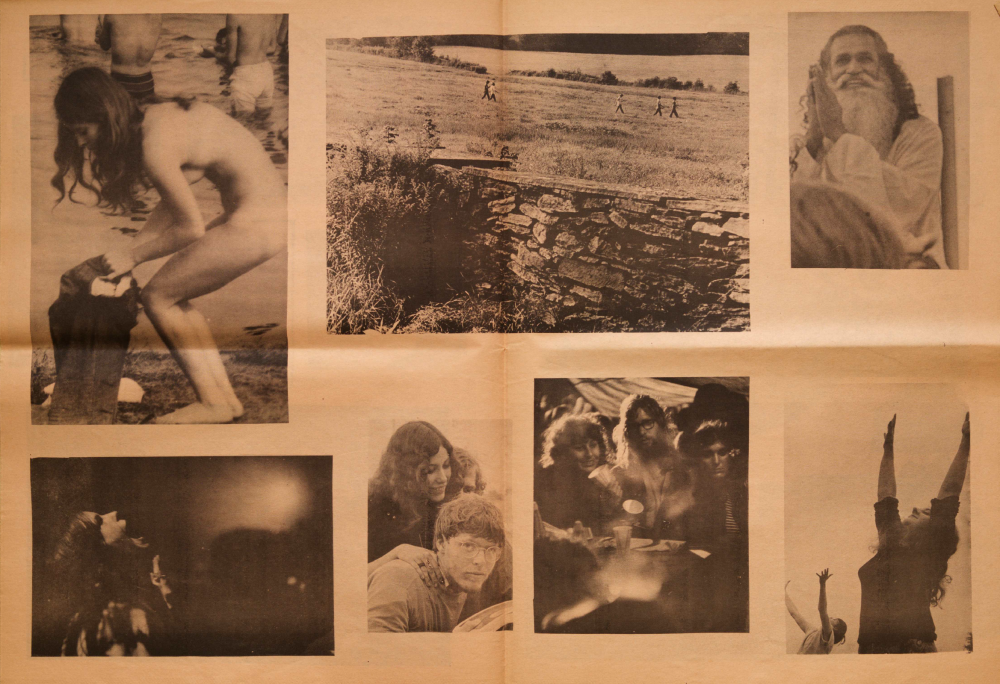

In Arcane Logos photographer Tony Hayden captured these images from Woodstock for the magazine’s Sept. 1, 1969, issue. (THNOC, AP2. I33)

The staff returned to New Orleans so inspired they devoted the entire September 1 issue to the festival. Like many who attended, they saw Woodstock’s lack of violence, police interference, or hardship—aside from some “bum trips”—as proof of the possibility for mankind to live peaceably and equitably. “What it was was two weeks of total communication, where almost half a million people joined in a Oneness whose birth-cry sounded Love,” read a contribution to the Woodstock issue, signed Rankin and Fred.

In an open letter to the New Orleans Police Department, editors wrote of the 400,000-person “city in New York” that existed for those three days, holding it up as an ideal of tolerance: “What happened was beautiful. Both parties [police and attendees], being allowed to see each other as people rather than members of uniformed classifications, were able to open their minds and share themselves. What naturally followed was understanding. What we’re trying to say is that this can work in New Orleans as well.”

Upon returning from Woodstock, In Arcane Logos dedicated its next issue to the festival. (Photographs by Tony Hayden, THNOC, AP2. I33)

From Woodstock to Prairieville

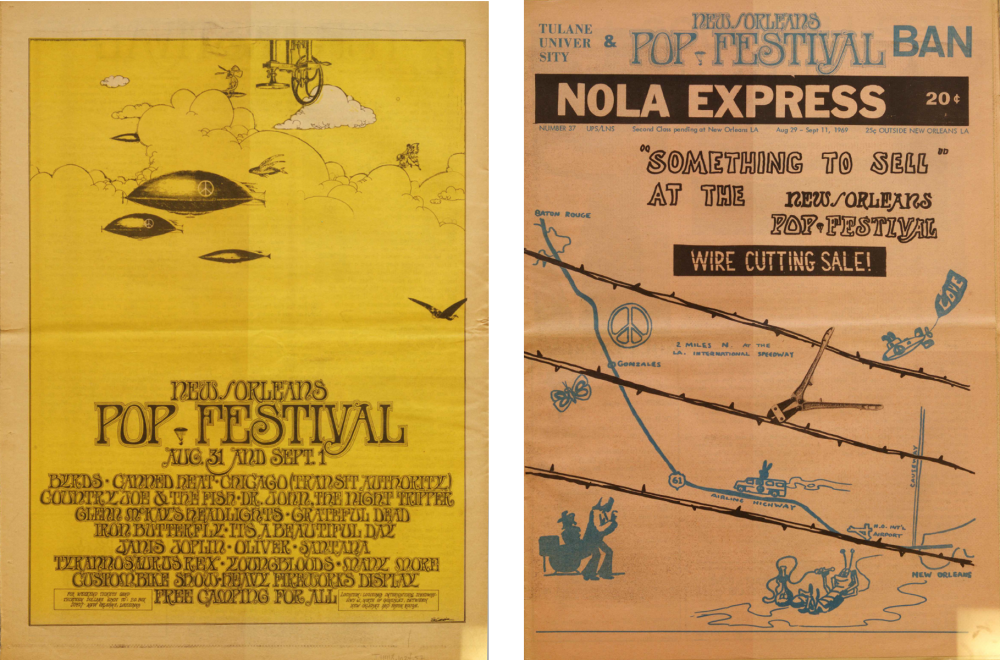

The chance to re-create the magic of Woodstock locally came two weeks later, with the New Orleans Pop Festival. Held over Labor Day weekend at a speedway in Prairieville (one hour west of New Orleans), the festival featured many of the same acts that had played Woodstock—Janis Joplin, Country Joe and the Fish, Canned Heat, Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead—as well as Iron Butterfly, It’s a Beautiful Day, and the Youngbloods.

Even before the festival, critics warned that a Woodstock repeat probably wasn’t in the cards: one intrepid reader of NOLA Express wrote in to declare that the site “ain’t worth a hardy sh**,” as it was on pavement with nowhere to camp and “a dump 100 yards away.” Promoter Steve Kapelow had no intention of losing money on attendance, as Woodstock’s organizers had done by allowing throngs of people to enter for free through a broken fence. Instead, Kapelow’s team installed tall fencing topped with barbed wire. NOLA Express criticized the move, running a cheeky ad for wire cutters with instructions for hopping the fence.

Attendance couldn’t compete with Woodstock’s phenomenal 400,000-plus, but upward of 20,000 people attended the New Orleans Pop Festival over the holiday weekend. According to newspaper reports, in addition to the expected demographic of hippies and freaks, the festival attracted plenty of run-of-the-mill college students, identifiable in their sorority and fraternity shirts.

Dan Gifford, who was in high school at the time, went the first night and didn’t leave until the next day. “The show didn’t end until sunrise the next morning,” he said.

A full-page ad for the New Orleans Pop Festival (left), designed by Stephen St. Germain, ran on the back cover of NOLA Express leading up to the festival. The cover of the August 29 issue (right) skewered the festival’s decision to put up barbed-wire fencing—a marked contrast to the free entry made famous at Woodstock. (Left and right: THNOC, MSS 647 f. 423)

Local businesses near the festival site were anxious leading up to the influx, but the crowds’ good behavior and spending money won them over. “All of us were really terrified at first,” said Edith Webb, owner of Webb’s Grocery. “Everyone in the area had been building up what could happen. They had us believing they’d butcher our cows for barbecue or paint flowers on them.” In addition to the festivalgoers being “perfect customers,” Webb said she’d made two weeks’ earnings in three days.

“These hippies were better behaved than many of our local residents,” one man told the States-Item. “I wouldn’t have believed these people were for real if I hadn’t seen it myself.”

While many locals were pleasantly surprised by the hippies and their fun, the police weren’t interested in turning a blind eye. Thanks to the 116 plainclothes officers in the crowd, each day of the festival brought a fresh batch of drug arrests, 35 in total. The suspects were held in jail on $50,000 bonds. Back in New Orleans on the Saturday of the festival, cops arrested three separate men for selling LSD on the streets of the French Quarter. Police told the Times-Picayune that one young man, an 18-year-old who had traveled from New York specifically for the festival, was selling his wares “as openly as a hot dog vendor.”

The Dead, the Allmans, and the Legacy of the Love-Ins

The New Orleans Pop Festival closed out the city’s unofficial Summer of Love, but the love-ins continued every Sunday throughout the fall and into the winter. “It was huge,” Robinson said. “By the end of the run at the Fly, there’d be 2,000, 3,000 kids out there. It went on until winter, until it got too freezing to do it.”

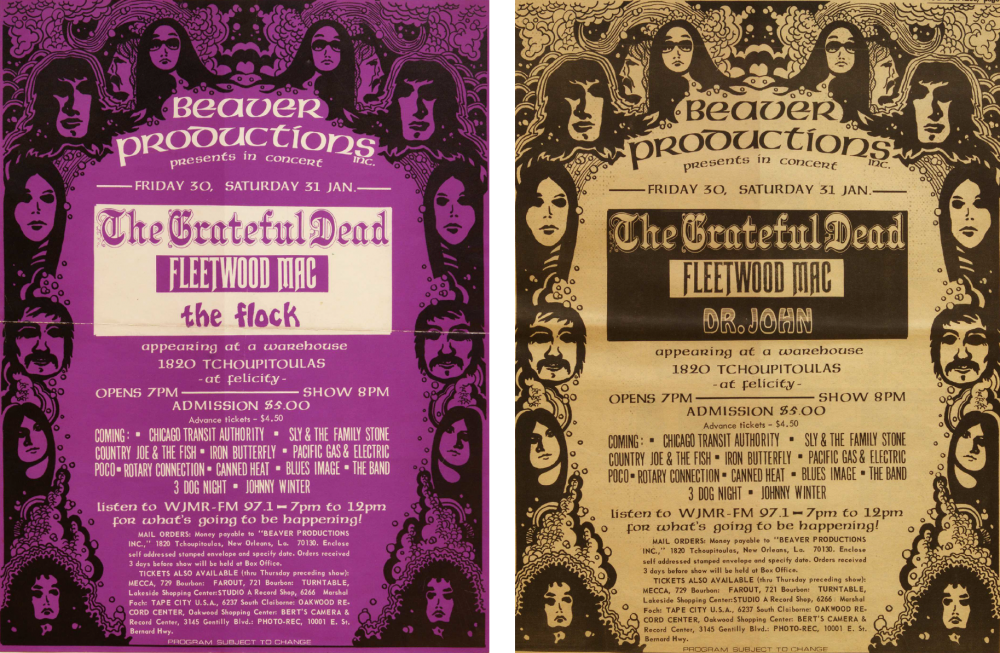

For fans of the kind of rock music featured at the love-ins, the fun was just beginning: January 30, 1970, saw the opening of the Warehouse, the legendary New Orleans live music venue. (The Grateful Dead played that opening weekend and were rewarded with a drug raid of their hotel. The incident made its way into their song “Truckin’,” with its reference to being “busted down on Bourbon Street.”)

Two different ads for the opening weekend of the Warehouse, a live music venue on Tchoupitoulas Street, show a change in the lineup leading up to the event. Dr. John was originally part of the bill with the Grateful Dead and Fleetwood Mac, as seen in the NOLA Express ad on the right, but his slot was replaced by the Flock, who went on to perform over two nights January 30–31, 1970. (Left: THNOC, 2013.0221.109. Right: THNOC, MSS 647 f. 423)

The New Orleans Pop Festival had a follow-up in 1971 with the Celebration of Life Festival, held north of Baton Rouge near the Atchafalaya River and organized by New Orleans Pop promoter Steve Kapelow. As chronicled by Alison Fensterstock for Rolling Stone, the festival was a fiasco, beset by logistical failures, poor infrastructure, rampant assault at the hands of the biker gang hired as security, and hard drugs. Three people died there, two from attempting to swim in the swollen river and one from a drug overdose.

Free concerts akin to the love-ins also popped up throughout the early 1970s—including the memorable Festival of Life held at the Fly, where the Allman Brothers Band, in town for a gig at the Warehouse, showed up to jam. As Cranston Clements of the band Twangorama recalled of the August 1970 show for the website Blackstrat.net, “Duane [Allman] walked up to a few of us mortals with a big smile on his face minutes before taking the stage, said, ‘I just did FIFTEEN reds!’ fell face-down in the grass, then picked himself up and proceeded to SMOKE that Les Paul!”

When the event ran past its sundown cutoff time and a security guard attempted to shut down the amp in the middle of “Whipping Post,” the band’s roadie “pushed the cop out of the way and ran off,” said Robinson. With the guard in pursuit of the roadie, the amp got plugged back in and the band finished its song.

The Allman Brothers Band showed up to play at a love-in on August 23, 1970. The band had played at the Warehouse the previous night and was in the habit of surprising fans at local jam sessions while on tour. (Photograph by Neil Burgard, image courtesy of Shelley Barberot Quintini, archivist, and Blackstrat.net)

New Orleans is certainly no stranger to different strokes, having spent much of its existence as an American anomaly, but in 1969 that longstanding cultural difference looked outward, as local bohemians engaged with the national counterculture movement. On one level, the love-ins were “just a group of people listening to music, doing whatever,” Gifford said. But beyond the free music and beer was a desire to challenge the systems of authority that had resulted in an intractable war that was killing so many of their peers.

“We thought we were gonna change the world,” said Robinson. “A lot of things changed, and a lot of things didn’t. Maybe we should start doing these festivals again. I think the pressure put on by youth culture helped end the war in Vietnam.”

(THNOC, MSS 647 f. 423)