So much of New Orleans’s musical culture rests on its diversity, of styles, practitioners, and influences. The music of the African diaspora is a big part of this story.

It was a hot June day in 1969, when for the first time, black and white kids dove into the Audubon Park swimming pool together, marking a symbolic victory for the civil rights movement in New Orleans.

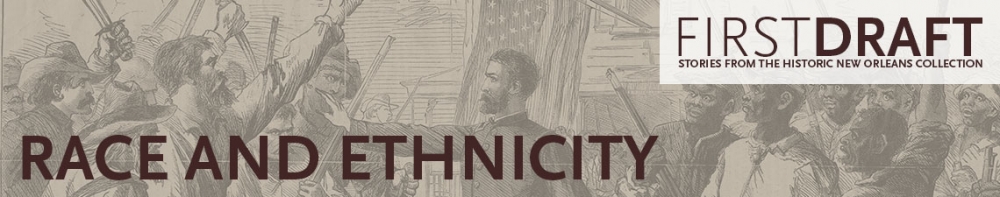

Through letters, photographs, and scrapbooks, we learn about the business prospects, educational opportunities, poverty, war, and illnesses that immigrants to the city encountered in the mid-19th century

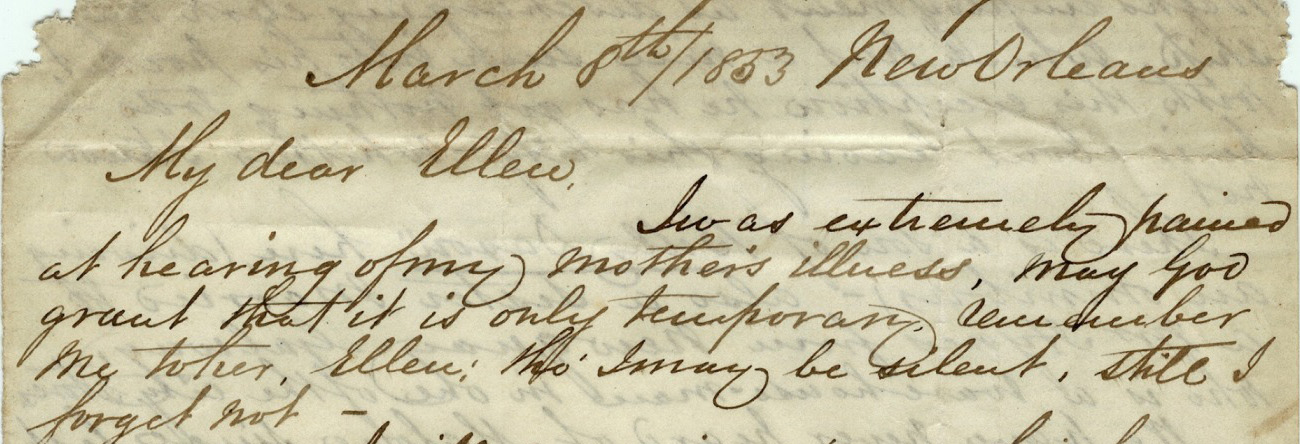

In 1866, at a time when horse racing was arguably the most popular sport in America, the New Orleans Times hailed Abe Hawkins as “probably the best rider on the continent.” Once enslaved on a Louisiana plantation, Hawkins, in just a few years, achieved fame and fortune, and changed the sport forever.

The idea of benevolent slaveholders treating their enslaved workers like family has been persistent since the antebellum period, and, piece by piece, the ads in “Lost Friends” help to set the story straight.

On a sweltering July day, 19-year-old New Orleans native Chasity Hunter admits that she’s considered leaving her hometown. When asked where she’d go, she says, with a laugh, Massachusetts, “because it’s cold.” New Orleans’s tumultuous relationship with Mother Nature has certainly shaped Hunter’s feelings about her city—but it also set her on a path of discovery that changed her life.