The second contest between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson was one of the nastiest, most vituperative political races in American history. Confronted with the popularity of the Hero of New Orleans, Adams’s supporters attempted to tarnish Jackson’s military reputation by turning it against him. They criticized the general’s declaration of martial law in New Orleans in 1814–15 and focused attention on another wartime incident concerning the court-martial of six Tennessee militiamen in Mobile for mutiny in December 1814. Jackson had upheld their death sentence from New Orleans, hoping this severe example would prevent mass desertions and preserve the security of the region. The executions were carried out on February 21, 1815.

The six dead men were eulogized in 1828 in a series of so-called coffin broadsides from pro-Adams publishers who accused Jackson of being a murderer. These episodes and others from the First Seminole War and Jackson’s civilian life were used to paint the Hero of New Orleans as a tyrannical “Military Chieftain” who could not be trusted with the power of the presidency.

The 1828 election fundamentally hinged on the personalities and pasts of both candidates, rather than their political philosophies. In the end, Jackson’s huge popularity in the South and West could not be denied, and he won the election in a landslide, carrying all but a handful of New England states. His jubilant supporters decorated their homes and places of business with souvenir objects—some manufactured in England—commemorating Jackson as “the People’s President.”

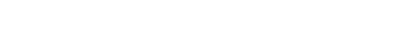

Jackson at New Orleans. Adams at Ghent.

1828; letterpress broadside with woodcut

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2001-68-L.17

This pro-Jackson broadside from the 1828 presidential election contrasts the heroic general's fitness for office with Adams's dubious use of treasury funds and his unpatriotic criticism of US armed forces while on diplomatic duty abroad.

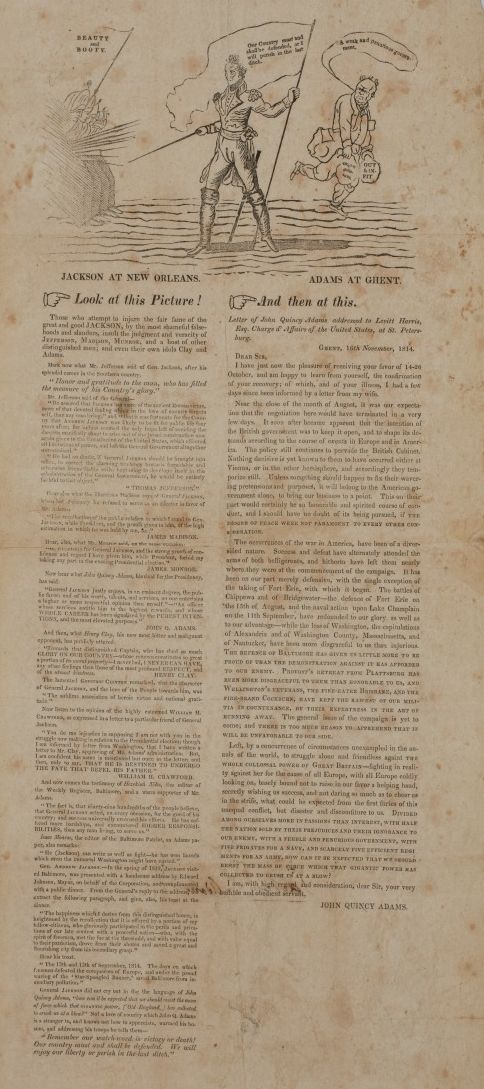

Is Jackson Fit to be President?—Read What Follows, and Judge Ye!

1828; letterpress handbill

by the Kentucky Reporter, publisher

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2001-68-L.31

A pro-Adams handbill highlights an 1813 brawl between Andrew Jackson and Thomas Hart Benton and others in Nashville, asking if those opposed to "the principal actor in this bloody outrage" would be safe if Jackson was elected president and accusing him of planning "military rule."

Andrew Jackson copper luster pitcher

ca. 1828; earthenware with lusterware decoration and transfer print

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2014.0249.1

Household objects commemorating Jackson as a presidential candidate became enormously popular in the 1820s. This pitcher was likely manufactured in Staffordshire, England. The portrait appears to be based on an 1824 engraving by James Barton Longacre (1794–1869) or a similar 1825 example by Peter Maverick (1780–1831); both engravings were in turn derived from an original 1824 miniature watercolor by Joseph Wood (1778–1830), now lost.

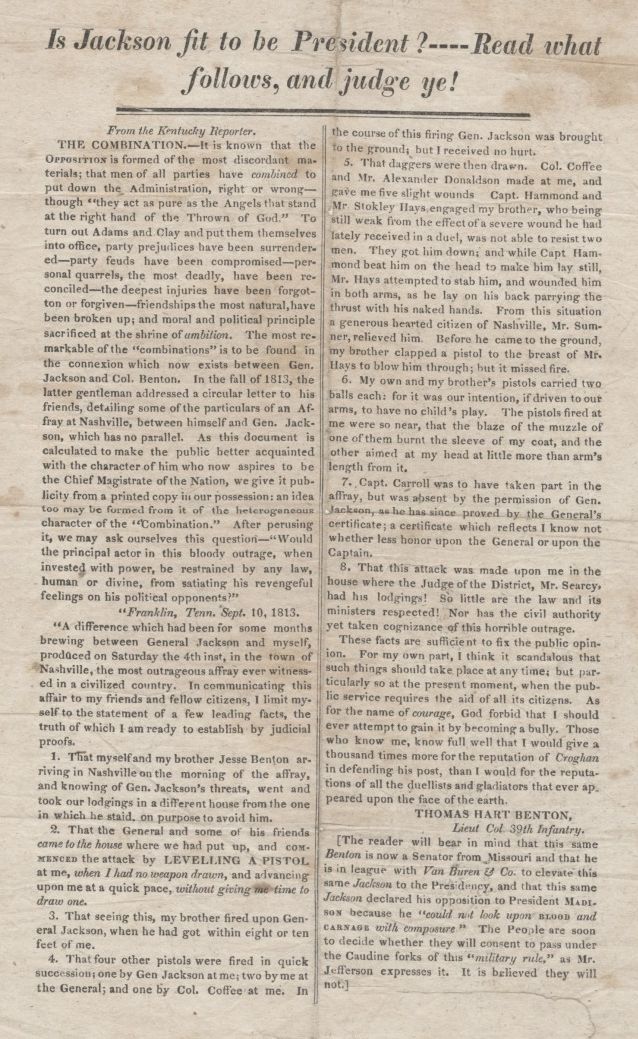

Monumental Inscriptions!

1828; letterpress broadside with woodcut

by John Binns, publisher

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2001-68-L.18

John Binns (1772–1860), an Irish-born Philadelphia journalist and publisher, opposed Jackson's presidential candidacy in 1824 and again in 1828. He produced the first of the so-called coffin broadsides, based on an incident from Jackson's wartime oversight of troops, to sway voters and undercut Jackson's formidable reputation as a military hero.

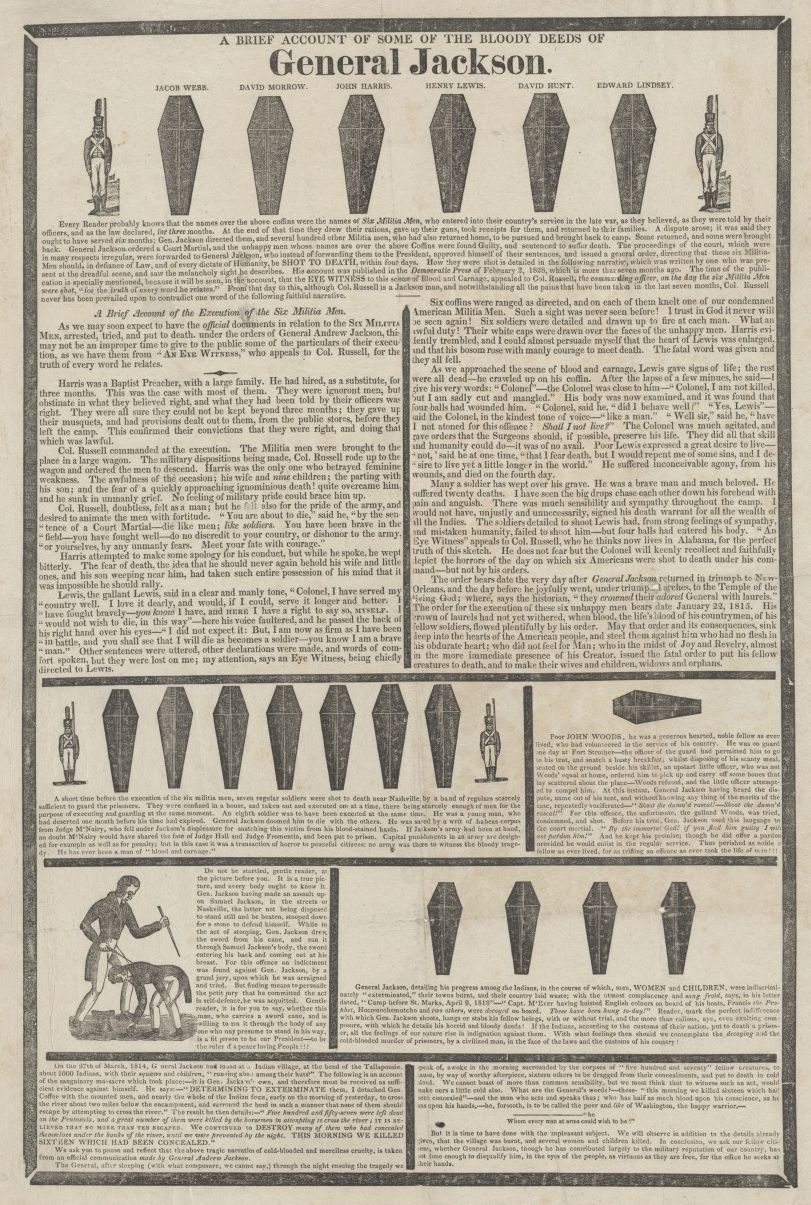

A Brief Account of Some of the Bloody Deeds of General Jackson

1828; letterpress broadside with woodcut

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2001-68-L.28

The coffin broadsides produced by Jackson's opponents in 1828 eulogized six Tennessee militiamen found guilty of desertion from their post in Mobile in the waning days of the War of 1812. Jackson upheld their death sentence from New Orleans. This example gives an eyewitness account of the executions. An inset woodcut shows Jackson attacking another man with a cane.

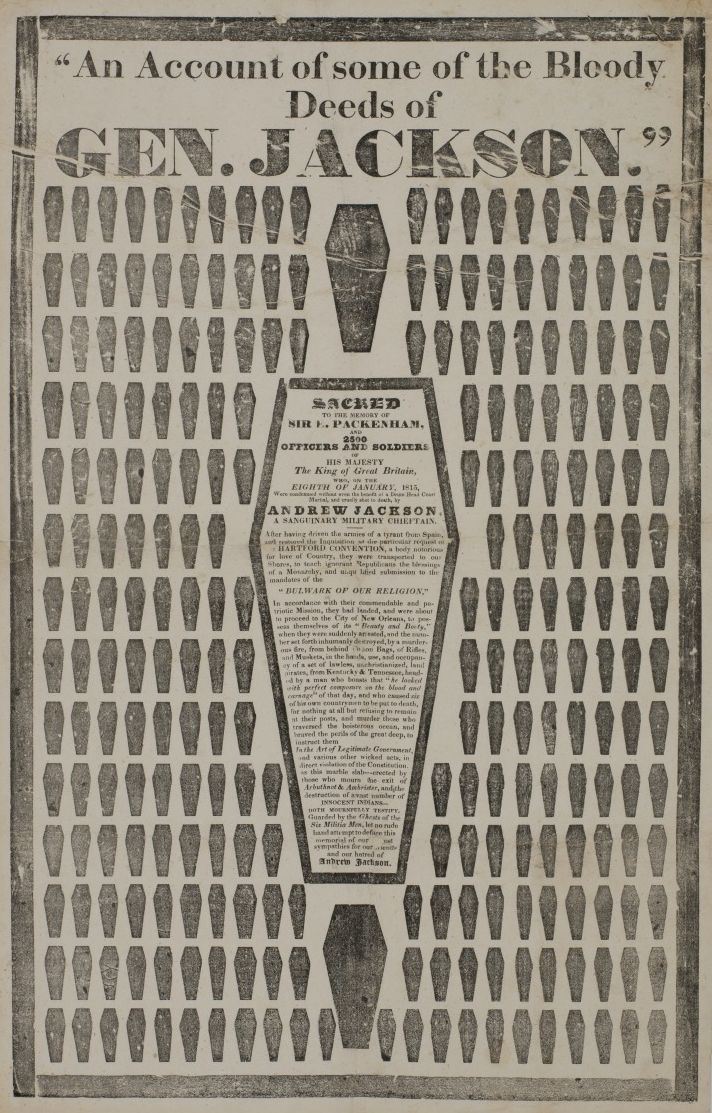

An Account of Some of the Bloody Deeds of Gen. Jackson

1828; letterpress broadside with woodcut

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2001-68-L.27

This unusual variant appears to be a British parody of other coffin broadsides: 184 black coffins of varying sizes surround a central coffin-shaped cartouche with a text lamenting the loss of General Edward Pakenham and other British soldiers who had come to New Orleans in 1815 to teach Americans "the blessings of a Monarchy."

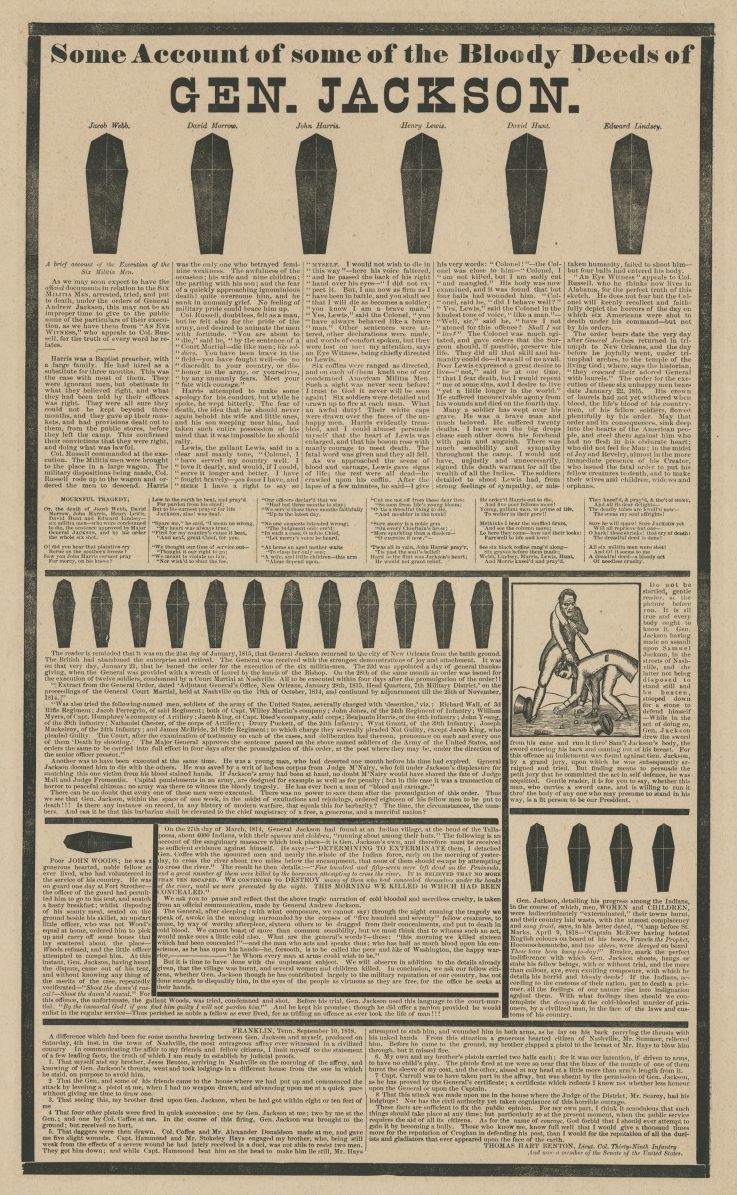

Some Account of Some of the Bloody Deeds of Gen. Jackson

1828; letterpress broadside with woodcut

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2001-68-L.29

Individual coffin broadsides varied in their details, but most featured the trappings of death announcements, including woodcut coffins and mourning borders. In addition to descriptions of the executed Tennessee militiamen, this example includes a caricature of Jackson caning another man, an account portraying the Battle of Horseshoe Bend as a massacre of an Indian village, and a letter describing a brawl between Jackson and others in Nashville.