Money and Why There Was Never Enough in French Colonial Louisiana

“We cannot, Gentlemen, refrain from calling your attention to the sad condition of our treasury. It has been without one sou for some time.”

––Louisiana Governor Étienne Périer and Director-General Jacques de La Chaise,

to the directors of the Company of the Indies, April 22, 1727

Louisiana suffered from an acute lack of specie, or coin money, throughout the French colonial period (1699–1763). Specie shipments from France were nearly nonexistent, and copper sous created in 1721 and 1722 especially for use in France’s North American and Caribbean colonies were prone to violent fluctuations in value.

Louisiana was not the only colony subject to specie shortages. Much of North and South America’s mineral wealth was controlled by the Spanish, whose mining operations in Peru, Bolivia, and Mexico produced the majority of gold and silver minted prior to the nineteenth century. Spain’s domination of hard-money markets meant that the most commonly circulated currency throughout the Americas was Spanish, with a colony’s access to coinage frequently dependent on illicit intercolonial trade.

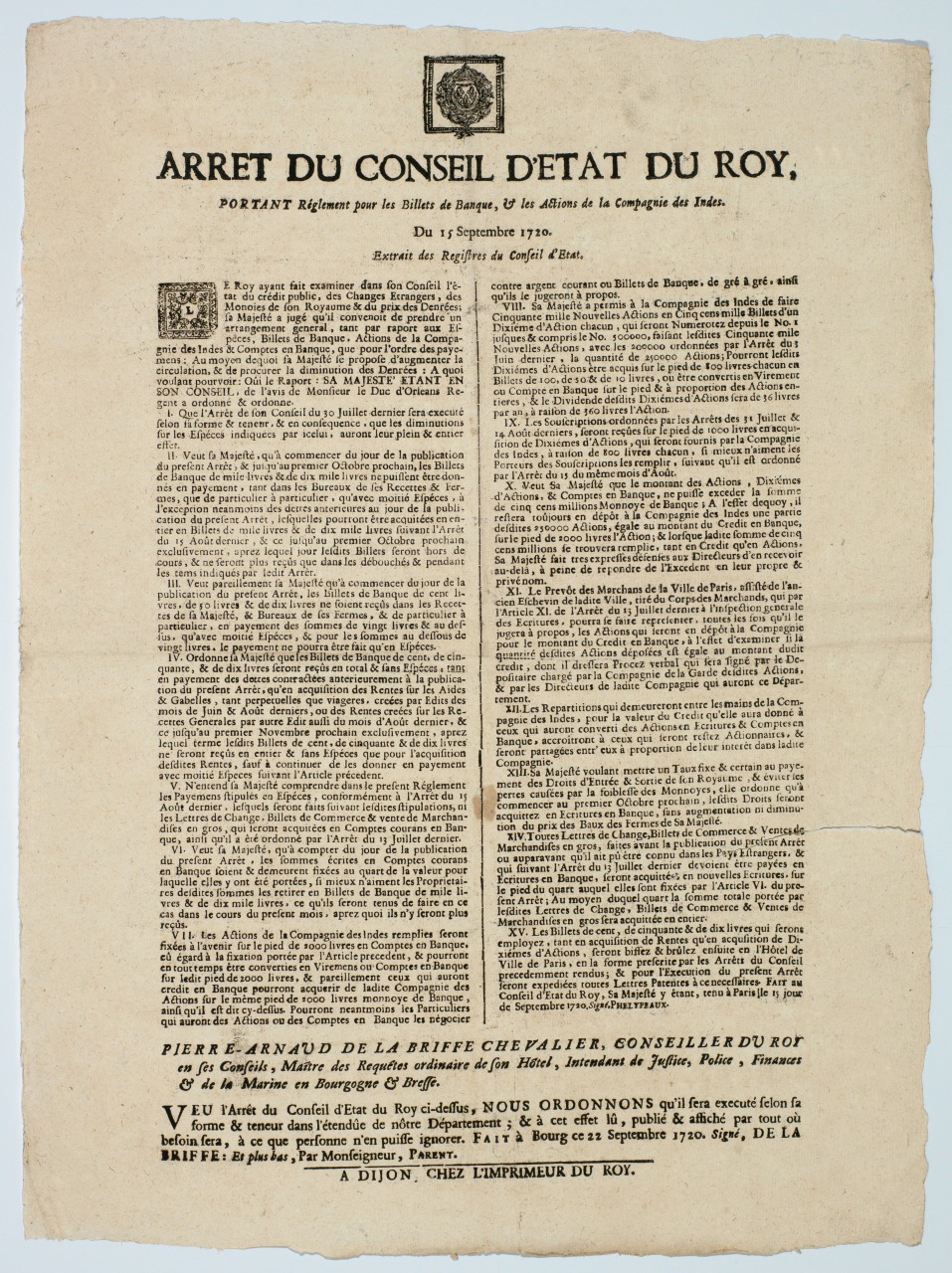

Arret du Conseil d’Etat du roy, portant réglement pour les billets de banque, et les actions de la Compagnie des Indes (Warrant of the king’s council on the regulation of banknotes and shares in the Company of the Indies)

Dijon: l’imprimeur du roy, September 15, 1720

The Historic New Orleans Collection, acquisition made possible in part by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 2010.0158.5

Banque Royale de France one-hundred-livre note

August 1, 1719; engraving with manuscript additions

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2001-47-L

Banque Royale de France fifty-livre note

September 2, 1720; letterpress printing with manuscript additions

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2000-97-LThe earliest banknotes in this exhibition may seem at first glance peripheral to banking in America, but their circulation by France’s Banque Royale between 1719 and the fall of 1720 helped fuel a speculative fever in the purchase of lands in the Louisiana colony. French investors used these notes—the first national paper money ever used in Europe—to purchase shares in the French Company of the Indies, a company whose theoretical worth was largely premised on promises of Louisiana’s riches.

In late 1720, when word reached France that Louisiana’s prospects had been grossly overblown, investors rushed to cash in their remaining notes, demanding specie in exchange. What followed was a massive economic crash known as the Mississippi Bubble.

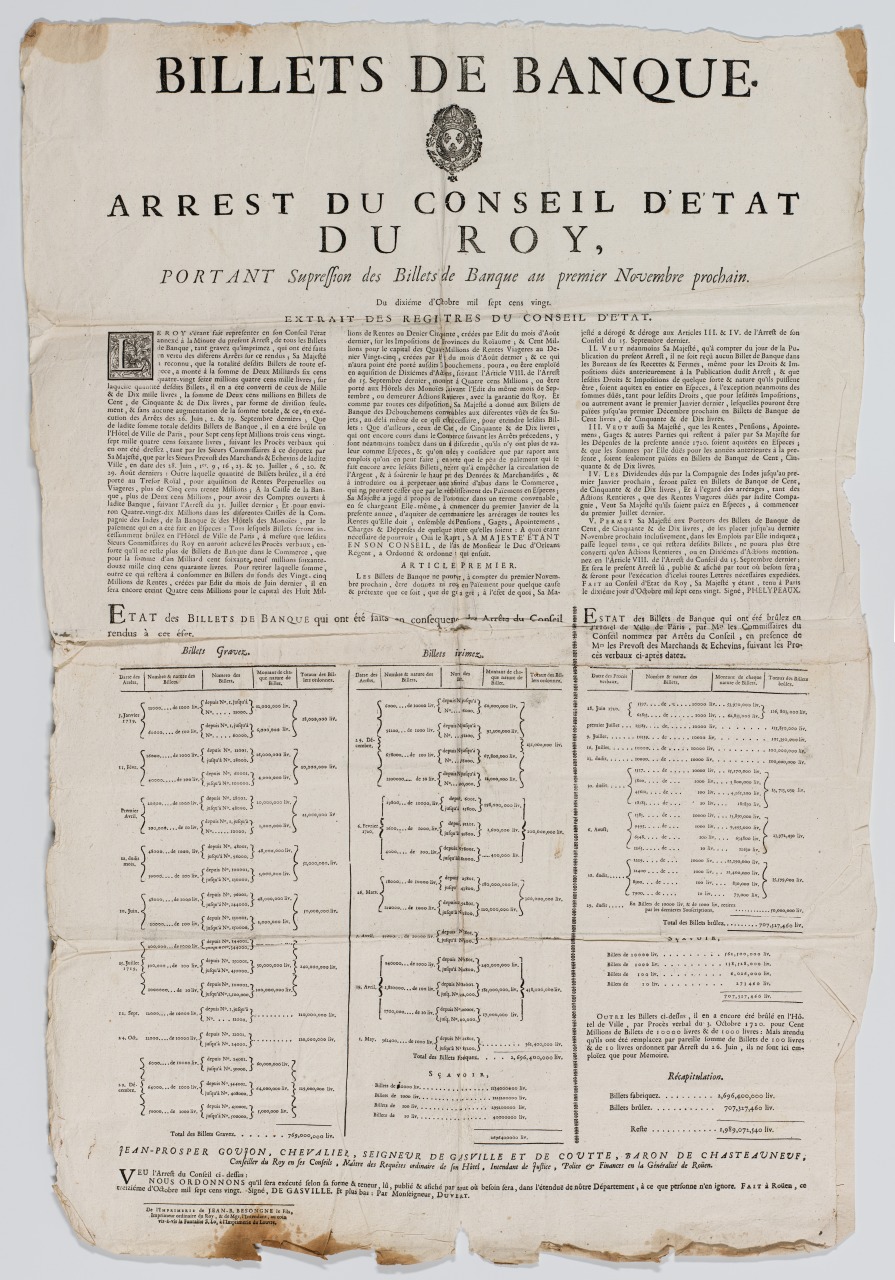

Arrest du Conseil d’Etat du roy, portant suppression des billets de banque au premier novembre prochain (Warrant of the king’s council on the suppression of banknotes beginning November 1)

Paris: Imprimerie de Jean-Baptiste Besongne le fils, October 10, 1720

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2016.0069.2

French sou

1722; copper

minted in La Rochelle, France

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1978.137

Spanish half real, or picayune

1747; silver

minted in Mexico City, Mexico

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of H. Waller Fowler Jr., 1997.21.3

Clipped Spanish one real

before 1788; silver

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2013.0328.1.5

Bill of exchange worth 200 gourdes, or piastres

April 2, 1803

The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 579.3.35, 2008.0100.58This bill of exchange worth 200 gourdes (a French Caribbean term sometimes used interchangeably with piastres or dollars) gives modern viewers a glimpse of the credit economy prior to the widespread use of printed banknotes. Drawn up in New Orleans and issued by Charles Vauquelin, the bill was originally intended as payment of account from Vauquelin to Monsieurs Lauthois and Pitot. Its usefulness did not stop there, however, as the bill continued to circulate, holding its value as it passed through the hands of New Orleans merchant Jean François Merieult (whose house at 533 Royal Street is part of The Historic New Orleans Collection) and Delarbre and Company.