On Wednesday, August 25, The Historic New Orleans Collection hosted an online program on collections care, associated with the exhibition Pieces of History: Ten Years of Decorative Arts Fieldwork. A few days later, Category 4 Hurricane Ida hit Louisiana, tearing apart roofs, sending rain through windows, and knocking out power across the region. In the weeks that followed, temperatures reached three-digit highs and the humidity steadily increased while residents sweltered or evacuated. As a result, the contents of fridges and freezers spoiled, and mold bloomed in homes.

As residents return home and assess the damage, there have been many questions about how to care for the contents of their homes, especially their collections of antiques, photographs, and textiles. Heat, humidity, exterior force, and pests—all prevalent in the wake of a hurricane—are the primary threats to antiques. Here, we provide a few basic tips for triaging damage and caring for priceless personal treasures. In cases of extreme damage, always call a trained conservator rather than attempting to fix the problem yourself.

Documenting the damage

2021 Decorative Arts of the Gulf South (DAGS) fellows James Kelleher and Elizabeth Palms clean sideboard drawers they discovered in an attic.

Knowing what you have is always good object care, even more so after a natural disaster. Get out that handy Excel sheet or notebook list of your collection; if you don’t have one, this is a good time to start. Examine everything top to bottom and inside out, making notes of any breakage, soiling, or water damage. If you are considering filing an insurance claim, take photographs of damage before you start cleanup. A collection list will help you plan and organize your cleaning, repair, and storage needs.

Caring for wet photos

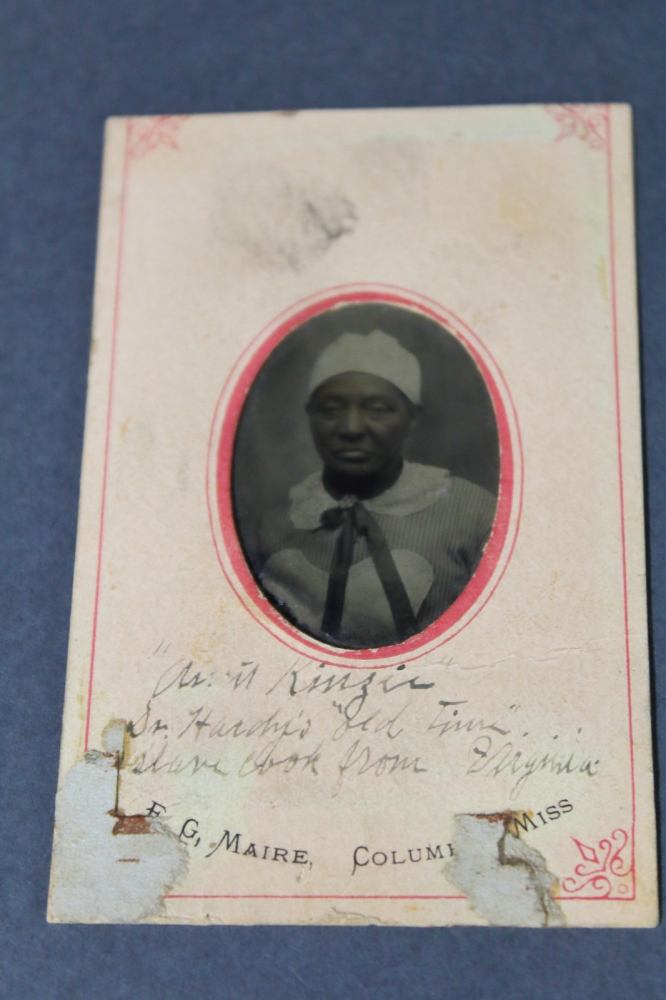

A photograph taken between 1855 and 1865 is labeled “Aunt Kinzi.” The image belongs to the Sykes family in Columbus, Mississippi. (Courtesy of the Decoroative Arts of the Gulf South project)

Lay wet photographs out to dry on a table lined with towels, in a well-ventilated room. According to Barbara Lemmen, senior photograph conservator at the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts, “If photographs are actively wet and adhere to each other, you can resubmerge them in water and attempt to pull them apart and allow them to air dry. If prints are dry, try to gently pull them apart.” Lemmen mentions not to stress the prints by pulling too hard. If the prints do not easily separate, call a photograph conservator. (For more from Lemmen, watch a recording of THNOC's 2020 program "Caring for Your Family Photographs.")

Caring for textiles

This quilt, created between 1860 and 1870, belonged to Bessie Winifred Whitfield of Corinth, Mississippi. (Courtesy of the Decoroative Arts of the Gulf South project)

If textiles got damp from water intrusion or being closed up in an extremely humid closet, the first step is to get them as dry as possible, as soon as possible. You can dry textiles by spreading them out and allowing ample air circulation around them. Be careful of leaving them in the sun too long, as sunlight might bleach the colors.

Textile conservator Howard Sutcliffe provided some further advice on how to deal with mold that may have grown on damp clothing or upholstery:

If the bloom only consists of less aggressive molds like mildew (white), then once they have been dried, clothes can be vacuumed using a vacuum cleaner with HEPA filter, and then either washed a couple of times or taken to a dry cleaner when they are back up and running. Molding surfaces in the closet can be sprayed using ethanol [ethyl alcohol] to kill the fruiting mold, then vacuumed once dry. I would then wipe the surface with ethanol again just to make sure. A bleach/water mix will also work for cleaning painted surfaces in closets. Masks should definitely be worn whenever dealing with mold. If there have been blooms of other types of mold, black mold in particular, then I would consult remediation experts, as you don’t want to mess with that. One of the main problems with the darker mold types is staining, which can be very difficult to deal with and reverse, as it essentially dyes the textile substrate. Obviously, for historic textiles, people should always consult their friendly local conservator!

Caring for ceramics, silver, and glass

This 1843 China service was created by three different Parisian manufacturers, Edouard Honoré, Jacob Petit, and François Rihouet. (Courtesy of the Decoroative Arts of the Gulf South project)

For dirty porcelain and fine china, wash gently and dry completely with a clean cloth before putting them away. More porous earthenwares, such as terra cotta and unglazed sculptures, should not be submerged in water or cleaned with soap, as these substances will be absorbed into the ceramic. If there are stains on these pieces, contact a conservator. Fine dishes should be stored on a sturdy, level surface. Try not to stack these items, as it can put pressure on the bottom pieces.

Dirty silver should also be washed with dish soap and thoroughly dried. High humidity can increase tarnish, so pieces may need to be polished as well. Washing and buffing with a clean cotton cloth will remove some slight tarnish. If a further polish is needed, use a silver polish with a low grit and do not use any polishing methods that require submerging or dipping the piece. Make sure that polish residue is thoroughly removed by using a cotton swab to clean out crevices and washing the silver after polishing.

Ideal silver storage is in a cool, dry, airtight place, packed so that pieces are not touching each other. You should wrap silver in silver cloth (which is usually the lining in silver chests), never in plastic or bound with rubber bands. In a museum setting, we also handle silver, and all metals, with gloves on to reduce transferring the moisture and sulfides in the oils of our hands to the objects. This is an extra step you can do in your home, but not necessary.

Looking at our historic windows after the storm, we’ve learned that glass is surprisingly strong. But anyone who has dropped a glass at the end of a night knows that glass is also fragile. Not only is glass unstable if dropped, but it can also suffer damage from moisture in the air. If stored in a humid environment, glass, especially lead crystal, can suffer from glass disease—when the salts in the chemical makeup of glass are leached from the material. This is called weeping. These salts are hygroscopic, meaning they attract more water as they leach out, worsening the problem and quickening the reaction. Weeping can eventually lead to crizzling, a series of small (sometimes microscopic) cracks, which can cause cloudiness and significantly weaken the glass. To put a stop to glass disease, wash and dry the glass and then store it in a stable environment with ventilation. Placing an open box of baking soda, or a couple of those “DO NOT EAT” silica packets from your last new pair of shoes, in the cabinet will help keep the humidity down. Always store glass the way it was intended to sit, on its foot, not turned upside down hanging from its foot or resting on its rim. This can cause stress within the form and can create a microenvironment within the enclosed bowl.

Caring for furniture

This sofa, created between 1820 and 1840, incorporates mahogany veneer, walnut, tulip poplar, pine, and iron. (Courtesy of the Decoroative Arts of the Gulf South project)

High humidity is a primary threat to any object, especially wooden ones. The swelling and warping that make your front door stick in hot weather can happen to furniture, too. After gently drying surfaces with a soft cloth, place a container of an absorbent substance like baking soda or DampRid near or inside furniture to draw out excess moisture. Use a vacuum with a brush attachment to remove dust and dirt. If cracks formed or veneer popped off due to expansion in the excess heat and humidity, collect any separated pieces and call a conservator.

If any mold bloomed on the surface of your furniture during its exposure to high humidity, wait until the surface is dry and then carefully remove spores with a brush, dry cloth, or vacuum with HEPA filter. Harsh products like bleach or Lysol are not as effective on mold and can damage furniture; use a cleaning solution of 30% water and 70% ethanol [ethyl alcohol] can help kill remaining active spores. Test the solution on a small inconspicuous area first. Always wear protective gear when dealing with mold. White mildew is easier to remove, while more toxic black mold may require professional remediation.

When to call a conservator

Gregory Landrey, Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library senior conservator emeritus of furniture (front), examines a ladder-back chair with 2012 DAGS fellows Caryne Eskridge, Lydia Blackmore, Maria Shevzov, and Whitney Stewart.

For advice on when to call in the experts, we called on our own resident expert, THNOC Conservation Coordinator Maclyn Hickey:

When something you treasure is damaged in a way that you cannot fix at home, like a torn letter, a painting with flaking or lifting paint, or a broken ceramic bowl or chair leg, and if you are willing to pay to have a professional repair it, you are ready to talk to a conservator.

You want to choose someone who specializes in the materials of which your treasure is made. Conservators are very specialized and over time develop experience and deep understanding of their chosen media. Using as example the above media, you would want a paper conservator, a paintings conservator, an objects conservator, and a furniture conservator, respectively.

Another consideration when choosing a conservator is whether or not they are local. If the conservator cannot be reached by car, you will probably have to ship your object to them, which is always risky. The person who packs your object may not know how to pack it safely, and the shipper may be rough with the package. When you can, go with a local conservator. And be willing to talk to two or three conservators about your project; you will be surprised how much you can learn just by listening and asking questions.

Useful resources:

National Heritage Responders, “Mold in Collections”

American Institute for Conservation, “Find a Professional”

The Historic New Orleans Collection, "Caring for Your Family Photographs"