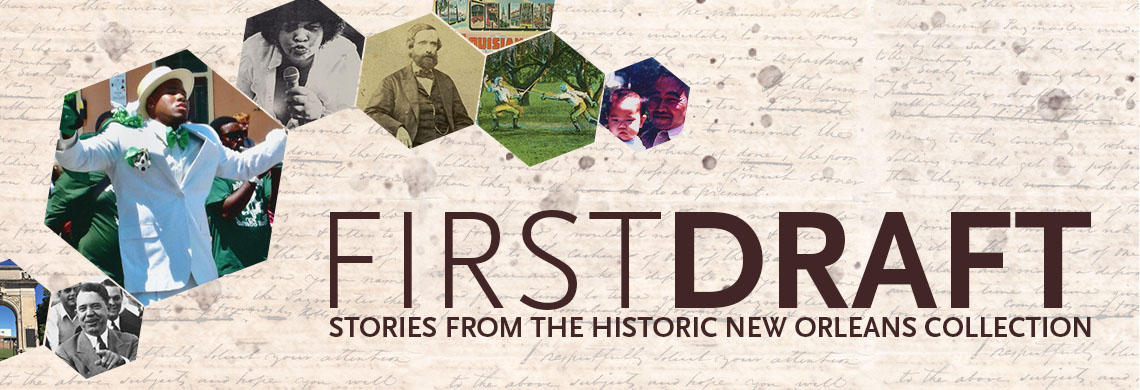

The 1951 film of Tennessee Williams’s New Orleans-set A Streetcar Named Desire won multiple Academy Awards and is considered a landmark of American cinema. To prepare for the August 24, 2020, #NolaMovieNight group re-watch of the film, First Draft returned to local dialect coach and acting teacher Francine Segal for insight into the film’s accents (always of interest to New Orleanians) and acting styles.

To set the stage (as it were) for the August 24 #NolaMovieNight group screening of the 1951 film version of A Streetcar Named Desire, First Draft reached out to two Tennessee Williams Annual Review principals for insight into the publication and some thoughts on the film’s cultural impact.

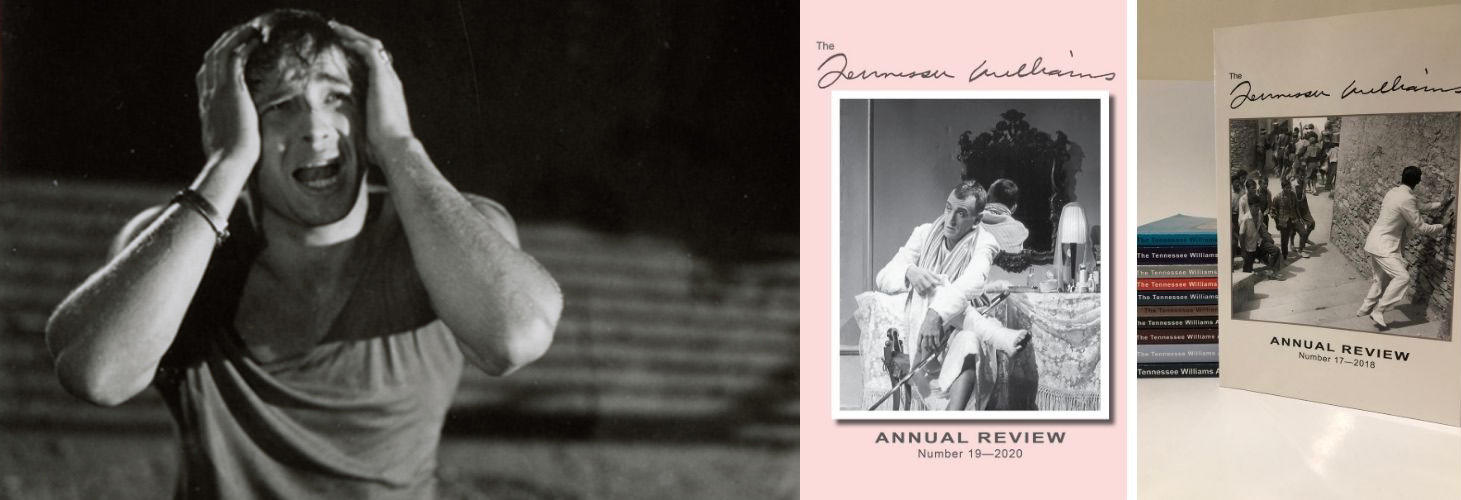

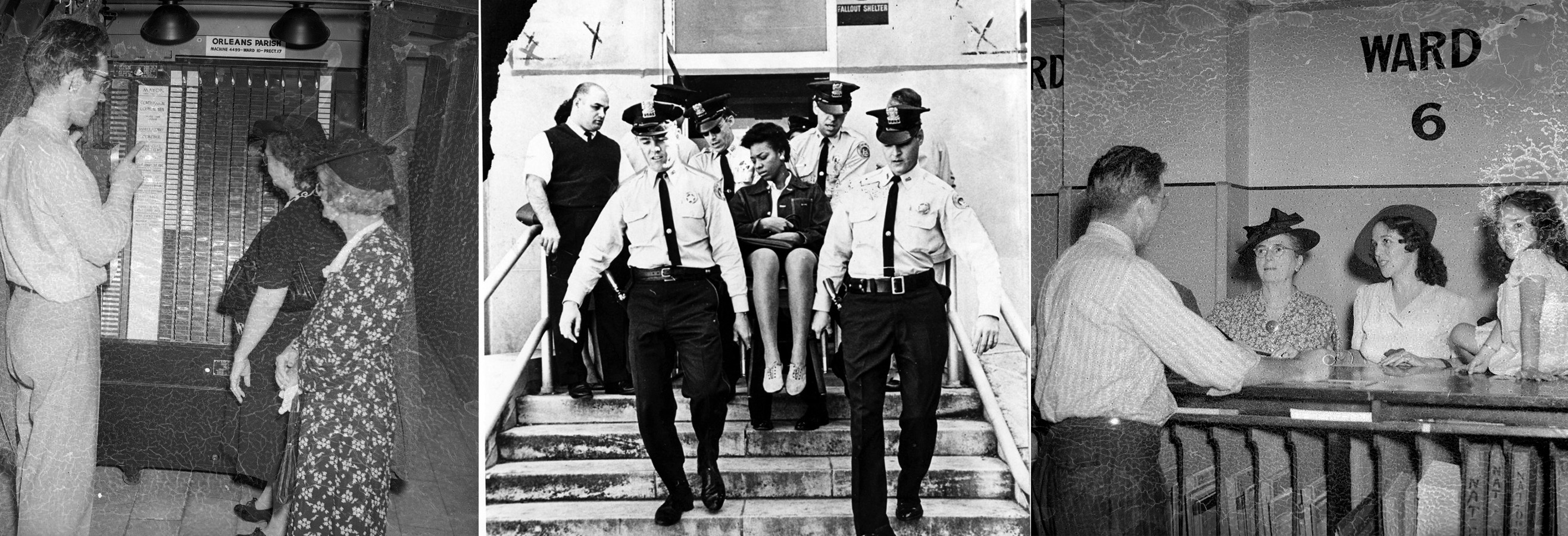

Often, the story of women’s suffrage ends at the ratification of the 19th Amendment. Yet, for many women in the South, the fight did not end there.

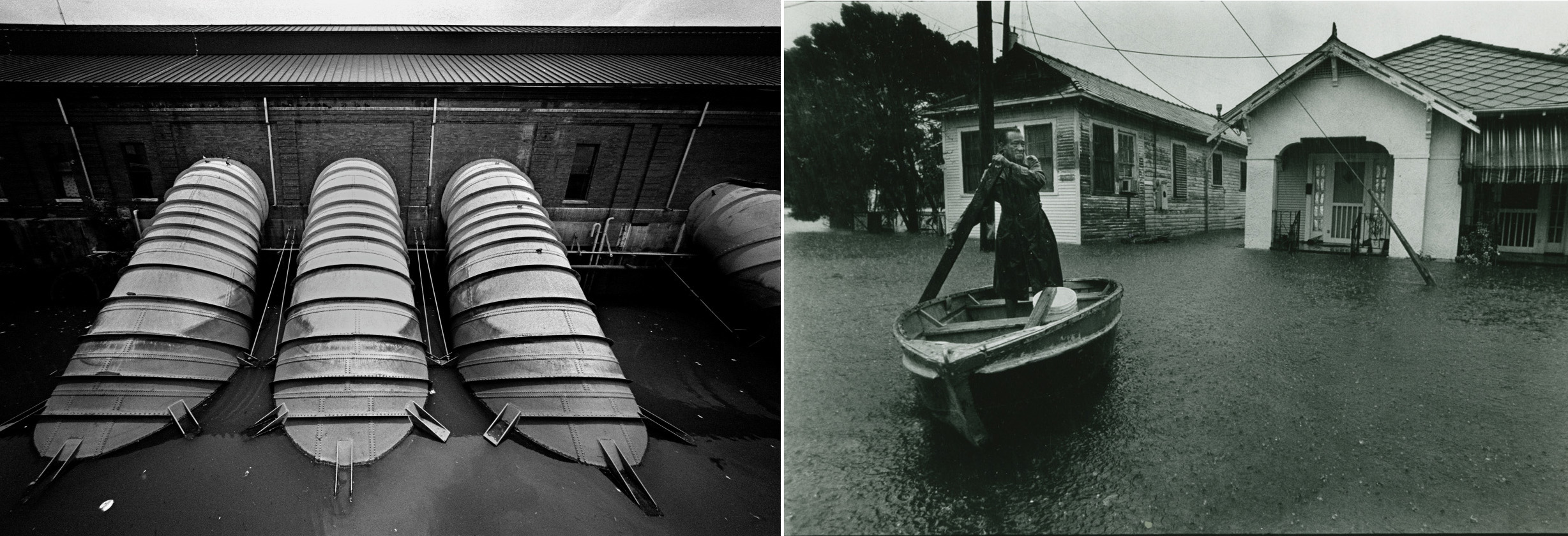

A new pumping system in the early 20th century improved New Orleans's drainage crisis, decreased disease rates, increased the quality of the water supply, and drove economic growth throughout the city. These improvements, however, came at a mighty cost.

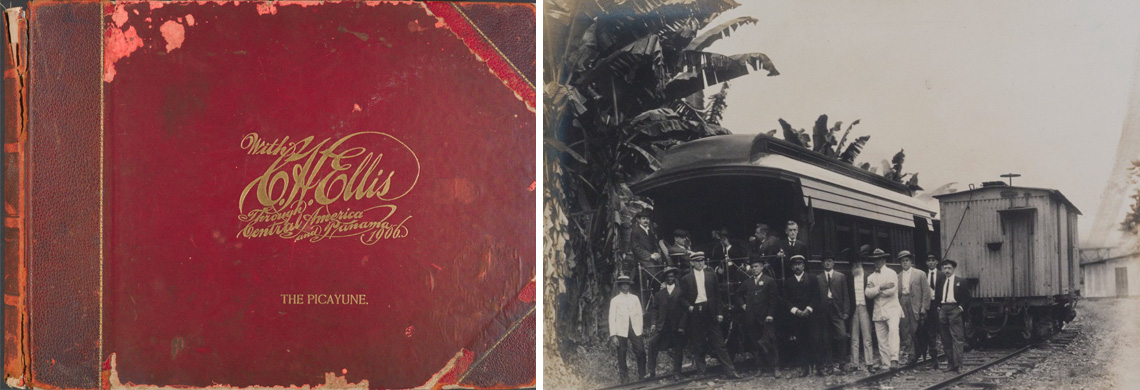

A large photograph album bound in red leather documents a 1906 “quarantine tour” of Central America sponsored by the United Fruit Company during the final outbreak of yellow fever in New Orleans. The book is a fascinating example of the tremendous influence of the banana-import business in early 20th-century New Orleans and the efforts by one company to skirt quarantine regulations.

When she died in June 2019 at age 96, Leah Chase was celebrated as a New Orleans legend, icon, and inspiration. During research for 2009’s animated The Princess and Frog, directors Ron Clements and John Musker called on Chase’s life story and culinary renown—a journey from French Quarter waitress to James Beard Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award recipient—as inspiration for the character of Tiana, Disney’s first African American princess.

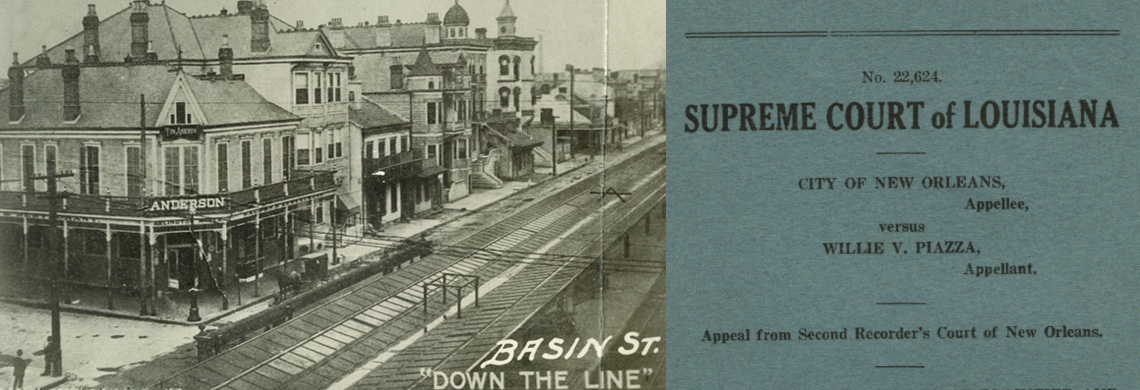

Storyville's blue books marketed a fantasy of the red-light district to a white male audience, offering a fascinating, yet limited, window into a demimonde during the rise of consumerism.

When the City of New Orleans passed an ordinance to remove black prostitutes from Storyville, Willie Piazza fought back. Her challenge to segregation was an early, though fleeting, victory against Jim Crow.

Casino Royale became Stormy’s Casino Royale in 1948, named for (but not owned by) its star act, Stacy “Stormy” Lawrence. The club became known for featuring some of the most outlandish acts on Bourbon Street.

Curator/Historian Eric Seiferth takes us through the music scene on Bourbon Street in the 1950s.