If you’ve been on Instagram or TikTok recently, then you’ve probably come across women asking the men in their lives a very important question: How often do you think about the Roman Empire? Without fail, the men respond that they think about the Romans often—monthly, weekly, even daily. And without fail, their girlfriends and wives are surprised to find that, apparently, all roads and thoughts lead to Rome.

The meme’s comedy relies on a gendered gap in interest more than on the specific topic of interest. Of course, not all men regularly ruminate on Rome, and many women ponder Pompeii. And, as any real ancient European history aficionado will point out, the Roman Kingdom, Roman Republic, and Roman Empire weren't all the same thing. But what the viral inquiry taps into is that even if we don’t actively think about ancient Rome every day, it has shaped our thoughts and, as a result, our world.

From Carnival float themes to street names and architecture, the Roman Empire also shaped New Orleans and the surrounding region. Here are some of the Rome-related items in The Historic New Orleans Collection’s holdings.

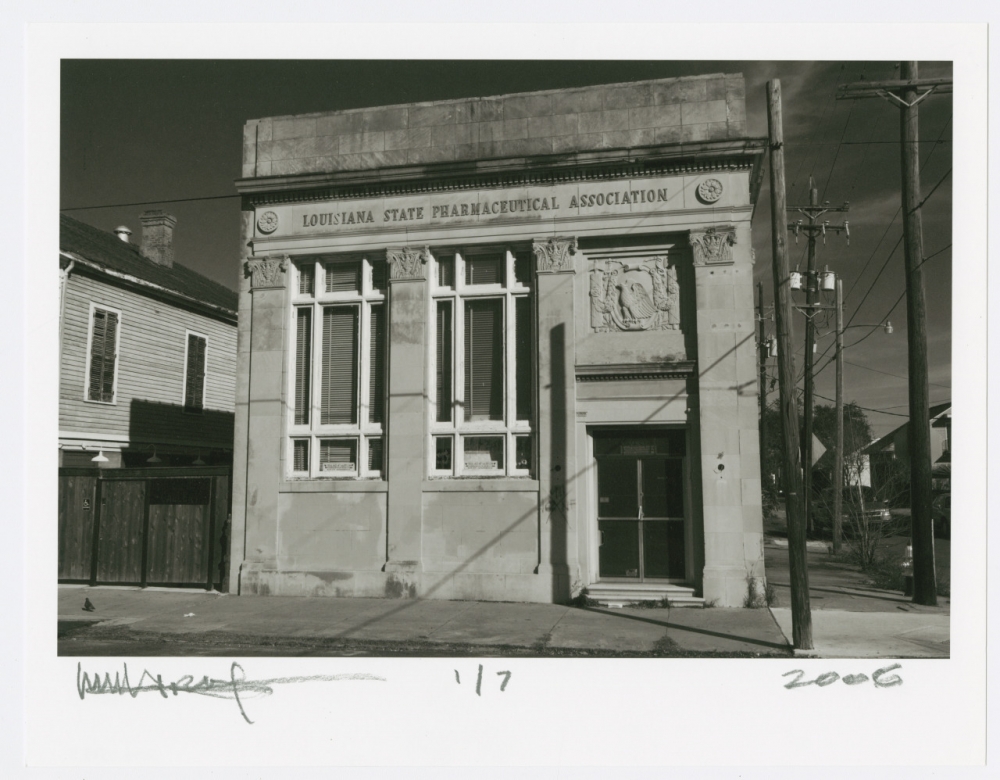

Emile Weil’s Neoclassical Buildings

The stone façade of the Louisiana State Pharmaceutical Association building at 2337 St. Claude, constructed in 1926, features ornate capitals and a relief of an eagle above the doorway. (THNOC, gift of William Karam Jr., 2018.0308.5)

The Vieux Carré might be famous for its French- and Spanish-style architecture and wrought iron balconies, but New Orleans is also home to a wide selection of neoclassical buildings, which draw inspiration from ancient Greece and Rome. Some of the city’s most notable neoclassical structures were designed by architect Emile Weil (1878–1945). Born in New Orleans, Weil studied at Tulane, then worked as a draftsman. In 1899, he established his own practice, soon becoming one of the most sought-after architects in the region. Weil was well versed in the history of European architecture and stayed up to date on national and international trends, incorporating classical and Renaissance forms as well as Beaux-Arts and Baroque styles.

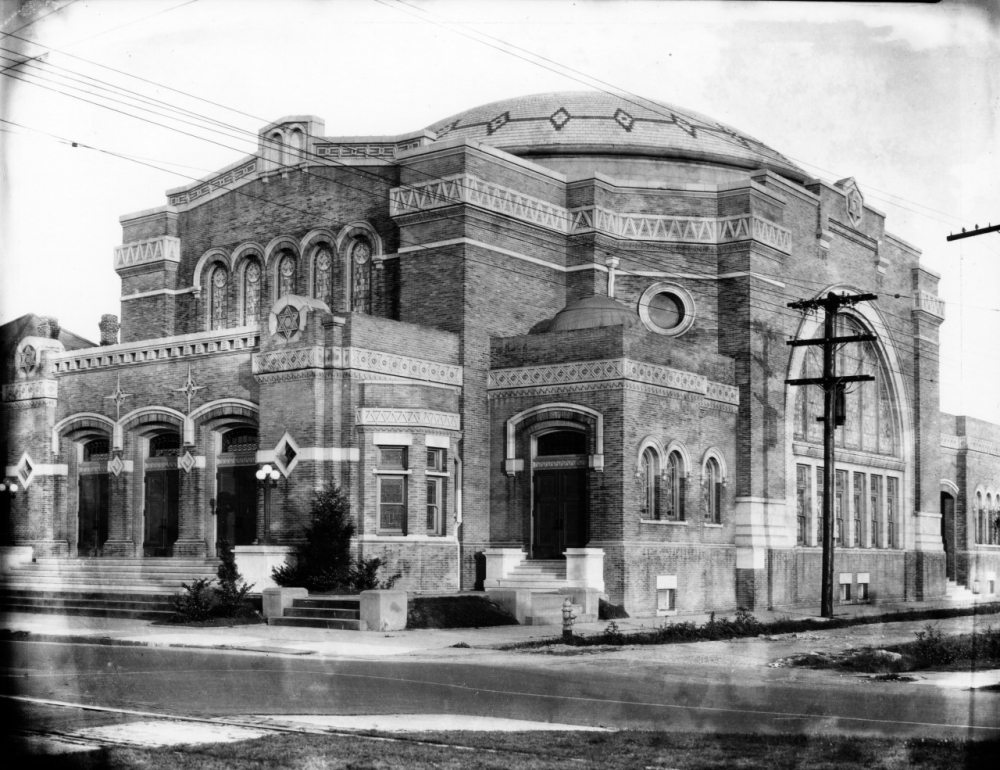

(Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.89.7482)

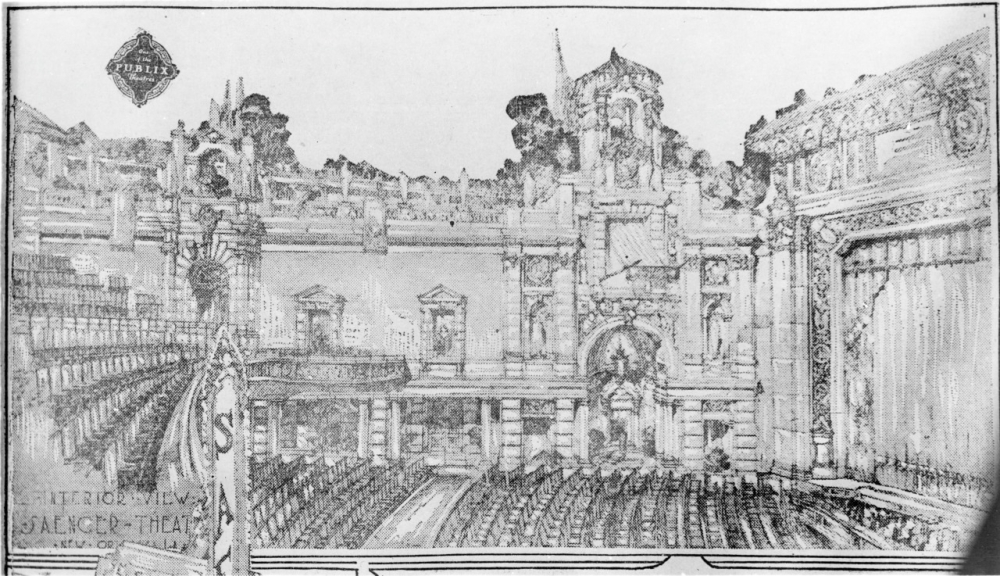

Weil designed the inside of the Saenger Theatre, pictured here in a ca. 1924 architectural rendering, to resemble a Baroque Italian courtyard. Life-size statues of toga- and palla-clad standing figures recall ancient Roman sculptures. Painted to resemble a night sky with twinkling lights arranged in the shape of constellations, the building’s interior feels like an open-air amphitheater in the Italian countryside.

(Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.89.7475)

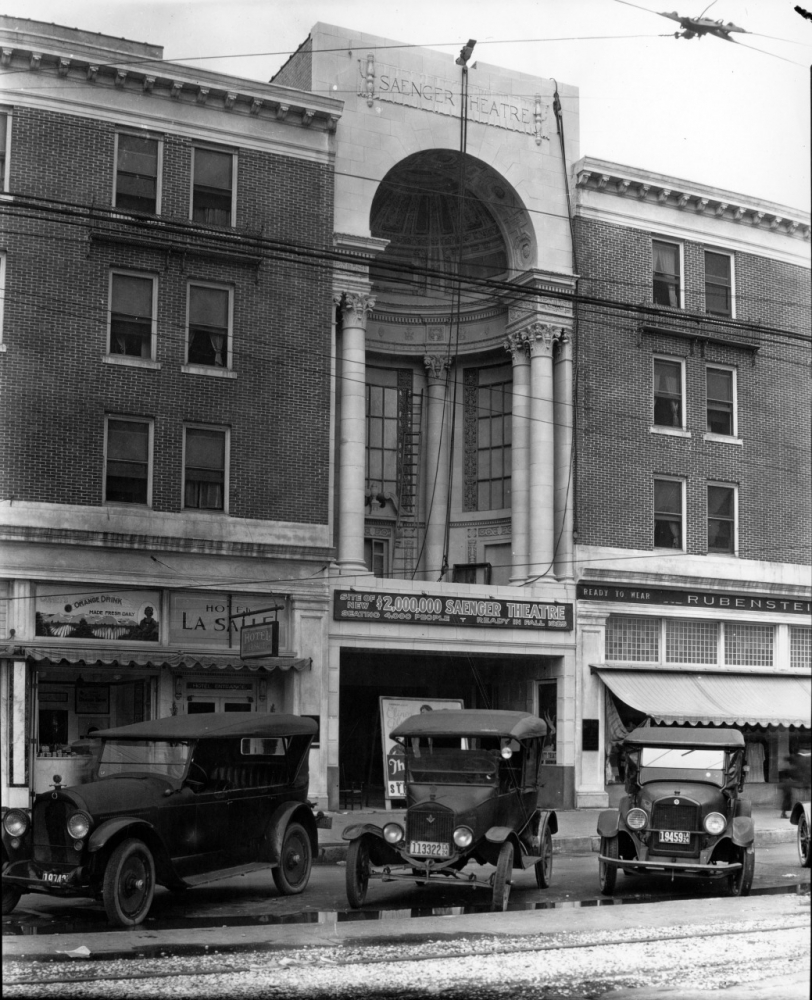

The front of the theater, pictured here from Canal Street while it was under construction ca. 1924, shows features that define neoclassical architecture, including tall columns, symmetry, and a dome.

(Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.2458)

Touro Synagogue on St. Charles Avenue is home to the United States’ oldest Jewish congregation outside of the 13 colonies. Weil won a design competition for the building, which was dedicated in 1909. To incorporate the congregation’s Sephardic heritage and differentiate the building from Christian houses of worship, Weil incorporated neo-Byzantine elements like the low dome and geometric reliefs. Still, the columns, symmetry, and use of stone are reminiscent of the Roman Empire, of which the Byzantine Empire was a continuation.

Loqui Latin

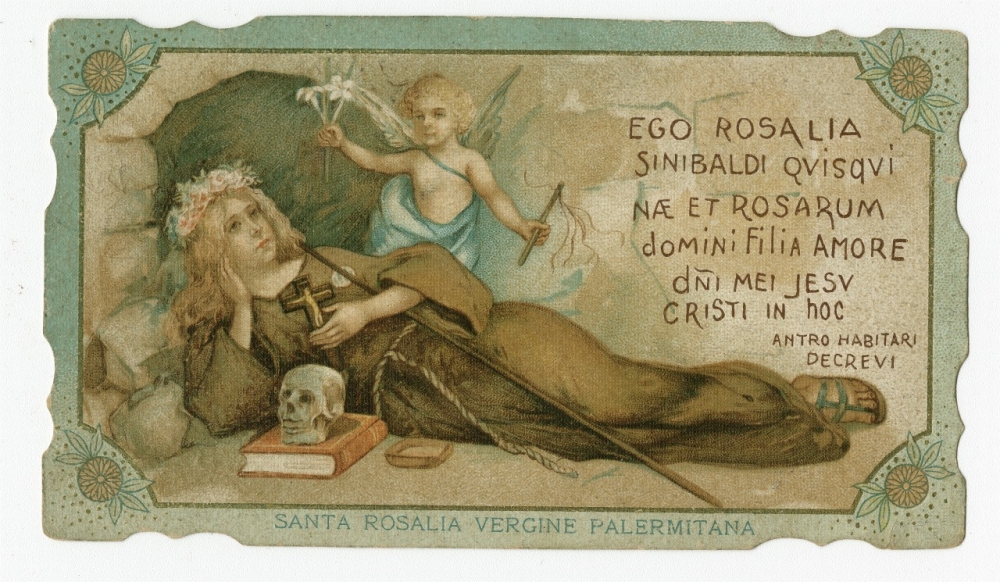

(THNOC, 2003.0149.6)

It wasn’t until the first Sunday of Advent in 1964 that the Roman Catholic Church (heavy on the Roman) introduced vernacular mass. Until then, the worshippers heard mass and said prayers in Latin. This 1885 prayer card was likely owned by first- or second-generation Sicilian New Orleanians. Depicting Saint Rosalia, the Virgin of Palermo, the card includes text in both Latin and Italian.

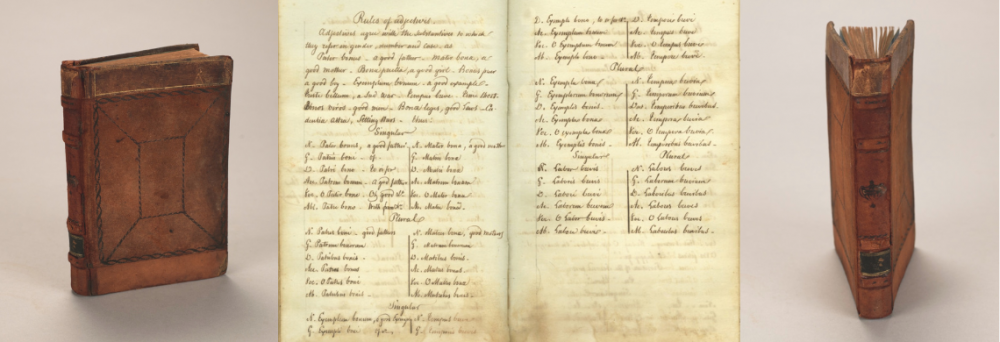

Felix Grima Latin lessons book (gift in memory of Alfred Grima Johnson, THNOC, 2011.0080)

In the 19th century, learning Latin was a prerequisite for the educated. Wealthy families hired private tutors to teach their children classical Latin vocabulary and grammar, and children lower down the social ladder learned Latin from nuns and clergy at Church-run schools. Dated 1864–65, the 147 handwritten pages of this book include lessons on verb declension and rules for using adjectives.

Peculiar Pecunia

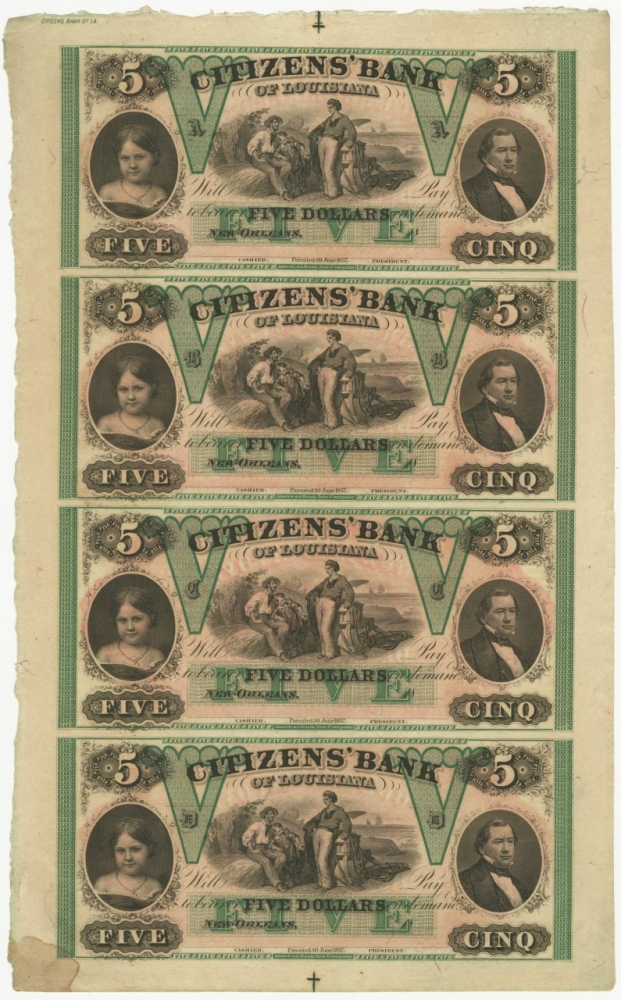

Citizens’ Bank of Louisiana at New Orleans uncut sheet of five-dollar notes. (THNOC, 1974.15.6)

Two millennia after Emperor Gordian III started minting the silver denarii, Roman references are still common on coins and banknotes across the globe. Before the Civil War, the Citizens’ Bank of Louisiana incorporated Roman numerals into the art on their bank notes. On the five-dollar notes above, two green Roman numeral Vs flank the central illustration. On the front of the 10-dollar note below, the Roman numeral X is at top left; on the back of the note, Xs are incorporated into the red background. (Because the French word for ten, dix, was printed on their backs, these notes were called “dixie notes,” commonly believed to be the origin of the term “Dixieland.”)

Citizens’ Bank of Louisiana 10-dollar note, front (top) and back (bottom) (THNOC, 1974.15.13)

Random Roman References

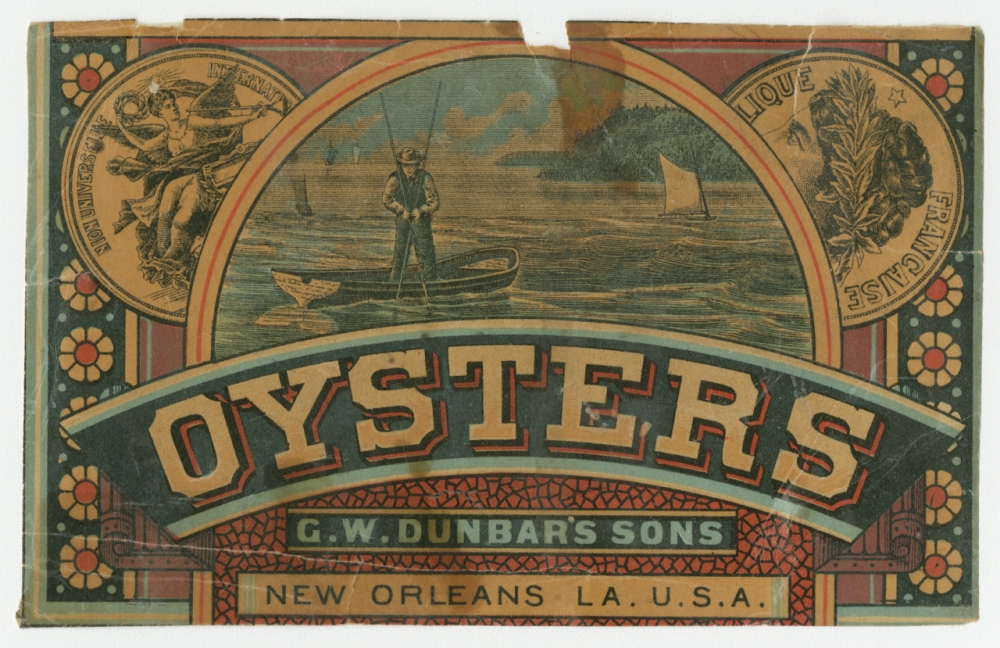

Food crate label for Dunbar’s grocery store, 1881-1907 (Gift of Mr. Harold Schilke and Mr. Boyd Cruise, THNOC, 1953.119.1)

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, South Louisianans used Rome as inspiration for art, including in advertisements. In the food crate label above, the medallion on the left features a winged Neoclassical figure blowing a horn while the one on the right shows a woman in a laurel wreath.

(THNOC, 2014.0050.34)

The cover of this sheet music to E.T. Paull’s 1903 composition “The Burning of Rome” shows the city with a man, probably Emperor Nero, strumming the lute while buildings burn. As per the explanatory note inside, the composer intended the first part of the March “to represent a grand gala... in the Colliseum.” Descriptive headings like “Dash of the Charioteers for Position” are clear references to ancient Rome. Though the sheet music was published in New York, it’s notable that the Rome-inspired work ended up in New Orleans, where it was saved for more than a century and a half before being acquired by THNOC.

(THNOC, 1974.25.9.327)

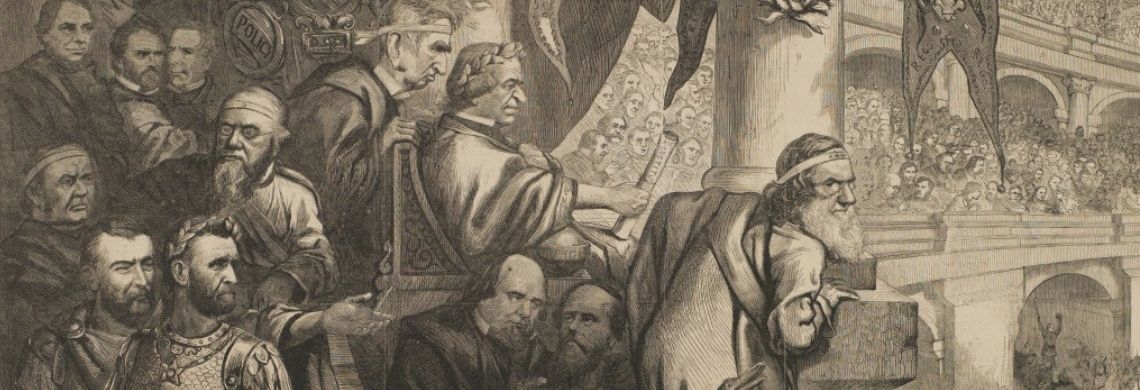

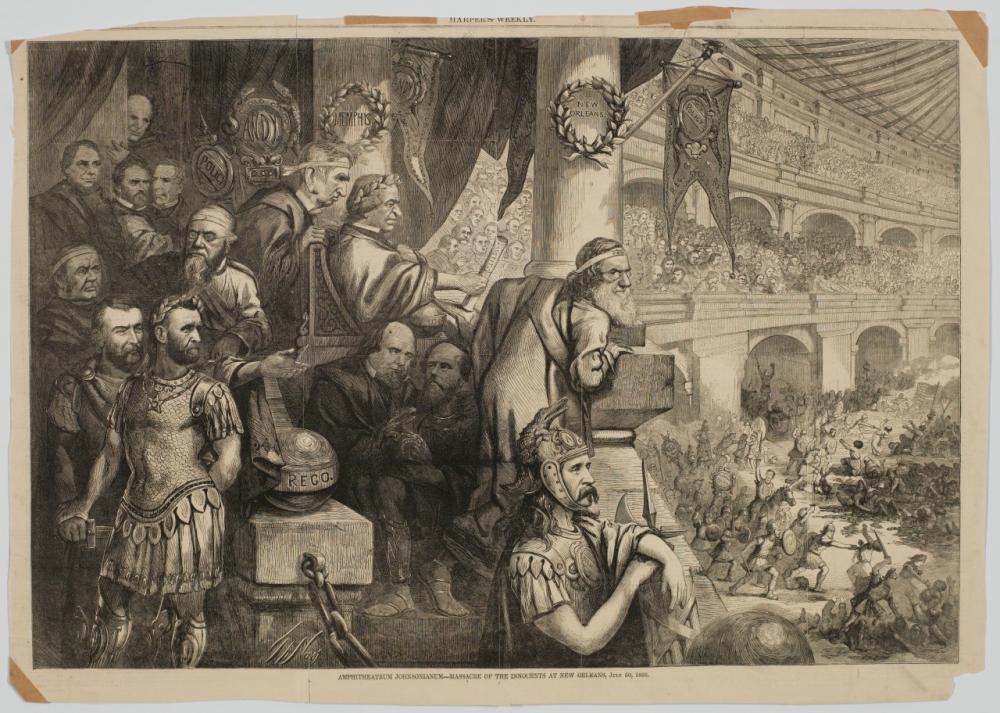

In the period before and immediately after the Civil War, Ancient Rome was commonly used as allegory for contemporary politics. The above illustration from an 1867 edition of Harper’s Weekly, entitled “Massacre of the Innocents at New Orleans,” critiques local and national politicians for failing to intervene in the New Orleans Massacre of 1866, when a mob of white rioters attacked a peaceful demonstration of Black freedmen. President Andrew Johnson is a Roman emperor impassively watching New Orleans Mayor John Monroe on horseback lead a police charge against Black freedmen. General George Armstrong Custer (in a Roman helmet and armor), Ulysses S. Grant (at lower left, also in Roman military garb), New Orleans Military Commander General Phil Sheridan, and Vice President Schuyler Colfax are among the large group of politicians who sit and watch with Johnson.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.