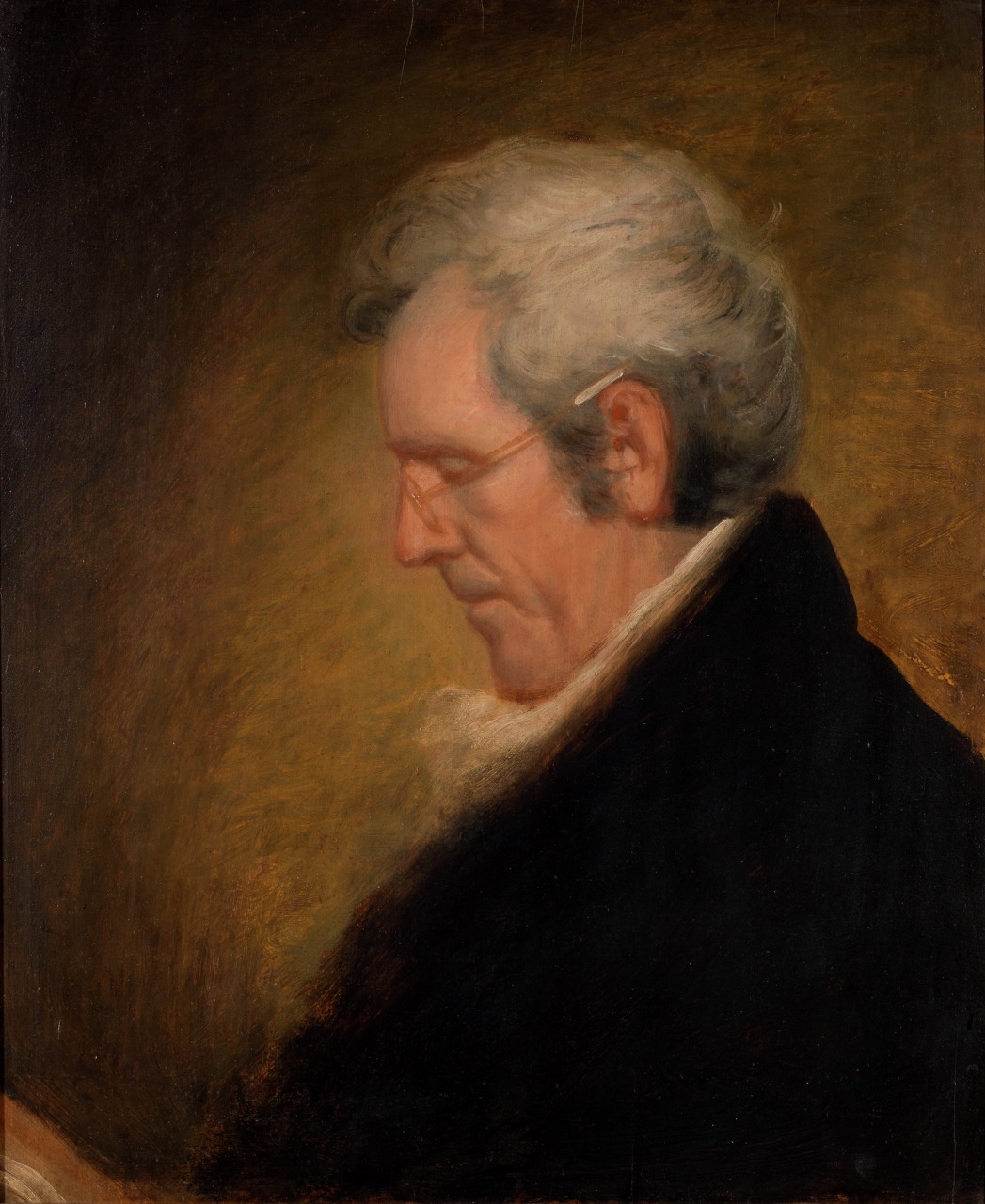

Some artistic representations of Jackson made between 1822 and 1827 mark his transition from military commander to civilian statesman, though he was still very much the Hero of New Orleans. In 1821, a few years after the First Seminole War (1817–18), Jackson resigned his commission as a major general and briefly served as the governor of Florida, newly acquired from Spain. Soon after his return to Tennessee, the legislature nominated him as a candidate for the 1824 presidential election.

The 1824 race in Louisiana was notable for the creative means used by Jackson’s supporters to tilt the odds away from Henry Clay, who was predicted to carry the state. While one would expect the Hero of New Orleans to be the favored candidate, many French-speaking Louisianans harbored hard feelings over Jackson’s heavy-handedness during the crisis of 1814–15. Jackson’s supporters used strategically timed horse races and other diversions to distract and delay pro-Clay delegates from reaching the legislative session in New Orleans, where the state’s electors would be chosen. Several pro-Clay legislators fell to temptation and failed to appear, thus splitting Louisiana’s electoral votes between Jackson and John Quincy Adams, and possibly costing Clay the presidency.

Jackson went on to win the popular vote in the national election, but without the necessary margin to enable him to take office. Aghast that Jackson might win, Henry Clay wrote a letter that was widely published in newspapers, expressing disbelief “that killing 2500 Englishmen at N. Orleans qualifies for the various, difficult and complicated duties of the Chief Magistracy.” In the end, the US House of Representatives awarded the presidency to John Quincy Adams, who chose Henry Clay as his secretary of state, provoking cries of “Bargains and Corruption” among Jackson’s supporters.

Andrew Jackson

ca. 1822; oil on wood panel

attributed to John Wesley Jarvis, painter

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1974.78

After Jackson's retirement from the military in 1821 and before his 1824 presidential campaign, images of Jackson in civilian attire began to show his transition from soldier to statesman.

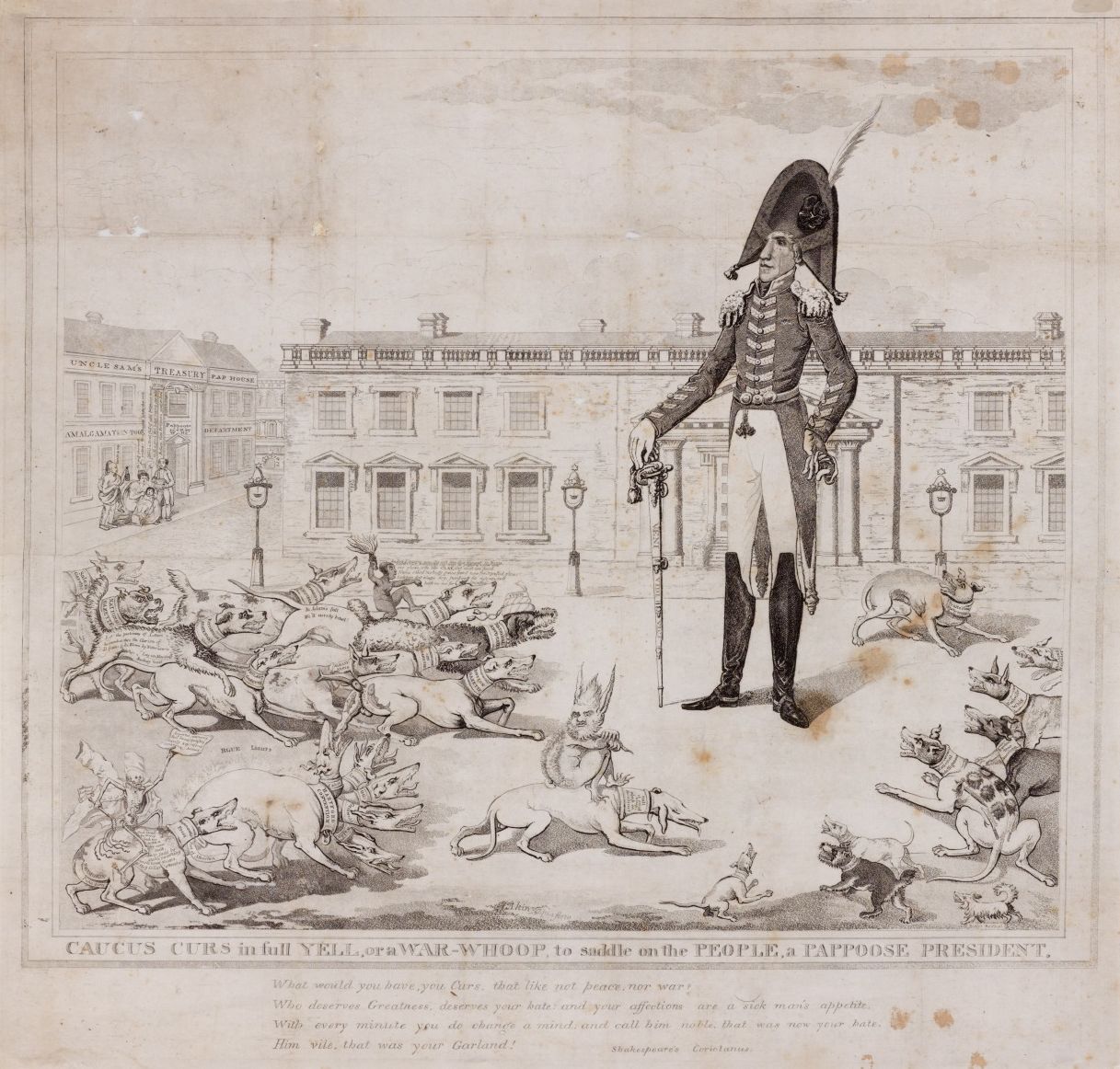

Caucus Curs in Full Yell, or a War-Whoop, to Saddle on the People, a Pappoose President

1824; aquatint engraving

by James Akin, engraver

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1975.78

The South Carolina-born artist James Akin (ca. 1773–1846) was a Philadelphia engraver, painter, and caricaturist. Here Akin denounces the press's treatment of Andrew Jackson during the 1824 presidential campaign and lampoons the politics of the caucus system of nominating candidates for public office.

Ballot of the electors for the State of Louisiana in the presidential election of 1824

December 1, 1824; manuscript document

by William Noll, James H. Shepherd, Pierre R. LaCoste, Jean Baptiste Plauché, and Sebastian Hiriart, signers

The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 469, 84-24-L.1

This official letter from Louisiana's electors to the US Senate splits the state's five electoral votes in the 1824 election between presidential candidates Andrew Jackson and John Quincy Adams. Jackson won the popular vote in most states but fell short of the majority needed for a decisive victory. The US House of Representatives decided the election in favor of Adams, outraging Jackson's supporters.

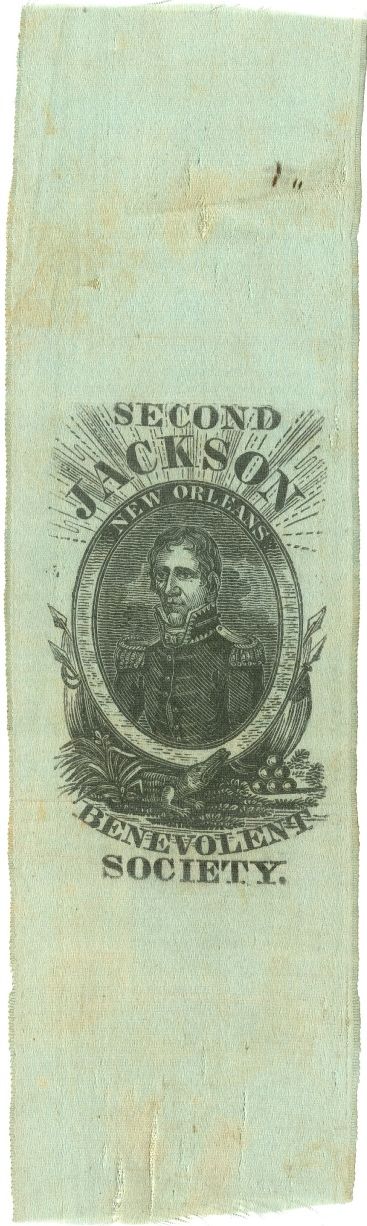

Second Jackson Benevolent Society ribbon

between 1815 and 1830; engraving on silk

The Historic New Orleans Collection, acquisition made possible in part by William C. Cook, MSS 557, 2014.0249.4

Portrayals of Andrew Jackson as a champion of the common man appeared through the 1824 election campaign. His image was used to promote benevolent societies and local Democratic Party committees across the country.

Plain Reasons of a Plain Man: For Preferring Gen. Jackson to Mr. Adams, as President of the United States

by Robert Goodloe Harper, author

Baltimore: Benjamin Edes, 1825

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 59-77-L.14