Lining two sides of Jackson Square are the resplendent brick row houses named the Pontalba Buildings, which were completed in the early 1850s and remain French Quarter landmarks. The Upper Pontalba Building—now owned by the City of New Orleans—is on St. Peter Street, and the Lower Pontalba Building, owned by the state, is on St. Ann Street.

The story of these buildings begins with Spanish colonial official Don Andrés Almonester y Roxas. Almonester became one of the richest men in Louisiana largely through acquisitions of land and enslaved people, and he was heralded for his sizable contributions to civic projects. After the fire of 1788, he funded the reconstruction of St. Louis Cathedral as well as the construction of the Cabildo and the Presbytère, all of which bordered the Plaza de Armas, as Jackson Square was known during the Spanish period.

Among Almonester’s many properties were two tracts of land perpendicular to the cathedral. Eventually these properties and his immense fortune descended to his heir and daughter, Micaëla Almonester, Baroness de Pontalba.

Micaëla Almonester, Baroness de Pontalba, led the construction of two massive buildings lining Jackson Square starting in 1849. (THNOC, 1974.25.27.358)

The baroness spent her early adulthood in France after marrying a French aristocrat, an arranged union marked by tumult that included her father-in-law shooting her four times at close range and then killing himself. After separating from her husband, the baroness returned to her childhood home of New Orleans.

Accompanying her to New Orleans was the Baroness's youngest son Gaston. During their three years in the city, Gaston captured the architecture and activity in the city in vivid detail through sketches and watercolors. These included views of his mother's buildings of row houses as they were being constructed. Recently discovered in France, the works were loaned to THNOC by the Pontalba family for the 2019 exhibition The New Orleans Drawings of Gaston de Pontalba, 1848–1851.

Gaston de Pontalba, the baroness’s son, made this drawing of his mother’s building on the upper side of Jackson Square. (Courtesy of the Baron de Pontalba)

The baroness returned home with a newfound appreciation for Parisian architecture and decided to tear down the existing buildings on the properties facing the square and replace them with the structures that bear the Pontalba name today. She hired esteemed architect James Gallier to make preliminary sketches in 1849, but it appears that they had a falling out, as the building contract that survives uses Gallier’s work but has his name scratched out and “Nul.” written by it. The contract was given to general contractor Samuel Stewart, while another prominent architect, Henry Howard, was retained. Howard, too, left the job after evidently clashing with the baroness. She monitored the endeavor vigilantly, and was even reported to have donned men’s work clothes and scaled the ladders at the construction site.

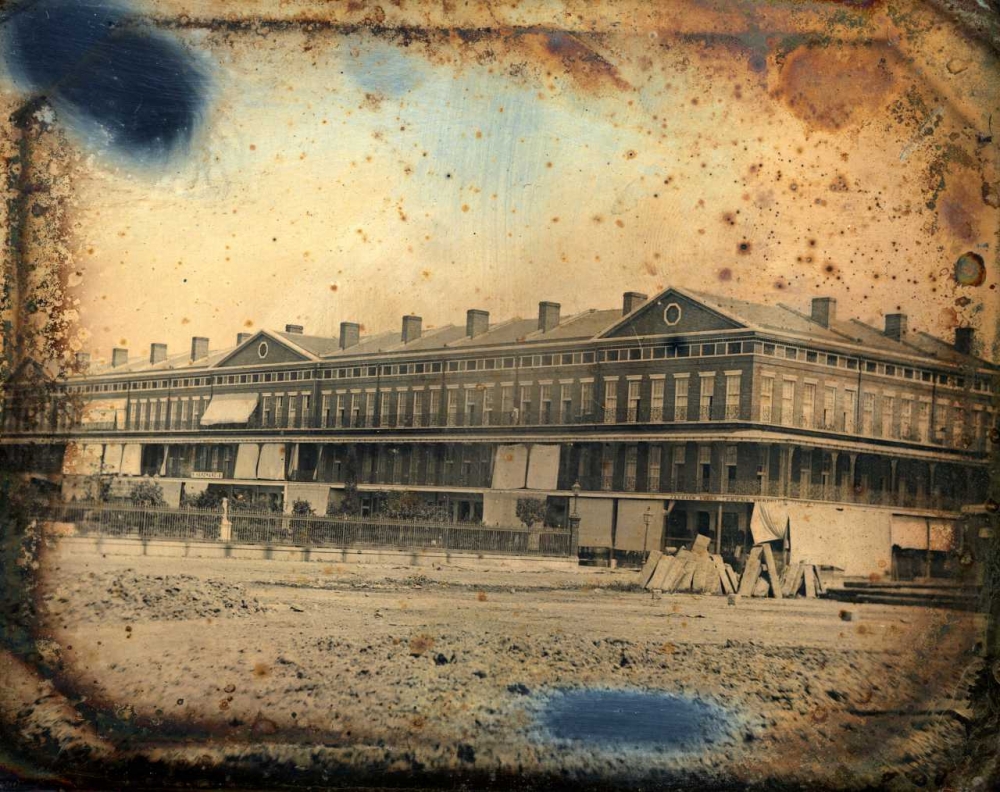

The Lower Pontalba building, along St. Ann Street, is shown around the time of its construction between 1848 and 1851. (Courtesy of the Baron de Pontalba)

Without an experienced architect the project endured delays and cost overruns, which the baroness tried to avoid paying. After completing his work, Stewart sued her to recoup his expenses. Despite the chaotic process, when the Upper and Lower Pontalba Buildings opened, newspapers extolled their beauty and civic importance. Their cast-iron galleries are believed to be the first installed in New Orleans.

A modern image by Jan and Robert Brantley shows the stately Upper Pontalba building along Jackson Square. The buildings remain among New Orleans’s most recognizable landmarks. (©Robert Brantley; THNOC, gift of Jan White Brantley and Robert S. Brantley, 2015.0415.33)

The baroness’s work spurred other developments, including renovations to the cathedral and the Cabildo. In 1851 the city began erecting the square’s iron fence and laying the flagstones in the sidewalk—features that remain today—and renamed the area Jackson Square. That year, the baroness left New Orleans for the final time, retiring to France to reunite with her husband. More than a century and a half later, her most important legacy in this city endures.

This story originally appeared in the Historically Speaking column of the New Orleans Advocate.