With marriage and family aspirations taking the fore, the Boswell Sisters disbanded in 1936. Though their time in the limelight was short-lived, the Boswells influenced close-harmony groups and solo artists for decades. The Andrews Sisters, remembered as the preeminent female vocal group of the 1940s, openly admitted to copying the Boswell sound, and Ella Fitzgerald cited Connie Boswell as one of her biggest influences.

As Martha and Vet settled down to raise their families, Connie carried on as a solo act. She married longtime manager Harry Leedy and maintained her celebrity through the 1940s and ’50s with such hits as “Moonlight Mood” (1942) and “If I Give My Heart to You” (1954). That her career succeeded for so long despite the many difficulties she faced as a disabled woman is an added testament to her talent and drive.

Vet Boswell’s daughter, Chica, loved to hear her mother talk about the sisters’ glory years and, later in life, started documenting their career and collecting ephemera from other Boswell family members. In 1998, along with her daughter, Kyla Titus, as well as a team of musicologists, Chica established the Boswell Museum of Music, located in upstate New York, to keep the legacy of the Boswell Sisters alive. After Chica passed away in 2010, Kyla and the board of the Boswell Museum—who had long thought that the contents of the museum should eventually reside in New Orleans, the sisters’ home and source of inspiration—selected The Historic New Orleans Collection to be the trusted caretaker of the Boswells’ priceless legacy. Shout, Sister, Shout! The Boswell Sisters of New Orleans celebrates this important addition to the city’s cultural heritage.

Vet Boswell’s banjo

n.d.

by Beltone, manufacturer

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of the Boswell Museum of Music, 2011.0315.127

Vet, the youngest Boswell sister, was named, oddly, for the Helvetia Milk Condensing Company, because of the milk she was bottle fed as an infant. In addition to being a talented vocalist, she was also a “terrific tap dancer,” as stated by Connie, and multi-instrumentalist who studied both the violin and banjo. Generally acknowledged as the most reserved of the sisters, she was far from timid and, according to one news article, was reputed to “make the funniest faces of anyone around the CBS studios.”

Clydie Boswell’s violin

before 1918

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of the Boswell Museum of Music, 2011.0315.128

At fourteen, Clydie Boswell moved with his family from Kansas City, Missouri, to Shawnee, Kansas, and Birmingham, Alabama, before settling in New Orleans. He joined his sisters in receiving a classical-music education from professor Otto Finck, studying the violin. Though classically trained, the jazz and blues rhythms of his adopted city grabbed Clydie; he went on to study with vaudeville orchestra leader Joseph Fulco and formed friendships with cutting-edge jazz musicians such as Emmett Louis Hardy. By eighteen Clydie had found work as an auto mechanic with the Universal Motor Company. Like many other young men of his generation, he heard the call to serve in the First World War and enlisted in the army, but, sadly, contracted influenza shortly after his enlistment and died in an army hospital facility on October 22, 1918.

Connie Boswell’s wheelchair

n.d.

by Knauth Brothers, manufacturer

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of the Boswell Museum of Music, 2011.0315.158

The source of Connie’s disability, which started when she was three years old, has never been clearly confirmed. The impairment is often attributed to a childhood bout with polio. According to family lore, the true cause was a go-cart accident, but that story could have been fabricated by the fiercely protective Meldania Boswell, Connie’s mother, to spare her daughter the stigma of the disease. In interviews over the years, Connie cited both stories. Meldania devised a physical-therapy regimen that successfully restored some of Connie’s mobility during her adolescence. At home Connie was never treated any differently, and when the Boswells’ career began taking off, Vet and Martha helped hide Connie’s physical limitations from the public. Connie would frequently perform while seated at the piano, next to Martha, with Vet standing close behind. Later in her career, Connie used a custom-designed wheeled stool, concealed by her skirts, which allowed her to take the stage and appear to be standing. This wheelchair, believed to have been used by Connie as early as 1931, was discovered in the former home of Martha Boswell near Peekskill, New York.

Press book of Harry Leedy, manager of the Boswell Sisters

1932; booklet, press clippings

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of the Boswell Museum of Music, 2011.0315.48

On a visit to California in 1929, the Boswells met a man who would make an indelible mark on their career and personal lives. Harry Leedy was employed at the San Francisco hotel where the sisters were staying, and a friendship was formed. They again met in Los Angeles in October 1930, and the sisters took him on as their manager. He was instrumental in negotiating the 1931 contract with NBC that brought the sisters to New York City. Leedy and Connie formed a deeper relationship, and the couple wed in 1935. Leedy continued working as her manager throughout her solo career, and their love endured until Leedy’s death, in 1975.

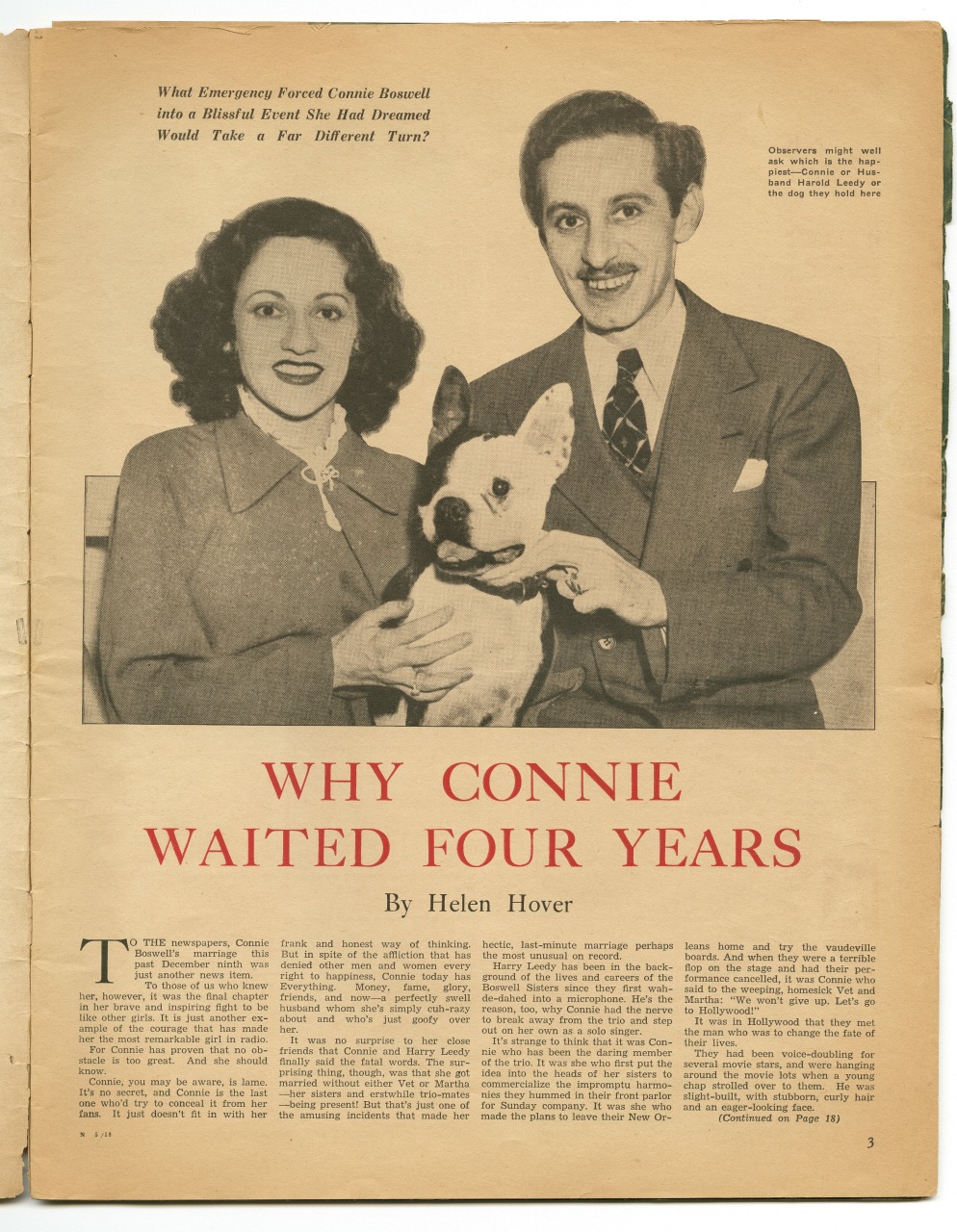

Connie Boswell, Harry Leedy, and dog Buzz from Radio Guide magazine

February 1936; photoprint

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of the Boswell Museum of Music, 2011.0315.156

In February 1936 the Boswell Sisters made what would be their final recordings as a trio, “Let Yourself Go” and “I’m Putting All My Eggs in One Basket,” as Martha and Vet settled down to raise families and Connie embarked on a solo career. Having taken many independent jobs during her work with the group, Connie was used to performing without her sisters, but she struggled to craft a new public identity as a soloist. She found herself performing in smaller venues and nightclubs, many of which were not readily equipped to accommodate her wheelchair. Connie recorded with both Bing Crosby and Bob Crosby and his Bob Cats, and made regular appearances on radio and television. At the outset of the Second World War, when her fellow entertainers began to depart on USO tours, Connie was forced to remain stateside—her disability presented too great of a logistical hurdle for organizers. Still, she participated in the war effort on the home front, visiting veteran’s hospitals.

“The Lone Boswell Carries On”

from the Louisville Times

January 11, 1936; newspaper clipping

by Hilda Cole, writer; Burrelle’s Press Clipping Bureau, compiler

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of the Boswell Museum of Music, 2011.0315.153

By January 1936 the Boswell Sisters’ career as a trio was coming to an end. Connie and Vet had married in 1935, Vet to oilman and journalist John Paul Jones, in July, and Connie to manager Harry Leedy, in December. Both Connie and Vet opted to withhold public knowledge of their marriages for several months. By the time this article was published, Martha had married the “New York man” referenced in the story, former Royal Air Force aviator and Decca executive Major George Lloyd.