Researching a makeover, teams of Disney Imagineers have made multiple trips to The Historic New Orleans Collection and the Williams Research Center during the past couple of years. Their goal is to transform the theme park attraction Splash Mountain into an immersive journey into the New Orleans of the 2009 animated film The Princess and the Frog. Tiana’s Bayou Adventure is expected to debut in California’s Disneyland and Florida’s Walt Disney World Magic Kingdom in the later months of 2024.

One of the research trips coincided with the 2022 exhibition Making Mardi Gras, which took visitors behind the scenes of every kind of Carnival celebration, from the rolling bead dispensers and faux royalty floating down the uptown route to the street-level majesty of Mardi Gras Indians. The exhibit evidently made a deep impression, both on the Imagineers and the eventual ride. When Disney later returned to New Orleans with a contingent of entertainment reporters in tow, they asked THNOC for a Carnival-themed show-and-tell of some of the earlier sights they’d seen in Making Mardi Gras.

As we wait for the first log to load at Tiana’s Bayou Adventure, here’s a look at some of the objects that were on view that day in May 2023.

Rex breastplate (1893)

(THNOC, 2012.0100.1)

Since its founding in 1872, the Krewe of Rex has crowned one of its members as “King of Carnival.” In 1893, prominent businessman John Poitevent was the “Monarch of Merriment.” He rode behind the title float (“Fantasies”) and the boeuf gras (the fatted bull of Carnival, represented by a live bull in early Rex parades) wearing an elaborate costume that included this bronze breastplate. The red and green glass stones and rhinestones on the front, arranged in the shape of a fleur-de-lis, match the breastplate’s belt as well as Poitevent’s crown and scepter.

Chief Howard Miller Mardi Gras Indian suit (2018)

(THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Laussat Society, 2021.0052)

Using bright red feathers, rhinestones, and beads of all sizes, Chief Howard Miller has created a piece of modern folk art rooted in centuries of New Orleans African American history and culture. Chief Miller is a member of the Creole Wild West, a tribe of Black Masking Indians whose oral tradition traces the group’s origins to the 1830s. Miller has masked for over 50 years, creating a unique suit each year. The beaded scenes on the vest and apron depict the Tramps, the early 20th-century predecessors of the Krewe of Zulu. Miller added a turquoise beaded necklace to the suit in recognition of the influence of various Native American tribes on African American culture in New Orleans.

Dorians King costume (1938)

(THNOC, 2005.0346)

United by shared business interests and a desire to promote trade and tourism, a wave of new krewes formed in New Orleans in the waning years of the Great Depression. Many did not parade, but hosted annual balls with kings, queens, captains, and other royalty selected from their membership. This king’s costume was worn in 1938 by William G. Zetzmann Sr. at the newly formed Krewe of Dorians’ Venetian-themed ball. Zetzmann was involved with many krewes from the 1930s through his death in 1962, including Hermes, Babylon, Moslem, and Virgilians. Dorians still exists today, hosting its traditional bal masqué each Carnival season.

Mystic Club Queen Regalia (1955)

(THNOC, 2014.0515.1.5, 2014.0515.1.6, and 2014.0515.1.7)

The Mystic Club was founded in 1922 and was known for its extravagant stage settings that depicted literary romances and historical events. It is also one of the few Krewes that selects a married woman for its queen, rather than a young debutante. Montine McDaniel Freeman wore this crown and scepter to a ball on February 19, 1955, with the theme “After the Battle of New Orleans.” The material is gilded metal with rhinestones.

The gown she wore is also lavishly decorated: the bodice’s geometric pattern is made with rhinestones and sequins. The most exotic and outstanding features—the capped sleeves with shoulder pieces of stiff wire—also are embellished. Crisscrossed beaded straps on the back are anchored with a large flower of rhinestones, matching the one in front.

“Old King Cole” float for Twelfth Night Revelers parade (1871)

(THNOC, 1975.117.5)

Mardi Gras as we know it began in New Orleans during the second half of the 19th century, when groups of white men gathered to form krewes, put on public parades, throw private balls, and tailor each celebration to a specific theme. The topics could be satirical, historical, fantastical, and exotic, and were often influenced by the popular literature and prevailing decorative movements of their day. The invitations, costumes, and float designs from the first few decades of New Orleans Mardi Gras krewes, often called “the Golden Age of Carnival,” are stunningly detailed and beautiful. This example from the Twelfth Night Revelers (or TNR) depicts the nursery rhyme “Old King Cole” and includes such charming details as a piping Pekinese pup. TNR is the second-oldest Carnival krewe, founded in 1870, and is credited for starting some of the most important Mardi Gras traditions to date. Examples include being the first to add debutantes as queens, maids, and other members to their royal court, as well as including political satire as an organizational theme. However, their most notable contribution was normalizing and instituting the practice of “throws,” after a masked Santa Claus figure in 1871 tossed an array of ornaments during the krewe’s parade.

“Hummingbird” float for Proteus parade (1974)

(THNOC, 2010.0029.25.2)

Founded in 1882, Proteus is one of only a handful of surviving old-line krewes. These groups were founded by and for white men. Many old-line krewes remained segregated until a 1991 law banned discrimination in social clubs. Some, including Proteus, halted their parading activities until 1995, when a federal circuit court removed the requirement to integrate by ruling that clubs “have a right of private association under the First Amendment."

Though their members were all male, many of the designers for the “old-line” krewes in their first century were female. One of the most prolific was Louis Andrews Fischer. She originally created “Hummingbird” for the 1973 Proteus parade, whose theme was “Tales Sea Shells Tell.” That parade was abruptly canceled due to rain, and Fischer’s design was recycled for the next year’s “Living Jewels” parade. Aside from her annual contributions to the Carnival season floats, Fischer was part of the creative community of the French Quarter, often hosting fellow artistic and literary friends, including Sherwood Anderson and William Faulkner, at her Pontalba apartment.

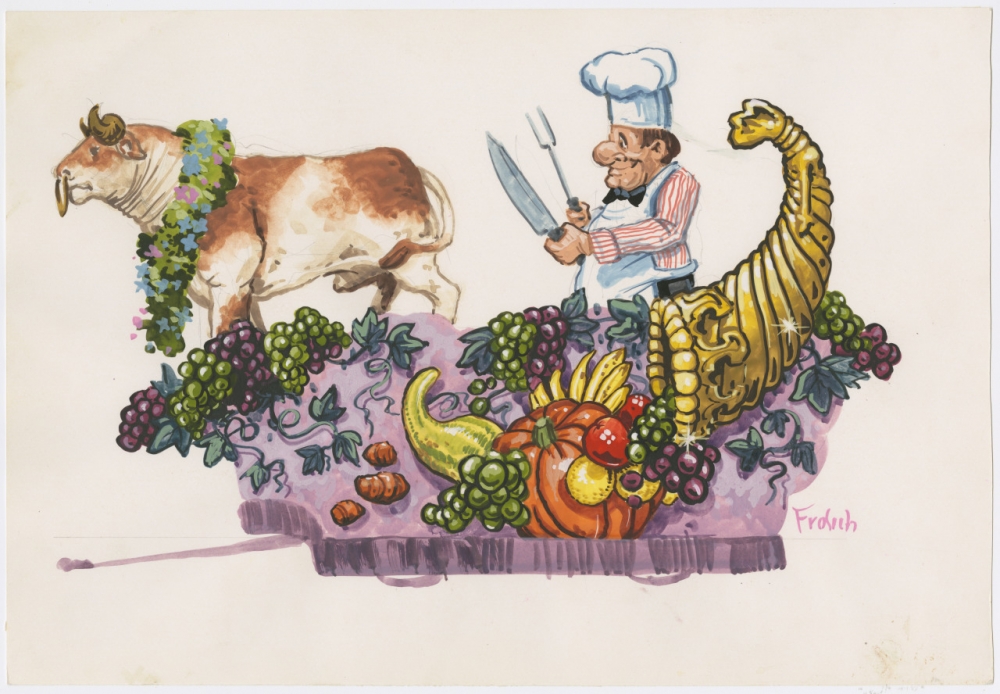

“Boeuf Gras” float for Rex parade, “Look to the Stars” (1977)

(THNOC, 1977.74.4)

The boeuf gras is a representation of the fatted ox, traditionally the last meat eaten before the beginning of Lent. Comus was the first parade to include a live boeuf gras in its 1867 procession, and other early Carnival parades often included an ox, either paraded on the street or hoisted on top of a float. The Rex parade last featured a live ox in 1901, and it wasn’t until 1959 that the group reintroduced the boeuf gras in papier-mâché form. Today the pure white garlanded boeuf graces the third float in Rex, following His Majesty’s Bandwagon.

Zulu coconut (1952)

(THNOC, 1977.86)

Formed in 1909 out of a loosely organized group called the Tramps and incorporated in 1916, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club is the oldest African American parading krewe. Zulu coconuts are one of, if not the, most coveted throw of Carnival. Zulu riders decorate and distribute a few hundred coconut shells apiece each year, after they are shaved, cleaned, and emptied of milk and meat. Today many riders create elaborate works of art, but in the past simple designs like this one were the norm. The exact history of coconuts as a Zulu throw is a little murky, but they may have been distributed as early as 1910, in one of the first Zulu parades. It seems the tradition of cleaning and decorating coconuts began in the 1940s. The King of Zulu in 1952 was William Boykins, who may have personally decorated this “King of 1952” coconut.