The Greenback Revolution and the Creation of a Unified National Currency

While the Confederacy began printing money at breakneck speed as early as March 1861, the United States struggled to devise its own system for financing the war. Because the Constitution explicitly authorized only the minting of hard currency rather than paper money, the US first relied on short-term loans from private banks and income derived from customs duties, taxation, and the sales of bonds and public lands to underwrite costs. None of these income streams, however, allowed the government to surmount the obstacle posed by individuals and banks—fearful of their financial futures—hoarding gold and silver specie.

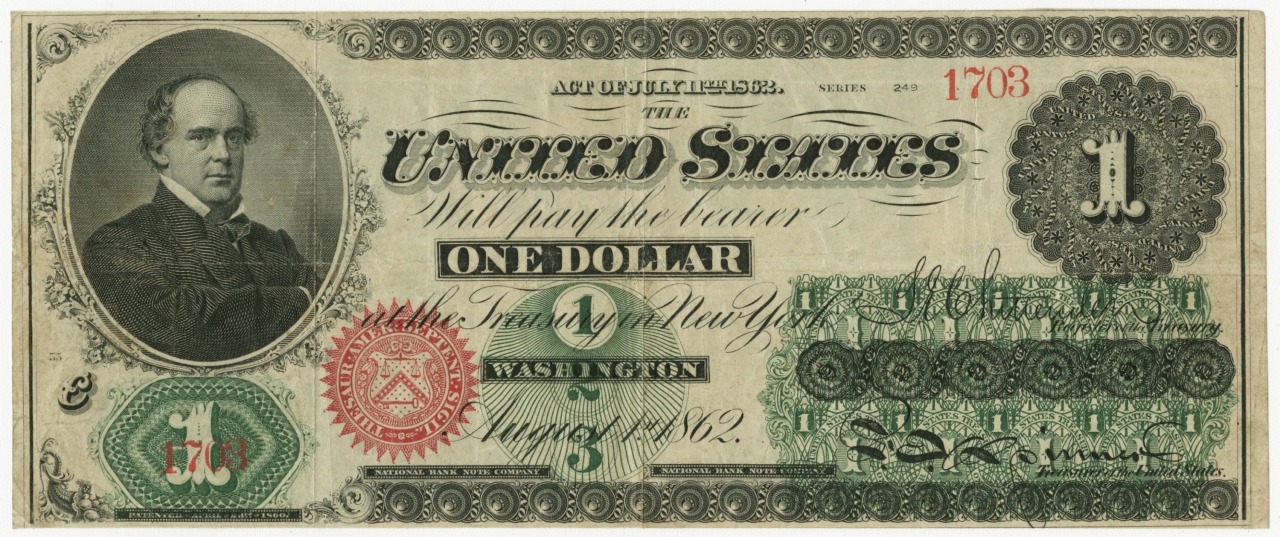

Like the Confederacy, the US government turned to paper money. The first federal banknotes, made possible by an act of Congress, appeared the summer of 1861. These notes, known as Demand Notes, circulated throughout the Union and were officially declared legal tender with the passage of the Legal Tender Act on February 25, 1862. The Legal Tender Act ushered in a new era in American banking. Under the act, paper money equaled the value of gold and silver specie and was to be treated as a universal currency accepted as payment for all debts, regardless of when they were incurred. To avoid further specie hoarding and in recognition of the Treasury’s own specie shortage, the notes could not be redeemed for coin. The act also authorized the issuance of a new type of note, Legal Tender or United States Notes. These green-backed notes appeared in denominations of $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100, $500, and $1,000 and were first issued between March of 1862 and March of 1863.

The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 further strengthened federal authority by bringing all banking activities under federal jurisdiction. The acts also prohibited nonfederal entities from issuing coins, and perhaps most importantly, at least in terms of the creation of a national currency, they made the issuance of banknotes by nonfederal entities subject to taxation, which led the vast majority of banks to cease printing paper alternatives. By 1870 federally issued notes reigned supreme throughout the newly reconciled United States.

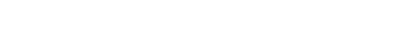

Bank of Louisiana ten-dollar note

June 14, 1862; engraving

by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch, and Edson, printer (New York or New Orleans)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of St. Mary’s Dominican College, 1984.205.182

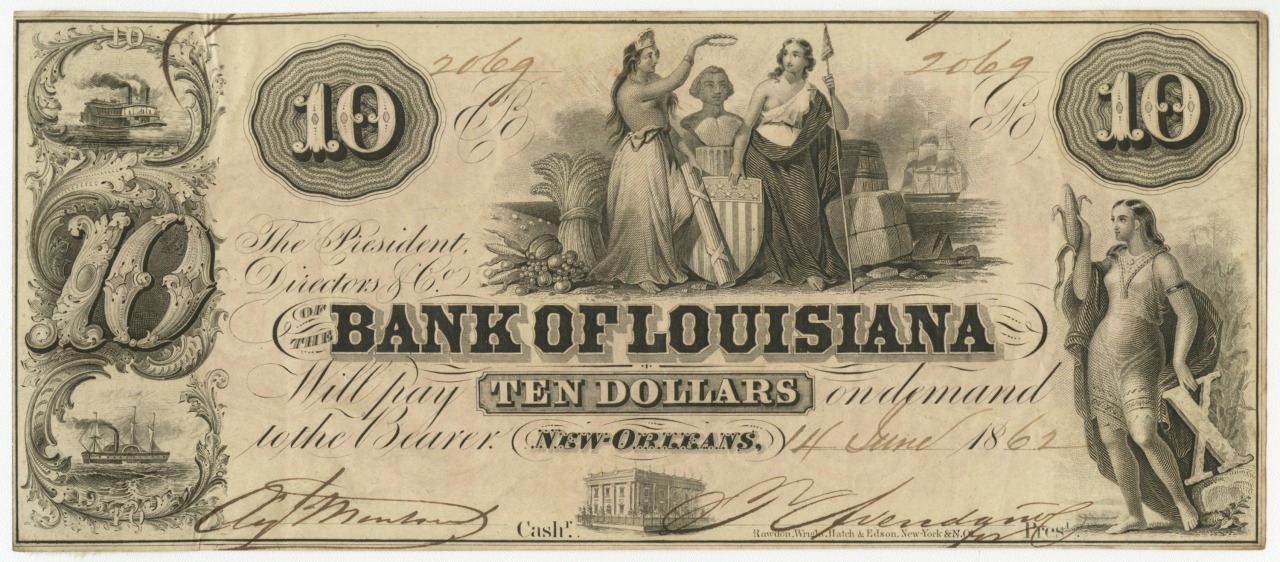

Bank of Louisiana fifty-dollar note

June 14, 1862; engraving

by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch, and Edson, printer (New York or New Orleans)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1974.25.22.39

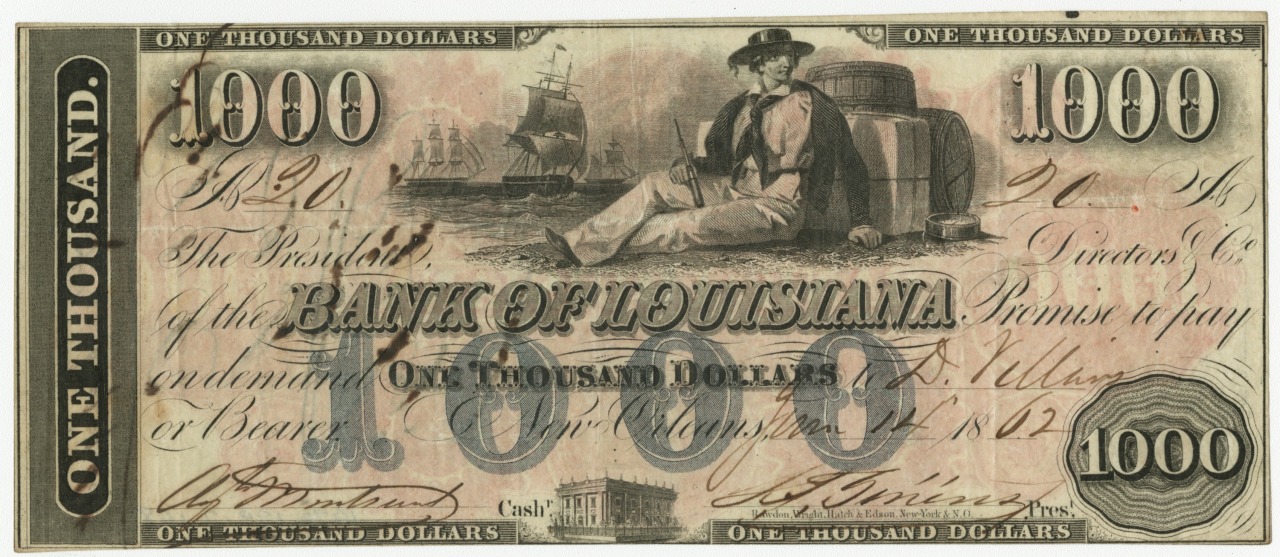

Bank of Louisiana one-hundred-dollar note

June 14, 1862; engraving

by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch, and Edson, printer (New York or New Orleans)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Mrs. Alfred Grima, 1976.129.2.57

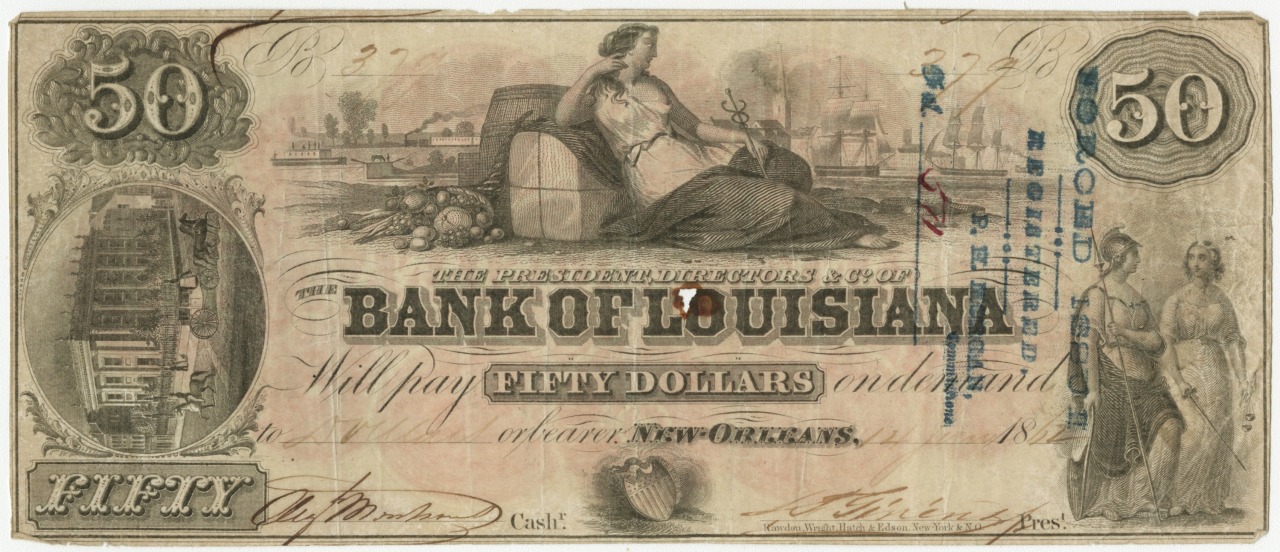

Bank of Louisiana one-thousand-dollar note

June 14, 1862; engraving

by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch, and Edson, printer (New York or New Orleans)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Mrs. Alfred Grima, 1976.129.2.108

United States of America one-dollar legal tender note

August 1, 1862; engraving

by National Bank Note Company, printer (New York)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2016.0021.2

United States of America twenty-five-cent note

1863; engraving

by National Bank Note Company, printer (New York)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1974.25.22.65

“The Federal Union / It Must Be Preserved” Union Civil War token

1863; stamped copper

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2000.59

United States of America ten-cent note

between July 14, 1869, and February 16, 1875; engraving

by American Bank Note Company, printer (New York)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1974.25.22.62

United States of America fifteen-cent note

between July 14, 1869, and February 16, 1875; engraving

by National Bank Note Company, printer (New York)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1974.25.22.64