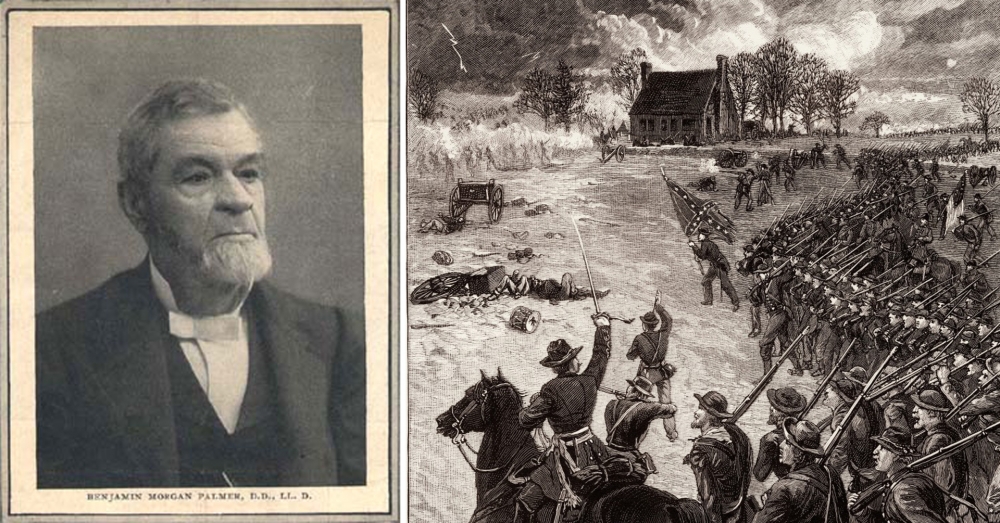

Twenty-three days after the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln, Rev. Benjamin Morgan Palmer (inset) delivered a dramatic Thanksgiving Day sermon to his congregation at the First Presbyterian Church in New Orleans. “In determining our duty in this emergency, it is necessary that we should first ascertain the nature of the trust providentially committed to us,” he said, addressing the abolitionist threat Lincoln’s election represented. “A nation often has a character as well-defined and intense as that of the individual. … If, then, the South is such a people, what, at this juncture, is their providential trust? I answer, that it is to conserve and to perpetuate the institution of domestic slavery as now existing.”

The latter line, emphasized in italics in printed copies of the nearly 7,000-word sermon, became a rallying cry within the states that would soon form the Confederacy. Tens of thousands of copies of the speech were quickly printed and circulated throughout the South, while regional newspapers published Palmer’s words, often alongside enthusiastic commentary. Palmer elevated the defense of slavery to a godly duty: “We defend the cause of God and religion,” he declared, the emphasis added in the printed speech. “The Abolition spirit is undeniably atheistic.” Palmer argued for white supremacy on moral grounds, using racist stereotypes to insist that “no calamity can befall [the black race] greater than the loss of that protection they enjoy under this patriarchal system.”

An 1866 stereograph shows Palmer's First Presbyterian Church on Lafayette Square, where the preacher gave his Thanksgiving Day sermon in 1860. (The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2010.0095.8)

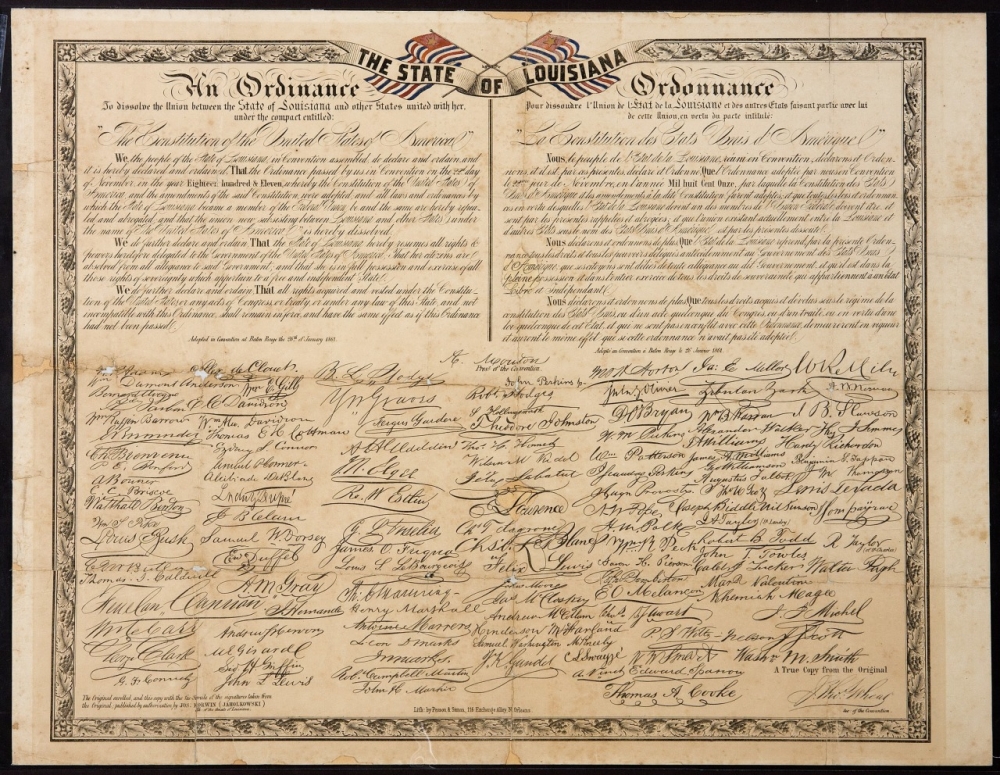

Already a fixture in the South, Palmer gained national fame—he went viral, in an 1860 sense—just as Southern states were deciding how to respond to Lincoln’s election. Three weeks after the speech South Carolina became the first state to secede, its leaders declaring that “increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding states to the institution of slavery” compelled their action. Mississippi, Florida, Alabama and Georgia soon followed South Carolina in secession, and Louisiana joined on January 26, 1861.

A broadside of Louisiana’s ordinance of secession in 1861 followed Palmer's fiery Thanksgiving Day sermon. (The Historic New Orleans Collection, 86-2251-RL)

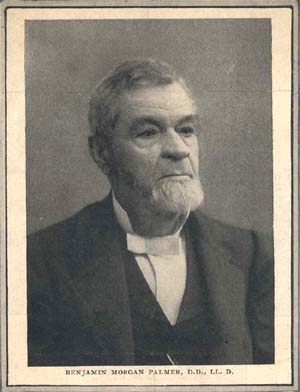

In 1977 historian Timothy F. Reilly wrote that Palmer’s Thanksgiving speech “perhaps did more to unify the secessionist cause than any other single clerical sermon or political address.” During the Civil War, Palmer frequently preached to soldiers, before they departed for battle and sometimes in the field. He characterized theirs as “a war of civilization against a ruthless barbarism” while assuring that “the pen of history shall write the story of your martyrdom.” After their defeat, Palmer became a leader in the “Lost Cause” movement, shifting his focus to framing the rebellion as heroic. He delivered a glowing eulogy of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, who became a Lost Cause icon.

Later in life, Palmer continued to lionize the Confederate cause and fixate on race—in 1884 he lectured a mostly black audience on the importance of racial purity—earning the reverence of white Southerners. He was struck and killed by a streetcar four years later, after which city officials named Palmer Park, in the Carrollton neighborhood, in his honor.

A version of this article previously appeared in the Historically Speaking column of the New Orleans Advocate.