Editor’s note: This story is released in conjunction with The Historic New Orleans Collection’s 2021 Symposium, “Recovered Voices: Black Activism in New Orleans from Reconstruction to the Present Day.” The interactive website includes books, stories, videos, and a March 5–7 program. Learn more here.

“Liberty has always had a hard road to travel, whenever prejudice was the consulted oracle. The United States will not be an exception to the rule, as long as race antipathy will be allowed to overshadow every other within our territory. But the obligation of the people is resistance to oppression.” –The Crusader, August 1891

One hundred and twenty-five years ago, the US Supreme Court delivered a 7-1 ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson, upholding a state’s right to segregate the races in “separate but equal” facilities.

The case originated in New Orleans as one of two test cases set up by a group of Creole of color activists. By appealing to the highest court in the land, the men behind Plessy v. Ferguson sought to halt the rolling back of major civil rights gains Black people achieved during Reconstruction. Their defeat in 1896 marked the end of an era of radical Black activism in New Orleans that began with the Civil War.  The plaintiff in the case, Homer Plessy, was born in New Orleans to French-speaking free people of color on March 17, 1863. Plessy came of age during a time that was in many ways significantly different from that of his parents, Adolphe and Rosa Debergue Plessy. Slavery no longer existed, which meant neither did the category, “free person of color.”

The plaintiff in the case, Homer Plessy, was born in New Orleans to French-speaking free people of color on March 17, 1863. Plessy came of age during a time that was in many ways significantly different from that of his parents, Adolphe and Rosa Debergue Plessy. Slavery no longer existed, which meant neither did the category, “free person of color.”

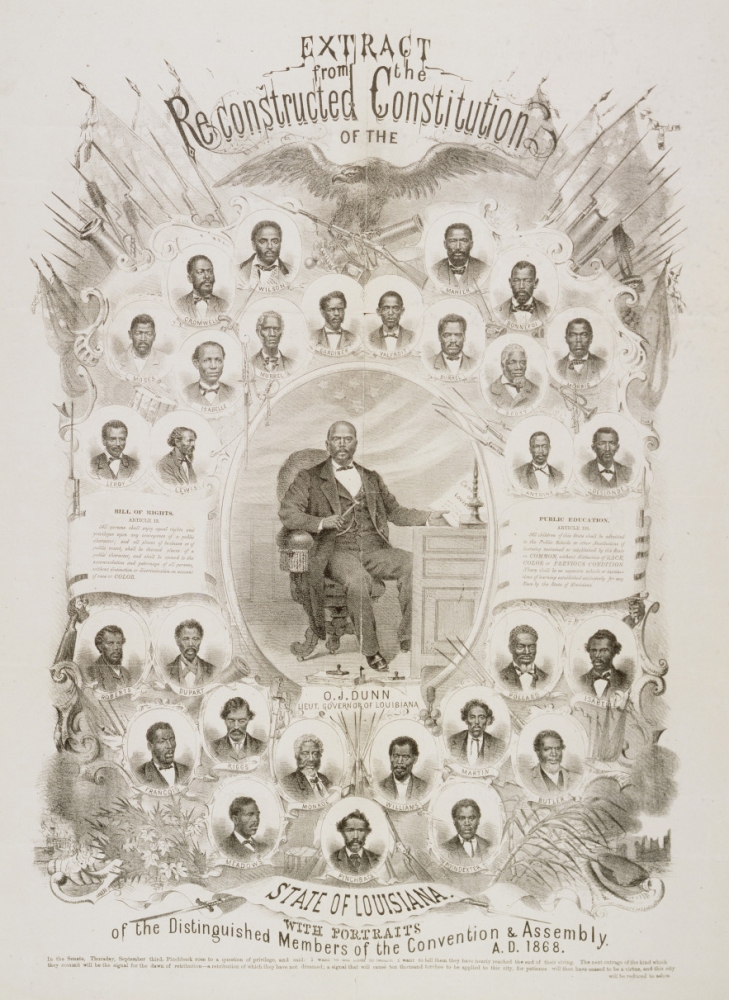

Plessy could ride integrated streetcars and attend integrated schools. He could look forward to voting and perhaps imagined running for elected office one day. These rights had been hard won by French-speaking Creole and English-speaking Black activists and their white Radical Republican allies. The 1868 Louisiana constitution, which enshrined these “civil, political, and public rights” for all citizens, marked the culmination of their efforts.

Louisiana's reconstructed constitution was one of the most progressive of its kind, providing for Black male suffrage and equal rights for all Louisianians in public education and accommodations. This commemorative lithograph depicts the African American men elected to public office in 1868. (THNOC, 1979.183)

Yet, as Homer Plessy entered his teen years, a compromise resolving the contested 1876 presidential election ended Reconstruction, and conservative white Democrats quickly gained power in Louisiana. The new government began to dismantle advances in racial equality, beginning with integrated public schools.

Activists in New Orleans fought the resegregation of schools through mass protests and lawsuits but to no avail. A new state constitution approved in 1879 eliminated language guaranteeing equal rights to public places and ended public school integration.

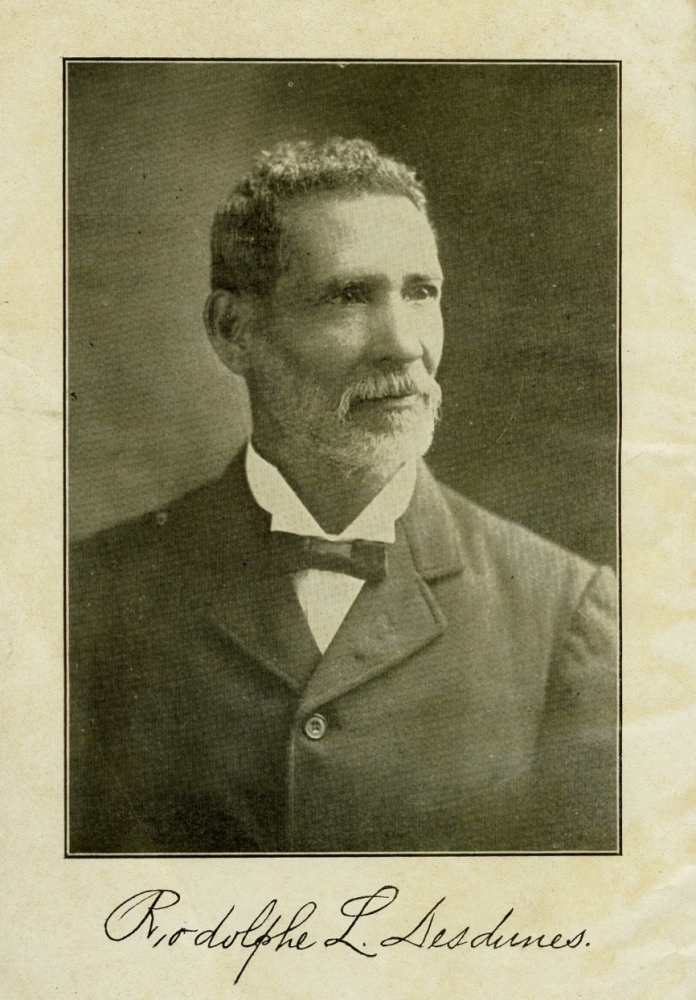

In the face of these setbacks, a multigenerational group of Creole activists continued to organize during the 1880s. Stalwarts of the Reconstruction era, including newspaper editor Paul Trevigne, joined forces with emerging leaders like Rodolphe L. Desdunes and Louis A. Martinet. Now a young man in his 20s, Homer Plessy was part of this next generation of activists.

These men revitalized pre–Civil War institutions and created new ones. In 1886, for example, a group established the Justice, Protective, Educational, and Social Club to make sure “our rights as citizens of this State and of the United States [are] protected and respected.” The following year, Plessy, who was working as a shoemaker at the time, became vice president of the club.

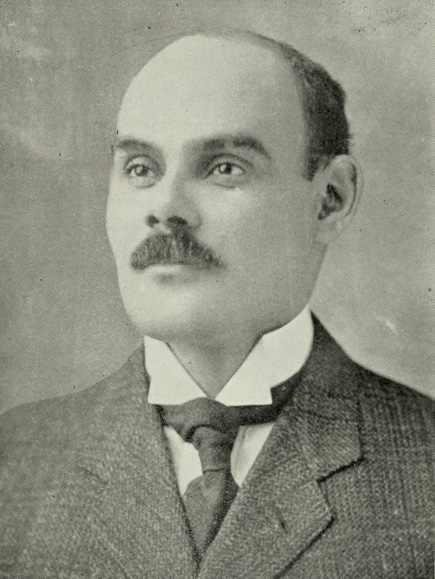

Afro-Creoles like Rodolphe Desdunes emerged in a new generation of activists during the 1880s. (THNOC, 59-110-L)

Afro-Creoles like Rodolphe Desdunes emerged in a new generation of activists during the 1880s. (THNOC, 59-110-L)

Martinet, a notary with degrees in law and medicine from Straight University—a historically Black school that merged with New Orleans University in 1935 to form Dillard University—launched a newspaper in 1889, aided by several members of the Justice, Protective, Educational, and Social Club. Printed in French and English, the Crusader followed in the footsteps of two earlier Black-owned activist papers, L’Union and the Tribune.

Desdunes, who also graduated from Straight’s law program, wrote for the Crusader and eventually served as editor-in-chief. Veteran writer and activist Trevigne frequently contributed as well.

The Crusader spoke out against violence and discriminatory treatment toward Black people. It denounced efforts to make distinctions between the races, arguing that Louisiana’s mixed population made this unfeasible. The paper also closely monitored the legislature for new laws that chipped away at Black civil rights. During the legislative session of 1890, the Crusader focused its attention on a bill known as the Separate Car Act.

First introduced in May, the Separate Car Act mandated that railroad companies enforce segregated seating in their trains with designated “white” and “colored” cars. The Crusader’s contributors recognized the injustice of this act as well as the arbitrary enforcement of a law based on visible cues of race.

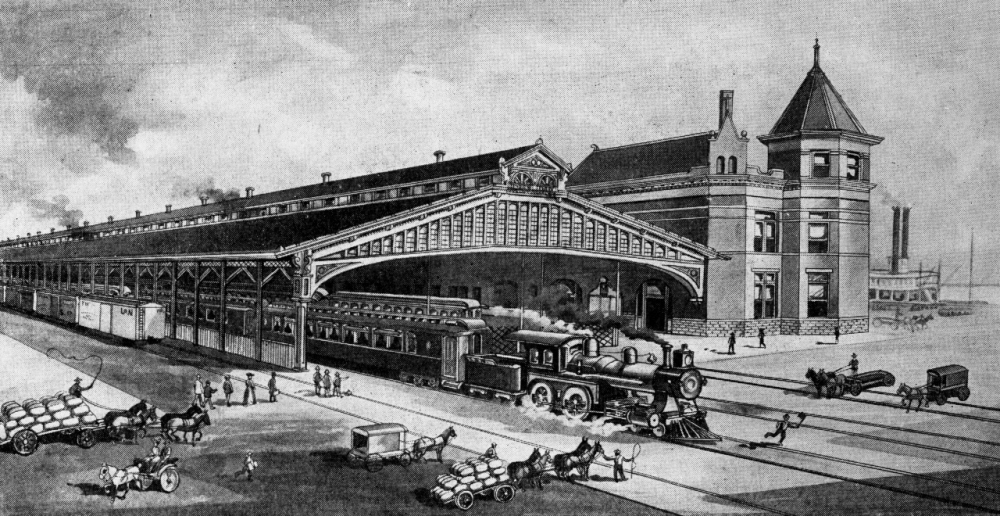

After the Separate Car Act was passed, the first challenge to the law took place on the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, whose depot is depicted here. (Courtesy of the Vieux Carré Survey).

“Every honorable person knows,” wrote Desdunes, “that the law was passed to discriminate against the colored people so as to degrade them.” The paper also warned that allowing the Separate Car Act to go unchallenged would embolden white legislators to further erode the rights of African Americans. The Crusader protested the act, calling for boycotts of the railroad companies and the formulation of a test case to challenge the law in court.

The Louisiana branch of the American Citizens’ Equal Rights Association (ACERA) immediately opposed the bill. ACERA members, including Crusader staff, traveled to Baton Rouge to protest the law’s passage. Despite their efforts, the act passed on July 10. ACERA considered additional ways to counter the Separate Car Act, but Creole leaders deemed the organization’s tactics ineffectual and embarked on their own orchestrated fight against the law.

In September 1891, a group of eighteen men formed the Comité des Citoyens (Citizens’ Committee) for the Annulment of Act No. 111, Commonly Known as the Separate Car Law. Representing several generations of activists, the members included business owners, teachers, writers, and lawyers. The committee’s membership overlapped with Crusader staff and the Justice, Protective, Educational, and Social Club. While Creoles predominated, a few members were English-speaking Black men.

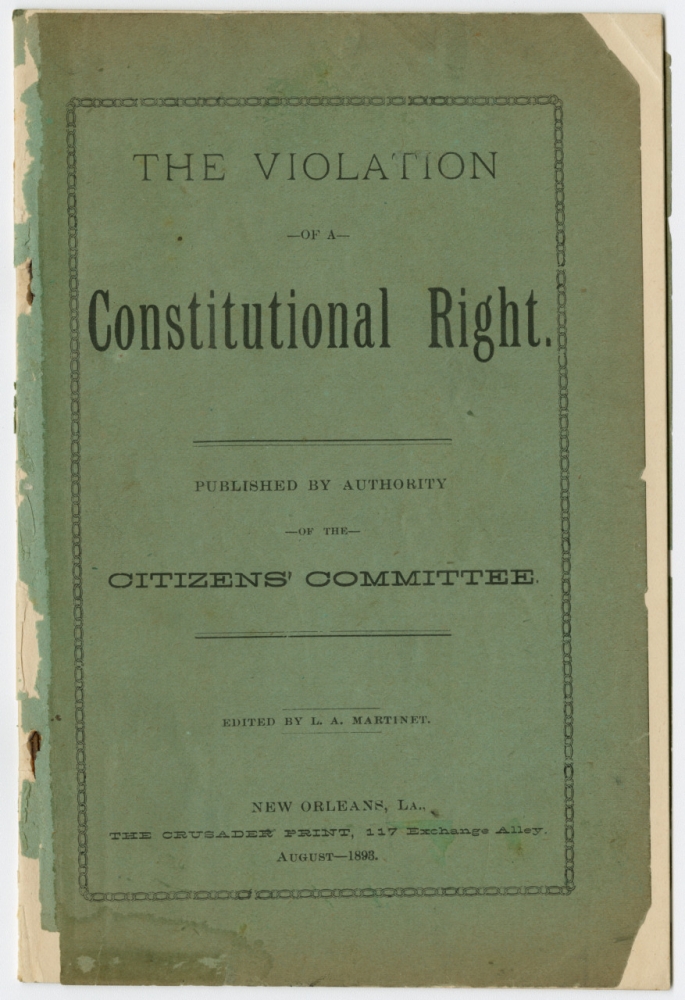

A pamphlet titled The Violation of a Constitutional Right was published by the Citizens’ Committee in 1893. (THNOC, 58-70-L)

A pamphlet titled The Violation of a Constitutional Right was published by the Citizens’ Committee in 1893. (THNOC, 58-70-L)

The committee sought to overturn the Separate Car Act through the legal system. Similar to arguments made in the Crusader, the committee claimed that “unless promptly checked by the strong power of the courts, the effects of that unconstitutional and malicious measure will be to encourage open persecution, and increase, to a frightful degree, opportunities for crimes and other hardships.”

Using its connections to Black benevolent associations, labor unions, religious groups, and other organizations, both local and national, the Citizens’ Committee raised $3,000 to fund their fight.

Martinet and Desdunes devised the committee’s strategy to challenge the constitutionality of the law through test cases. To assist in their plan, Martinet recruited Albion W. Tourgée, a white lawyer in New York. The Union veteran and former Republican judge in North Carolina remained an outspoken proponent of equal rights as a writer and organizer in the years following Reconstruction’s end.

As Tourgée worked on the legal strategy from New York, the Citizens’ Committee enlisted a local white attorney, James C. Walker, to assist in New Orleans. With their counsel and plan in place, the Citizens’ Committee set up two cases to contest the Separate Car Act.

The first case involved the planned arrest of Desdunes’s son, Daniel (inset), on an interstate train trip. The Citizens’ Committee made arrangements with the Louisiana and Nashville Railroad in advance. Unhappy with the financial burden of running separate cars, the company agreed to cooperate. The Committee then hired private detectives to make the arrest.

On February 24, 1892, Daniel Desdunes bought a ticket to Mobile, Alabama, and boarded the first-class “whites-only” car. As planned, Desdunes refused to move to the “colored car” when confronted by a railroad employee. The train stopped to allow the detectives to board and arrest Desdunes for violating the Separate Car Act. The Citizens’ Committee paid Desdunes’s bond.

Daniel Desdunes’s case came before Judge John Ferguson, who dismissed the charges in July. Citing a recent decision in a Louisiana Supreme Court case, Judge Ferguson ruled that regulation of interstate travel fell under the federal government’s domain, and, therefore, the Separate Car Act could not be applied to interstate trips.

The Crusader cheered, “Jim Crow is Dead as a door nail.”

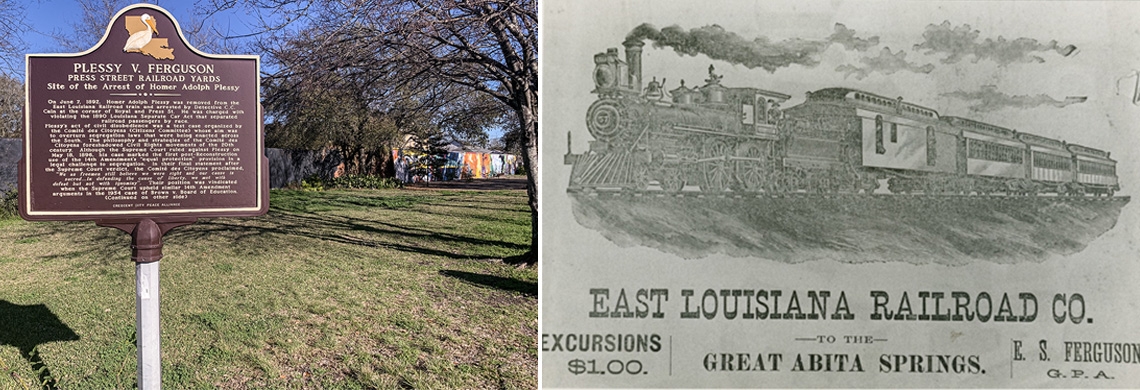

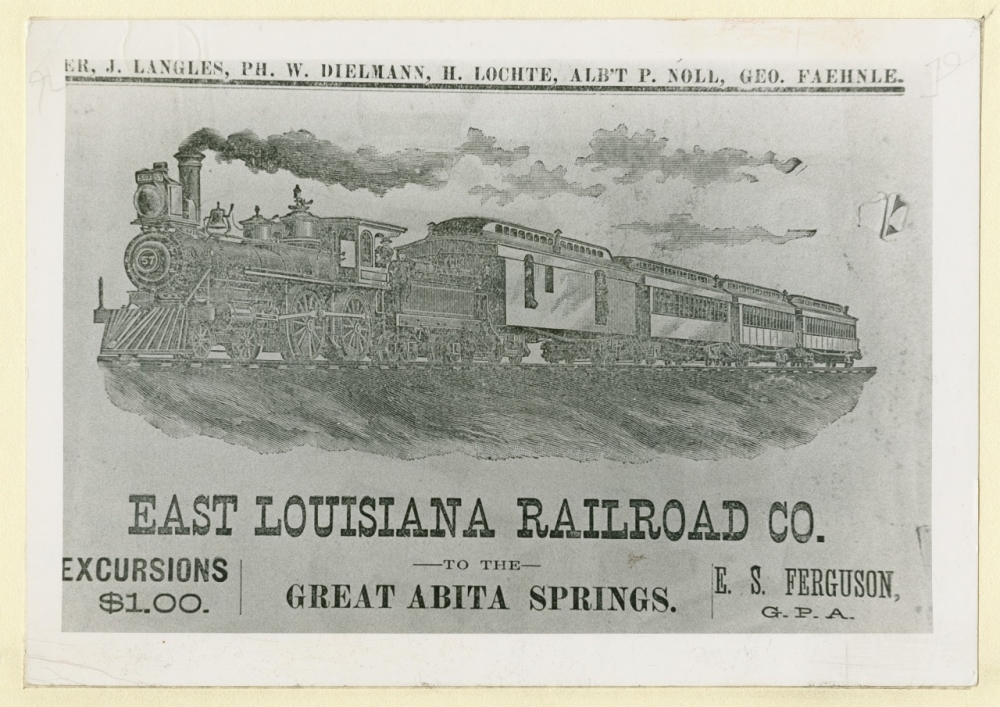

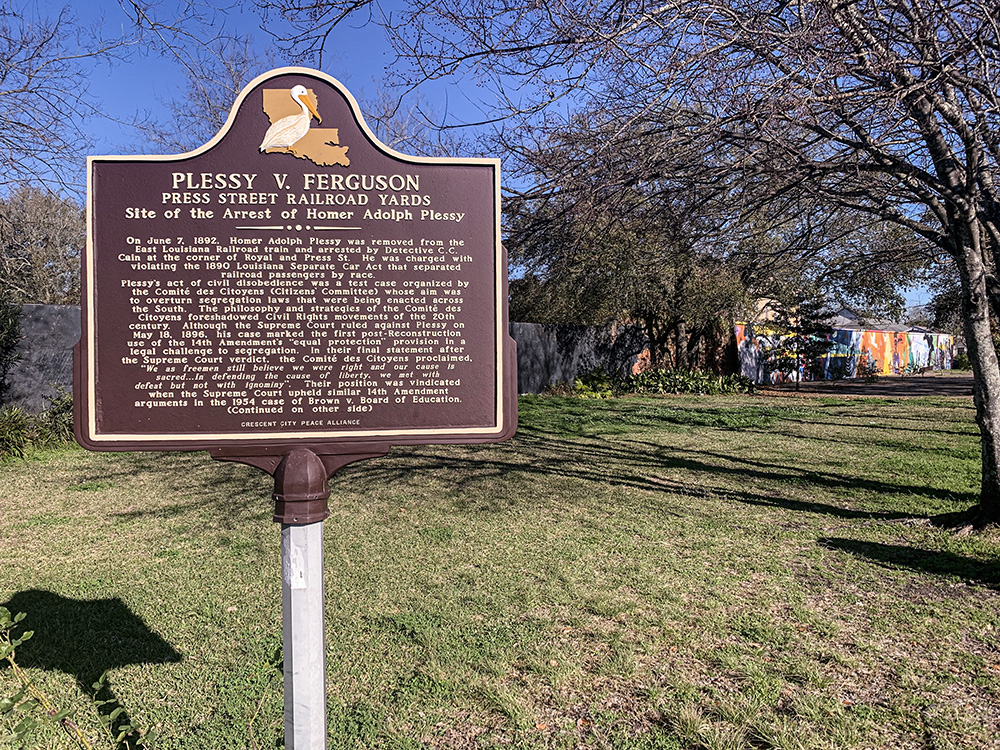

The Committee’s second case required Homer Plessy to get arrested in the “white” car on an intrastate trip. On June 7, 1892, Plessy booked a ticket on the East Louisiana Railroad to travel across Lake Pontchartrain. His planned arrest occurred not long after the train left the Press Street station.

Photograph of an advertisement for the East Louisiana Railroad Company. In June 1892, Homer Plessy of New Orleans purchased a ticket on the East Louisiana Railroad and took a seat in a whites-only car. (THNOC, 1974.25.37.57)

Plessy’s case also landed on Judge Ferguson’s docket. Walker, the Citizens’ Committee attorney, asked that the charges against his client be dismissed, arguing that the Separate Car Act violated the 14th Amendment by making “invidious distinction and discrimination based on race.”

Judge Ferguson disagreed. In November, he ruled that for travel within Louisiana, the Separate Car Act remained constitutional because equal accommodations were provided to white and Black passengers.

Walker immediately appealed, sending the case before the Louisiana Supreme Court. As the Citizens’ Committee expected, the justices handed down a decision in favor of the state.

Defeat at the state level prompted the Citizens’ Committee to turn to the federal judiciary. Committee members understood the severe consequences that a ruling against Plessy could have for people of African descent but felt this was a risk they must take. Rodolphe Desdunes explained: “We believe that it is more noble and worthy to fight nonetheless, rather than to show oneself passive and resigned. Absolute submission augments the oppressor’s power and creates doubts about the sentiment of the oppressed.”

A mural by Ian Wilkinson stands on Royal Street, near the modern-day site of Plessy's arrest. It depicts Louisiana's one-time acting governor, PBS Pinchback, whose portrait is often misidentified as Plessy, and the artist's interpretation of what Plessy may have looked like. (Photograph by Eli A. Haddow)

Tourgée filed the case with the United States Supreme Court in October 1895. Eight justices heard the arguments in Plessy v. Ferguson the following spring. Tourgée sought to demonstrate that the Separate Car Act violated the 13th and 14th Amendments. By creating racial distinctions among citizens, he argued, segregated seating “perpetuat[ed] the stigma of color” and denied Black people equal protection under the law.

Tourgée also pointed out the absurdity of enforcing strict racial categories given the undeniable existence of widespread racial mixture, an argument long espoused by Creole activists. Indeed, the Citizens’ Committee purposefully chose Plessy and Daniel Desdunes for the test cases because of their “white” physical appearance. Tourgée argued that Plessy’s racial ambiguity proved that a law with the premise of separating two distinct groups—“whites” and “coloreds”—was untenable.

This image of the US Capitol was taken between 1885 and 1920. The Supreme Court heard arguments at the US Capitol, in a room that formerly housed the US Senate. (THNOC, gift of Joy Segura, 2004.0096.96)

On May 18, 1896, the Supreme Court delivered its decision, upholding Judge Ferguson’s initial ruling that “separate but equal” was indeed constitutional. In the majority opinion, Justice Henry Billings Brown claimed that nothing about “enforced separation . . . stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority.” If Black people felt that way, it was because they “[choose] to put that construction on it.”

Regarding the 14th Amendment, Brown wrote that the law protected only “political equality” not “social equality.” Thus, “if one race be inferior to the other socially,” which Brown believed to be true, “the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.” As to how an individual’s race was categorized, Brown declared that states had the right to their own legal definitions.

Justice John Marshall Harlan delivered the sole vote in favor of Plessy. In his dissent, Harlan disagreed with the majority’s narrow interpretation of the 13th and 14th Amendments, believing that “if enforced according to their true intent and meaning” the amendments “will protect all the civil rights that pertain to freedom and citizenship.” He echoed Tourgée’s argument that the Separate Car Act “puts the brand of servitude and degradation upon a large class of our fellow citizens, our equals before the law.”

Warning that legalized segregation would cause “race hatred,” Harlan forcefully ended his opinion by putting the lie to the “separate but equal” doctrine: “The thin disguise of ‘equal’ accommodations for passengers in railroad coaches will not mislead any one, nor atone for the wrong this day done.”

A plaque at the modern-day site of Plessy's arrest commemorates the role of the Citizens' Committee in the struggle for civil rights. (Photograph by Eli A. Haddow)

The Citizens’ Committee’s fear that the Separate Car Act would lead to increased forms of segregation and discrimination came true after the Plessy ruling. The Supreme Court’s decision officially sanctioned segregation laws, which proliferated over the next decades throughout the South and beyond.

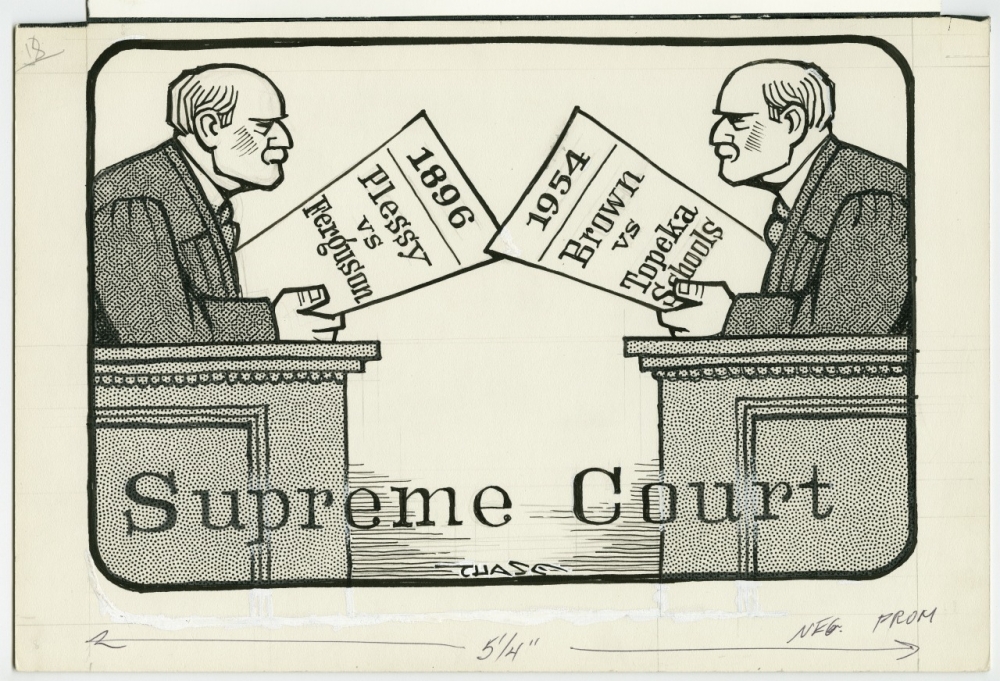

By the turn of the 20th century, the Louisiana legislature had passed laws that segregated most public accommodations. White Louisianians enforced the new restrictions through violence against Black Louisianians. The Supreme Court’s ruling would not be overturned until the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case.

A 1970s cartoon by John Churchill Chase recalls Plessy v. Ferguson and the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education, which reversed the Plessy ruling. (THNOC, Gift of John Churchill Chase and John W. Wilds, 1979.167.18 a)

The Citizens’ Committee disbanded not long after the Supreme Court ruled in favor of racial segregation. In a final statement, the Committee explained that “notwithstanding this decision, which was rendered contrary to our expectations, we, as freemen, still believe that we were right, and our cause was sacred. . . . In defending the cause of liberty, we met with defeat, but not with ignominy.”

Even in the face of bitter disappointment, Creole activists maintained their pride and determination to fight for their rights as humans and as citizens. Although the struggle to realize their vision of a society built on equality and free of racial prejudice fell short, it left a powerful legacy for future Black activists in Louisiana.

Explore Black activism in New Orleans through our Symposium 2021 website.