Interpretation Assistant Kurt Owens gives us a brief history of Carnival throws and a first-hand account of decorating and catching the most prized throw of Mardi Gras, the Zulu coconut.

Mardi Gras Day, 1992, St. Charles Avenue:

Again and again I pushed forward with outstretched arms, pleading dutifully, “Throw me a coconut, Mister!” to no avail. Then, from the second level of a double-decker float, I noticed a Zulu member lowering a coconut in a plastic bag, suspended from a simple piece of twine. My pulse raced; my eyes were fixed. I raised my hand, the treasure softly landed in my grip, and the rider dropped the twine. I think I recall screaming. I wrapped the twine around my neck and wore the coconut as if it were a Tiffany lavalier the remainder of the morning.

The elation and thrill of getting my first Zulu coconut is one of my most-loved Mardi Gras memories, one that gives me a flutter of excitement even today. Some people might ask: why in the world would a grown man care so much about decorated coconut?

When did the throwing start?

A float design for the Twelfth Night Revelers’ 1871 procession. Following the parade, Santa Claus distributed gifts from a bag, marking the first appearance of Mardi Gras “throws” in the city. (THNOC, 1975.117.5)

The tradition of “throwing” trinkets and treats to a mass of revelers predates Carnival itself. The ancient Romans distributed whips made of goat hide—and playful whippings—to the frolicking crowds at the conclusion of Lupercalia, the early forerunner to the Carnival celebration we know today. These annual rites of purification and fertility were associated with the vernal equinox that marked the return of the sun. In medieval France, the fête de la quémande saw groups of peasants emerging from the dark winter, donning miters and pointed hats to mock the wealthy classes, and begging and dancing for items to eat. That tradition continues today with the Cajun courir de Mardi Gras.

In early-19th-century New Orleans, processions of ladies en route to Carnival balls were said to have tossed sweets and bonbons, as well as provocative smiles, to gentlemen along the route. Bands of youths would throw flour (and, later, nastier substances, such as rotten fruit, plaster pellets, urine, and caustic lime) at revelers on Fat Tuesday. One newspaper in the 1840s reported on Ash Wednesday that the streets looked as if snow had fallen.

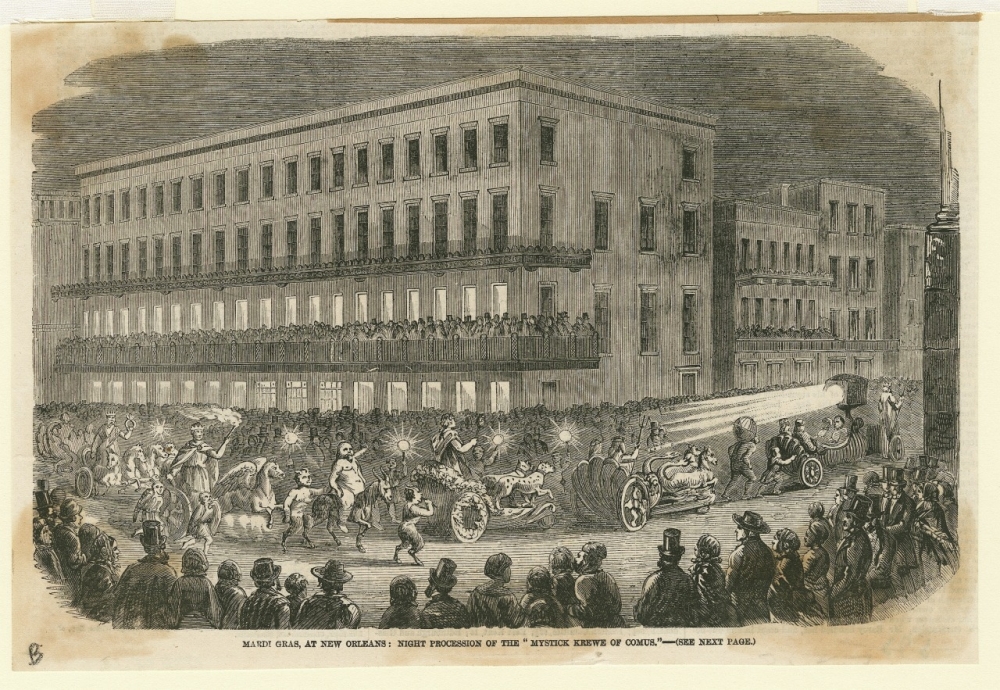

An 1858 engraving depicts the Mystick Krewe of Comus, the first organized parading organization in the city. (THNOC, 1974.25.19.1)

The first reports of items being thrown as part of the official parades we know today came in the early 1870s with the second procession of the Twelfth Night Revelers, according to Carnival historian Errol Laborde. Following their “Mother Goose’s Tea Party”–themed parade, a costumed Santa distributed gifts from his bag.

Rex: the bringer of beads and doubloons

Rex’s float processes down Canal Street in the 1950s. Rex was the first parade to introduce "throws" as we know them today. (THNOC, gift of Stephen Scalia, 2012.0172.103)

In the early 20th century, the Rex Organization began the tradition of tossing throws to the crowd from each float. Strings of hand-strung glass beads quickly became the desired souvenir. According to a master’s thesis written by the late Lissa Capo, who was THNOC’s in-house expert on Carnival throws, the earliest surviving examples are Japanese mercury glass beads, made during WWII. Czechoslovakian crystals were in vogue next, through the 1960s, when they were superseded by hand-strung plastic necklaces. With the arrival of plastic beads molded directly onto polyester strings, the throws became bigger, longer, showier, and more customizable to each krewe. Abundant strings of oversized beads became the new gold standard, beloved by viewers. And the krewes responded, throwing more and more—and more.

A rider in Hermes tosses a cup into the crowd in 1998. The introduction of cups marked a decline in doubloons.(THNOC, gift of Mitchel Osborne, 2007.0001.114)

Anodized aluminum coins, known as doubloons, debuted with Rex in 1960, surprising the crowds and becoming a coveted commodity. Many collectors remember the method of securing a doubloon thrown from a float: quickly covering the doubloon with one’s foot and then retrieving the coin.

According to Judy Walker of the Times-Picayune, the introduction of plastic cups in the early 1980s marked the decline of interest in doubloons. More recently, all things battery-powered have become all the rage, with each year bringing new variations—blinking necklaces, light-up medallions, and flashing rings. Today, the parade route glows with the lights after the last float has passed.

Watch your head and click your heels!

The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club was the first to develop a signature throw, the coconut, which is still prized today. (THNOC, gift of Mitchel Osborne, 2007.0001.242)

The early 20th century marked the arrival of painted walnuts and, later, painted coconuts from the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club. Today the painted, glittered, and feathered coconuts are passionately sought—something of a holy grail for even experienced parade-goers.

The Zulu coconut influenced other krewes and walking clubs to create their own signature throws. In 2001, a member in the Krewe of Muses—using the Zulu coconut as inspiration—introduced their tradition of presenting glittered, decorated high-heeled shoes as the prized throw of their parade. Each one is intended to be a unique work of art for the lucky recipient. Other krewes have thrown bedazzled oyster shells, brassieres, wine corks, goblets, grails, eyeglasses, toilet scrubbers, eggs, and more. There seems to be little a Carnival-loving New Orleanian won’t encrust with glitter! And, on the receiving end, there’s little a dedicated parade-goer won’t do to secure one of these treasures—screaming, dancing, and making a general fool of one’s self. Such is the magic of the season.

Owens is shown decorating a slew of coconuts for a friend who rides in Zulu, in preparation for Mardi Gras 2018. (Image courtesy of Kurt Owens)

In recent years, concern over plastic waste has generated discussion about the future of Carnival throws. According to a 2018 article in the Times-Picayune, Carnival produces an average of 900 tons of waste—much of it beads and throws—each year. Not only do the throws quickly become trash—either when abandoned on the parade route or thrown out by the recipient after Mardi Gras—but they also aggravate street flooding, with a proportion of them clogging the municipal catch basins designed to retain runoff. In March 2018, New Orleans learned that over 46 tons of discarded beads had been removed from drains between Poydras Street and Lee Circle alone. In the fall of 2018, the Urban Conservancy hosted a symposium on Carnival throws and sustainability. Panelists introduced ecologically friendly throws, such as paper beads crafted from magazine pages by Ugandan women, recyclable styrene beads, and biodegradable glitter.

This footage from 1968 shows debris from Mardi Gras being swept up on Ash Wednesday. Mounting waste and clogged catch basins have prompted residents to reconsider the role of throws in Mardi Gras. (The Jules Cahn Collection at THNOC, 2000.78.4.34)

My Zulu coconut, adorned with a face and a large “Z,” remains a cherished memento, and I need never beg for one again. These days, THNOC Interpretation Assistant Malinda Blevins and I decorate coconuts for a friend who rides in Zulu, which means we’re guaranteed one.

Cover image: Hermes parade; February 24, 1995; photograph by Mitchel L. Osborne; THNOC, gift of Mitchel L. Osborne, 2007.0001.95

Cover image: Hermes parade; February 24, 1995; photograph by Mitchel L. Osborne; THNOC, gift of Mitchel L. Osborne, 2007.0001.95